This article follows up on the one published on July 7th 2021, and aims to highlight the presence of First Nation and Black slaves within the English and French populations of the Laurentian valley.

Source : Création Bernard Duchesne

James McGill is one of the most famous cases of a slave owning member of the elite. This trader, who at some point was magistrate and member of the council which constituted the government of Montreal, will have at least five slaves (McGill, 2021). One of these slaves was a Black girl named Marie-Louise:

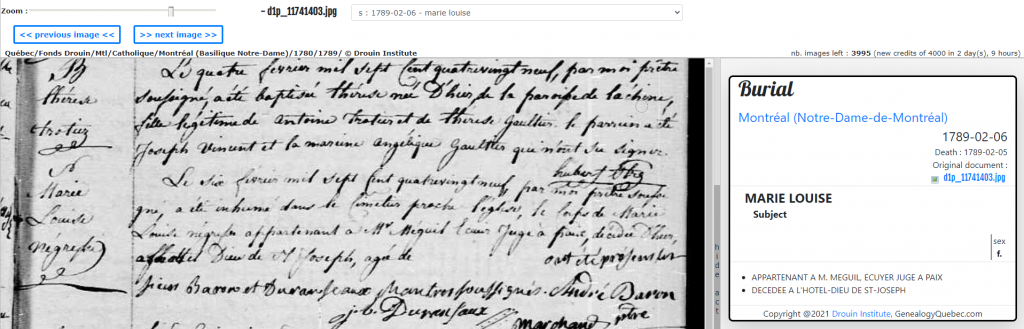

” On the sixth of February one thousand seven hundred and eighty-nine, by me, the undersigned priest was buried in the cemetery near the church, the body of Marie Louise [black] belonging to Mr. McGuil squire, justice of the Peace, deceased yesterday, at the Hôtel Dieu de St-Joseph, aged ____, the undersigned Sieur Baron and Duransaux Montres were present. André Baron “

« Le six février mil sept cent quatrevingt neuf, par moi prêtre soussigné, a été inhumé dans le cimetière proche de l’église, le corps de Marie Louise [Noire]appartenant a Mr Mcguil Ecuier Juge à paix, décédée d’hier, a l’Hotel Dieu de St Joseph, âgée de ____ ont été présent les sieur Baron et Duransaux montres soussignés. André Baron [sic] »

Marie Louise’s burial record.

Source: Record 572200, LAFRANCE, GenealogyQuebec.com

There is a popular belief that the enslaved people of ancient Quebec mostly belonged to nobles. But as it turns out, only 38% of slaves lived in upper class households according to the information available today. 31% were enslaved by merchants, and another 31% by farmers, labourers, voyageurs, blacksmiths, bakers, and other members of the lower class (Dupuis, 2020).

In this last stratum of the population, we find François Campeau, a blacksmith and second-generation slave-owner, who enslaved at least two First Nation girls: Marguerite, who died at 15 years old, and an unnamed young girl who died at 13 years old.

” The year one thousand seven hundred and thirty-seven on the eighth of January, I the undersigned Jean Bouffandeau, priest of the seminar of st-joseph have buried in the cemetery of the poor the body of Marguerite [First nation] aged about fifteen (?) belonging to Francois Campeau blacksmith who died yesterday in the communion of the said Roman Church, were present the same Campeau and Simon Mongino “

« Lan mil sept cent trente sept le huit de janvier, je soussigné Jean Bouffandeau pretre du seminaire de (?)ay inhumé dans le cimetière des pauvres le corps de Marguerite sauvagesse âgée d’environ quinze ans ayant appartenant a Francois Campau forgeron décédé hier en la communion de laditte Église Romaine ont été présent led. Campeau et Simon Mongino [sic] »

Marguerite’s burial record.

Source: Record 151707, LAFRANCE, GenealogyQuebec.com

What tasks were asked of Marguerite? Why was she living in this household? These questions are difficult to answer, but the biographical archives allow us to speculate on her living conditions.

