Increasingly, we hear about family models that diverge from heterosexual and cisgender1 norms. The rights of LGBTQ+ individuals to form a family (and to access various methods allowing them to have children) are indeed recent, and the political events of the last few months demonstrate that these rights are still precarious. Certain groups, often associated with the far-right, seek to challenge the rights of queer2 individuals, especially those who are transgender (Massoud, 2023; Beaulieu-Kratchanov, 2023). These groups claim an international fight against the “homosexual agenda” and consider the very existence of queer individuals as ideological, stemming from “propaganda,” or even indoctrination, and depicting a “deterioration” of society (arguments that also exist, moreover, concerning homosexuality). In this context, it seemed essential to me to explore what genealogy could teach us about these realities – particularly how it could make them visible and help deconstruct marginalizing narratives.

Finding our LGBTQ+ ancestors

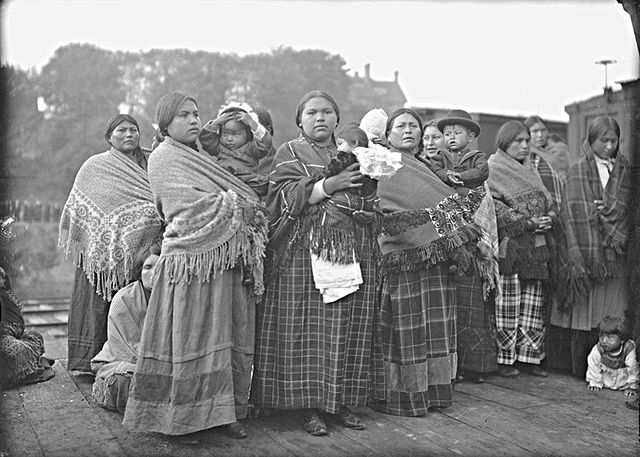

Some people sometimes feel that there are “more and more LGBTQ+ individuals.” This is purportedly an argument supporting the idea that queer identities result from indoctrination. In reality, this impression is created because people within the sexual and gender diversity spectrum increasingly feel less need to hide – however, there have always been queer individuals, and it’s highly likely that among your ancestors and mine, there were LGBTQ+ persons.

