This post is also available in: Français

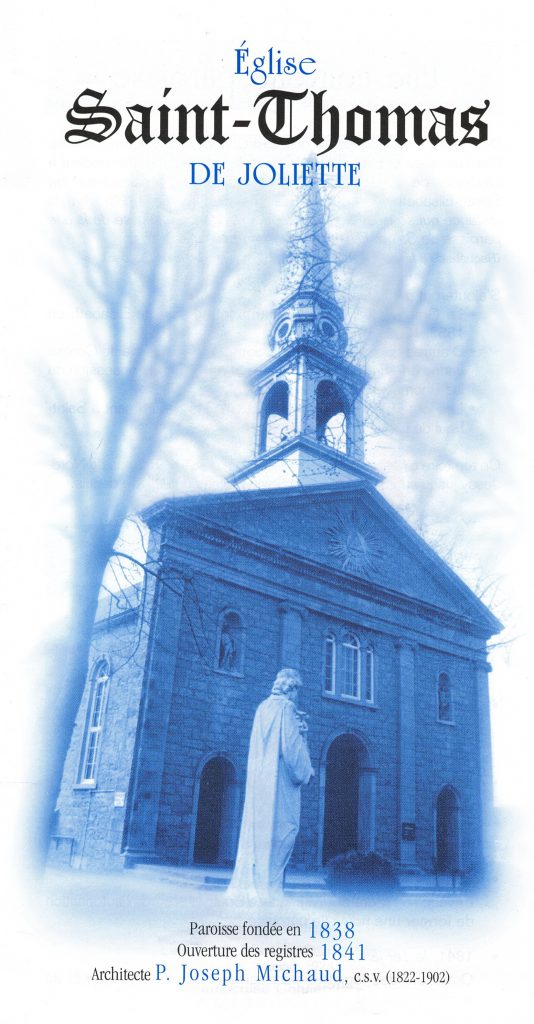

In genealogical research, locations often play a very important role : they can help us confirm a person’s identity or guide our research when looking for an ancestor. Even if their role is not central to our investigation, from the moment we consult modern sources such as civil records or a nominative census, we will necessarily encounter a variety of toponyms (Jetté, 1991 : 89) – cities, parishes or even street names!

Source: Drouin Institute’s Miscellaneous Collections (Fonds Pierre-Colpron), GenealogyQuebec.com

Thereby, you may have noticed that Quebec’s toponyms are far from parity. We estimate that women represent less than 10% of Quebec anthroponymic toponymy. To phrase it differently, for each place named after a woman, there are 10 others named after a man (Beaudoin and Martin, 2019 : 1).

Faced with this observation, a movement for toponymic parity was created. Sarah Beaudoin and Gabriel Martin are both involved in this cause : Beaudoin as a feminist activist and Martin as a linguist. They published a book about the subject : Femmes et toponymie, de l’occultation à la parité.

The book offers a surprisingly complete overview for its 125 pages. The authors first present a historical portrait of the movement for toponymic parity in Quebec, then address common myths. From the supposed low importance of working towards toponymic parity to the so-called insufficient number of prominent women in history, all arguments against resolutions aimed at achieving toponymic parity are examined.

Through the development of this argument, the authors discuss a variety of feminist concepts such as radical feminism and patriarchy. The book also demonstrates a sensibility towards different types of oppression (like racism and colonialism), particularly for indigenous issues. The cover is a tribute to An Antane Kapesh, an innu band leader and author of the well-known book Eukuan nin matshimanitu innu-iskueu – I am a damn savage. However, the use of the term “amerindian” a few times in the book is regrettable since it is now considered derogatory (Picard, 2018).

The book ends with a list of potential toponyms and a chart for toponymic parity, which serves as a concrete link between the demands of the movement and Quebec’s reality. It is also a good opportunity to discover women who have marked our history : among the 145 toponymic suggestions, 10 are the subject of a short presentation, more than half of which are racialized and/or indigenous women.

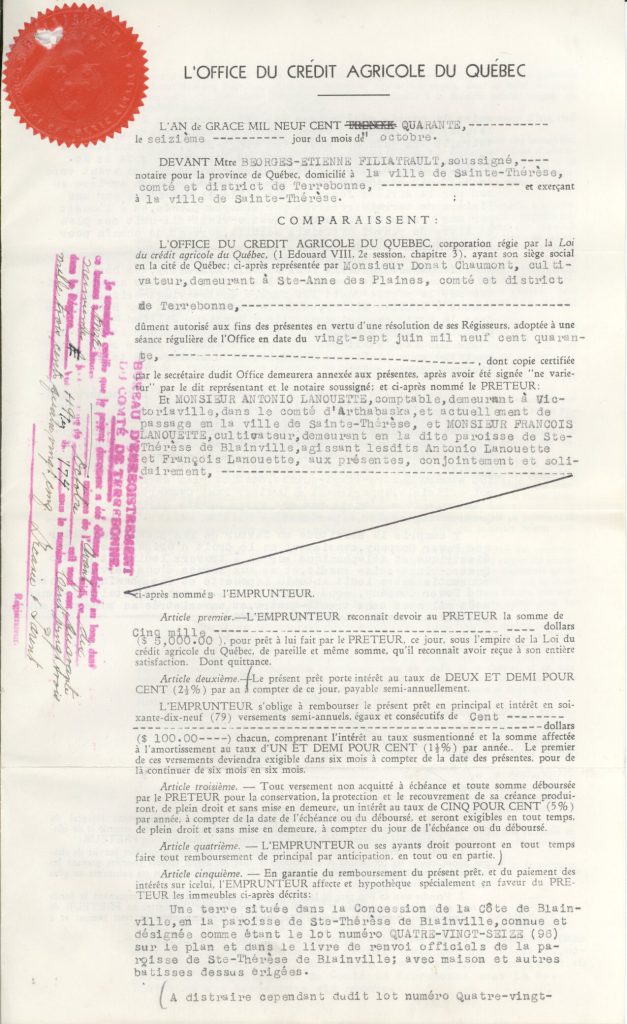

Source: Notarized documents tool, GenealogyQuebec.com

The book accomplishes the feat of remaining very accessible while addressing several issues in depth. Those who are not very familiar with feminism or toponymy will nonetheless understand, the book serving as a good introduction to these subjects. Those who have a deeper understanding of either feminism or toponymy will also find their read interesting : even after studying feminism in university, I learned quite a lot reading this book, finding ways to refine my feminist argument and discovering prominent women of our history.

All in all, it is an excellent book that will provide you with a different outlook, both in your genealogical research and in your everyday life.

Audrey Pepin

Reference list :

Jetté, René. (1991). Traité de Généalogie. Montreal : Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 716 p.

Beaudoin, Sarah et Martin, Gabriel (2019). Femmes et toponymie, de l’occultation à la parité. Sherbrooke : Les Éditions du Fleurdelysé, 125 p.

Picard, Ghislain (2018, September 26th). « Non, les Autochtones ne sont pas des Amérindiens ». HuffPost Québec. https://quebec.huffingtonpost.ca/ghislain-picard/autochtones-pas-amerindiens-terminologie-colonialisme_a_23541813/