François Campeau, married in 1698 to Marie-Madeleine Brossard, will have a total of 14 children. Marie-Madeleine died in 1729, which could correspond with the year of Marguerite’s purchase. We do not know the date of Marguerite’s arrival in New France, but we do know that Native slaves arrived on the territory at a young age (Trudel, 2004).

If so, she would have joined the Campeau family around the age of eight and the household would have included François Campeau, six of his sons as well as three of his daughters, all single and aged between 11 and 30. It would therefore be entirely possible that Marguerite performed domestic chores in the household to help with the needs of the family following the death of Marie-Madeleine.

It turns out that the Campeau will become a multigenerational slave owning family. François Campeau’s father, Étienne Campeau, is the first in a line of five generations of slave owners. Without being very wealthy and coming from modest professions such as mason, carpenter and blacksmith, this family will nonetheless build a slave network that expanded from Montreal to Detroit.

The Campeau family is not an isolated case. Biographical research has allowed us to learn more about the various slave owning families, such as the Demers, Boyer, Hervieux and Parent families, who will own slaves for at least three generations. This is in addition to the rich slave owning families: the Baby, the Tarieu de Lapérade, the Lemoyne de Longueil, the Lacorne Saint-Luc and the Fleury D’eschambault, to name a few.

Commemorative plaque of Olivier Le Jeune, first African slave and resident of New France

We even find traces of slaves in the families of the last two Prime Ministers of Quebec: Guillaume Couillard (direct ancestor of Philippe Couillard), owner of Olivier Le Jeune, the first known black slave in Quebec territory, and Charles Legault Deslauriers senior (direct ancestor of François Legault), owner of a young native Panisse who died at 10:

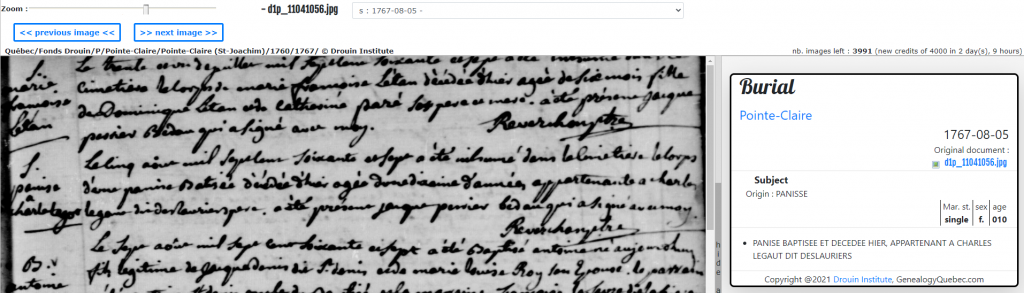

” The fifth of August one thousand seven hundred and sixty-seven were buried in the cemetery the body of a baptized panise who died yesterday, aged about ten, belonging to Charles Legault dit Deslauriers senior. Was present Jacques Perrier said who signed with me.”

« Le cinq aout mil septcent soixante et sept a été inhumé dans le cimetière le corps d’une panise Baptisée décédée d’hier âgée d’une dixaine d’années appartenante a Charles Legault dit deslauriers pere. A été présent jacques perrier led au qui a signé avec moy [sic] »

Burial record of a Panise owned by Charles Legault.

Source: Record 368509, LAFRANCE, GenealogyQuebec.com

In conclusion, I hope to have demonstrated that slave owners were not necessarily well off and came from various backgrounds and classes. In New France, we find Black and First Nation slaves in several families and institutions, in all social strata, as well as in all regions of the Laurentian Valley, from Gaspésie to Detroit.

Cathie-Anne Dupuis

MSc. Demography,

Doctoral candidate in history

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boulle, Pierre H. 2007. Race et esclavage dans la France de l’Ancien Régime. Paris, France: Perrin.

Peabody, Sue. 1996. « There are no slaves in France » : the political culture of race and slavery in the Ancien Régime. New York ; Oxford: Oxford University Press.