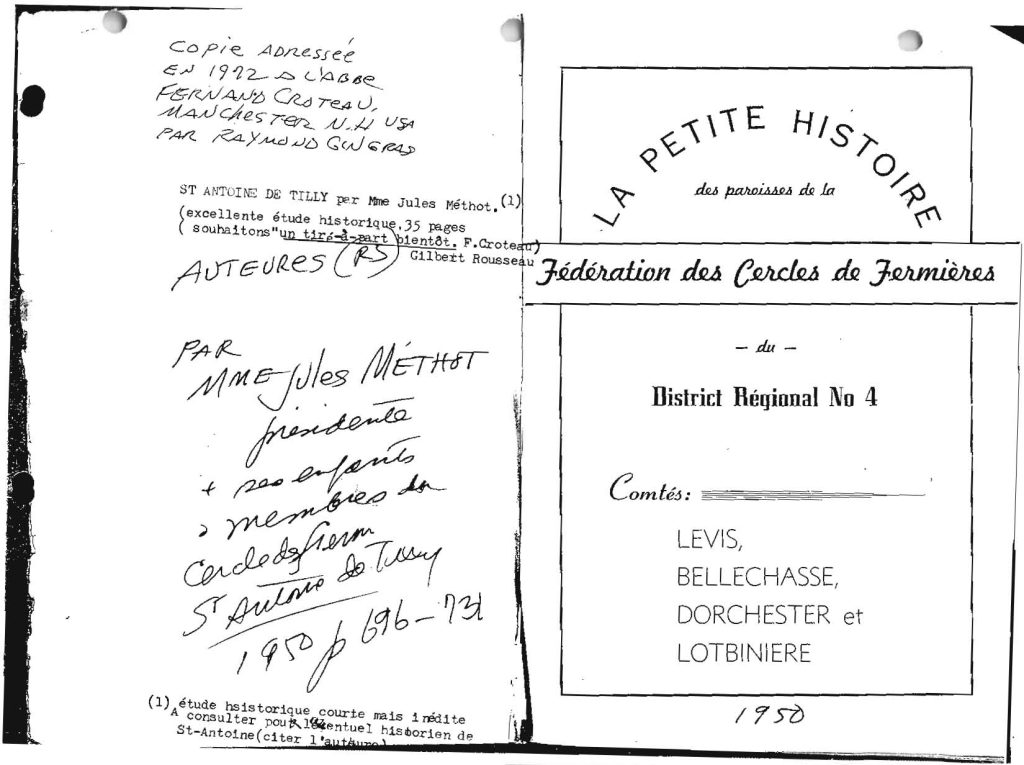

Identifying them can be challenging because they often had to live in secrecy. Nonetheless, it’s not impossible3. Of course, one can begin by looking into ancestors who did not marry (or who got divorced if it was legal), had few or no known romantic relationships, and did not have children. LGBTQ+ individuals also tended to choose professions where being single was not unusual, or even required – like teaching, the clergy, and the arts (Leclerc, 2023). Many also became self-employed or entrepreneurs because this way, if their identity was discovered, they couldn’t be dismissed (MacEntee, n.d.). Some of these professions also allowed for easy mobility and relocation if needed. These are not conclusive pieces of evidence, and there were LGBTQ+ individuals who did not fit these criteria, but they can be good initial clues!

Ideally, we would have access to our ancestors’ correspondence or journals. These documents can help us better understand their lives, including their gender identity and sexual attractions. Traces of LGBTQ+ ancestors can also be found in legal records and newspapers of the time: homosexuality was illegal in Canada until 1969. Therefore, homosexual individuals could be prosecuted, and traces of their trials can be found in such documents4. If they were in the military and their identity was discovered, they were likely to be discharged. When using these sources, remember to investigate the terms used at the time to describe gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, and transgender people – all these terms are relatively recent. Moreover, LGBTQ+ individuals often had to use codes to avoid being identified, which put them in danger.

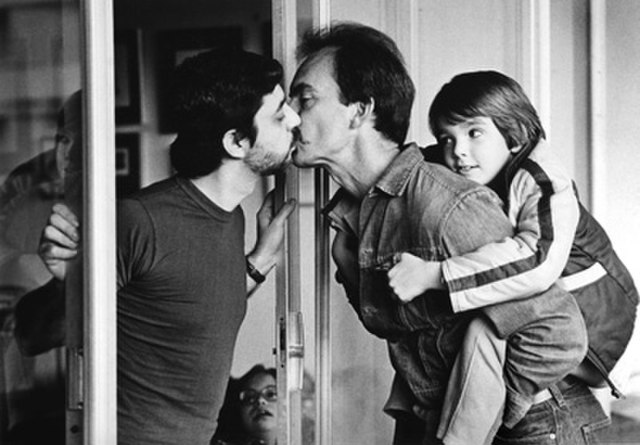

However, in the absence of indisputable evidence, additional clues can be sought. For instance, one can start by looking into the places where the person lived. Did they reside in a gay neighborhood? Were there places, private clubs, for example, that served as safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community at that time? Did they leave traces of the people who frequented these places? In census records, when a same-sex couple lived together, both partners often found ways to present themselves without revealing the nature of their relationship. Sometimes, it was simply left undefined, or defined in vague terms like a “friend,” or disguised under another label such as a housekeeper or tenant. Clues can also be found in records listing passengers of transportation companies, indicating that two same-gender individuals lived together.

Subsequently, one can look into our ancestors’ network of relationships. Often, LGBTQ+ individuals were rejected by their families due to the heavy prejudices of the time. When archives are found for all our ancestors except one, questions arise: it’s possible that an embarrassed family sought to erase the presence of an LGBTQ+ member by wiping out their presence as much as possible. If relations with the family were severed, it’s likely that our ancestors did not bequeath their material possessions to them. Hence, examining their wills can be insightful. Historian and genealogist Mary McKee (2022) notes that the “new support circles”, the chosen family of queer individuals, is often revealed in their wills by the individuals they chose to inherit their material possessions. Similarly, same-gender couples were sometimes buried together: if your ancestor is buried with a same-gender person who wasn’t part of their family, that could have been their partner. A person of the same gender might also be mentioned in their death certificate as a “long-time companion,” “close friend,” or even a roommate!

In short, to trace and identify our LGBTQ+ ancestors, we need to think outside the box! Sometimes, we need to look beyond the “traditional” sources typically used in genealogical research, consider absences as much as findings, and even consider that our ancestor might have used an alias in certain circles to avoid being exposed. Having a good understanding of the LGBTQ+ history of our country or region will guide us on where to search and what to focus on depending on the era in which our ancestor lived. Of course, in several cases, despite your efforts, confirmation of your ancestor’s queer identity might not be attainable – but you will still have good reasons to suspect it.

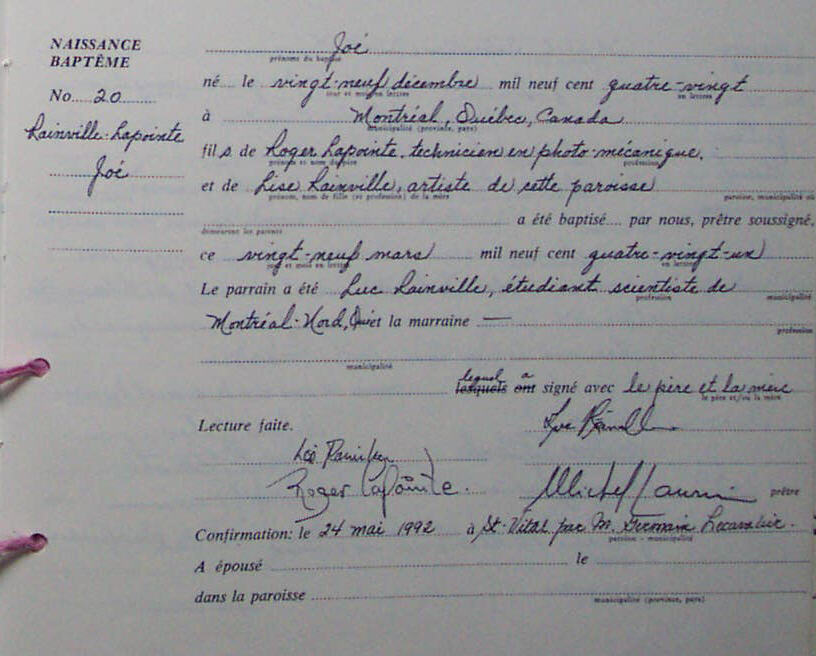

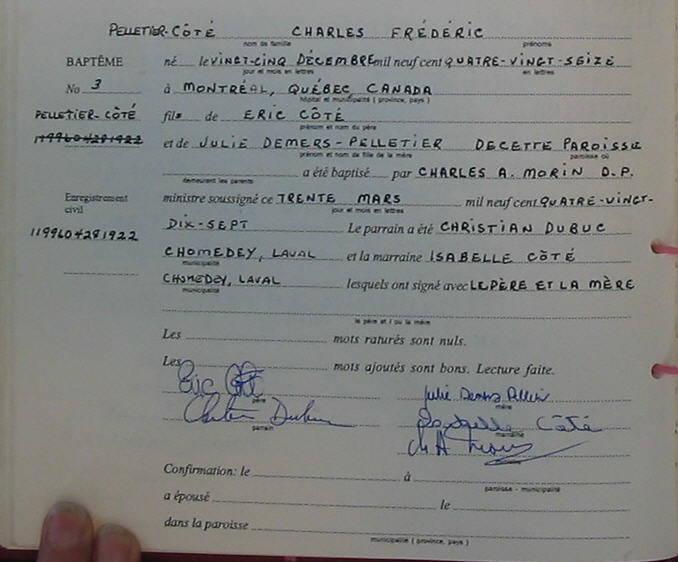

Representing non-conventional family models in our family trees today

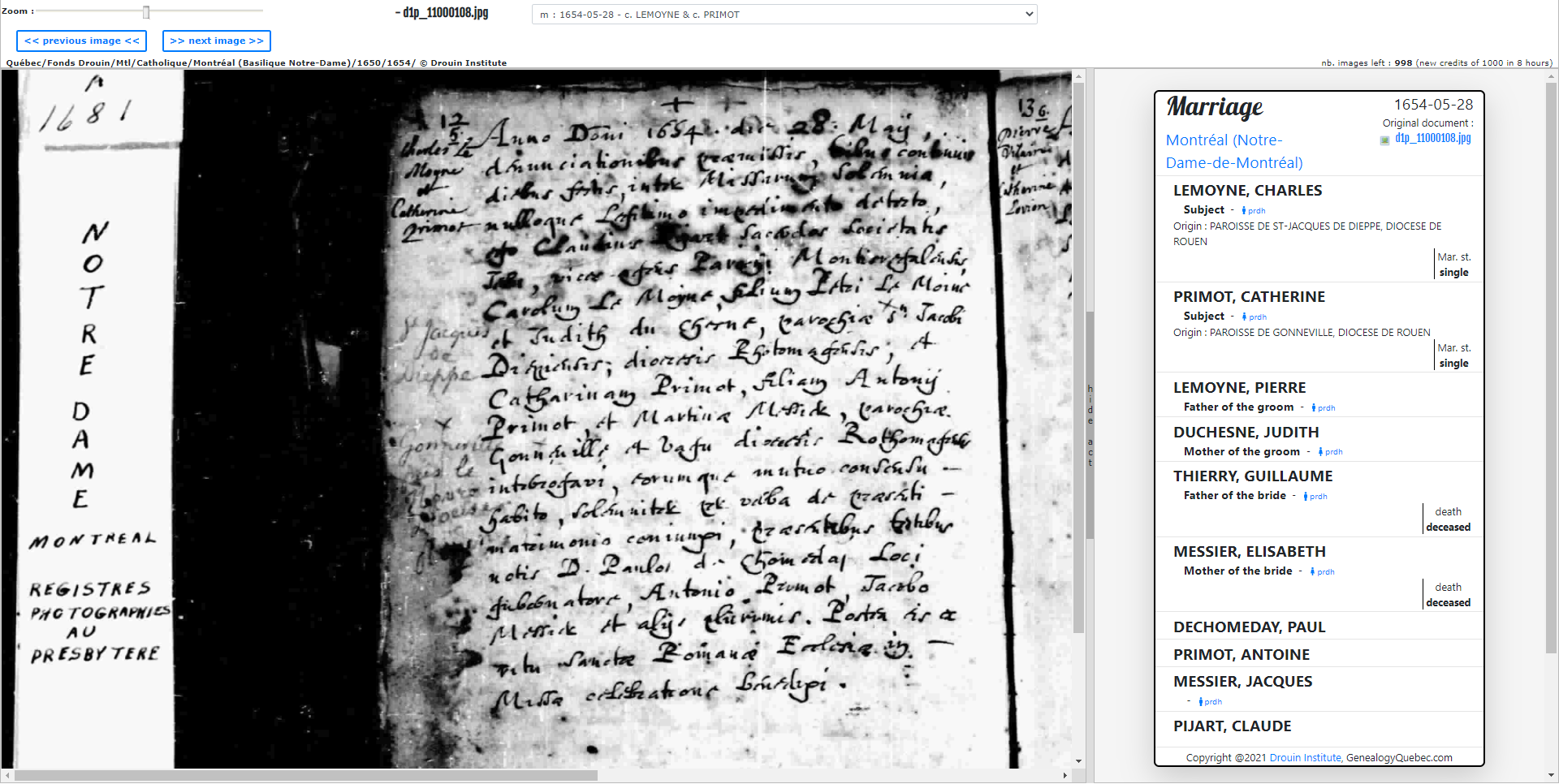

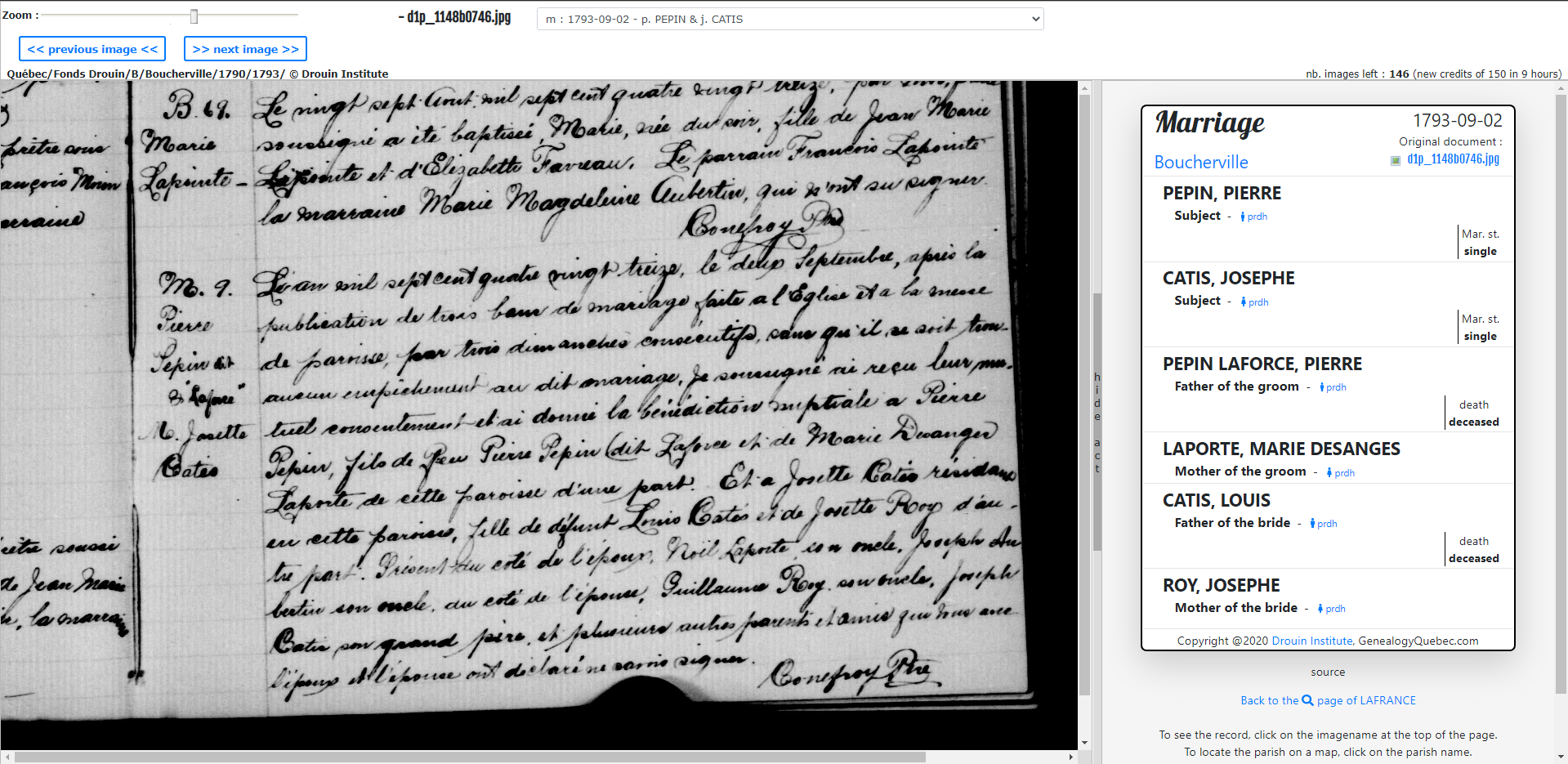

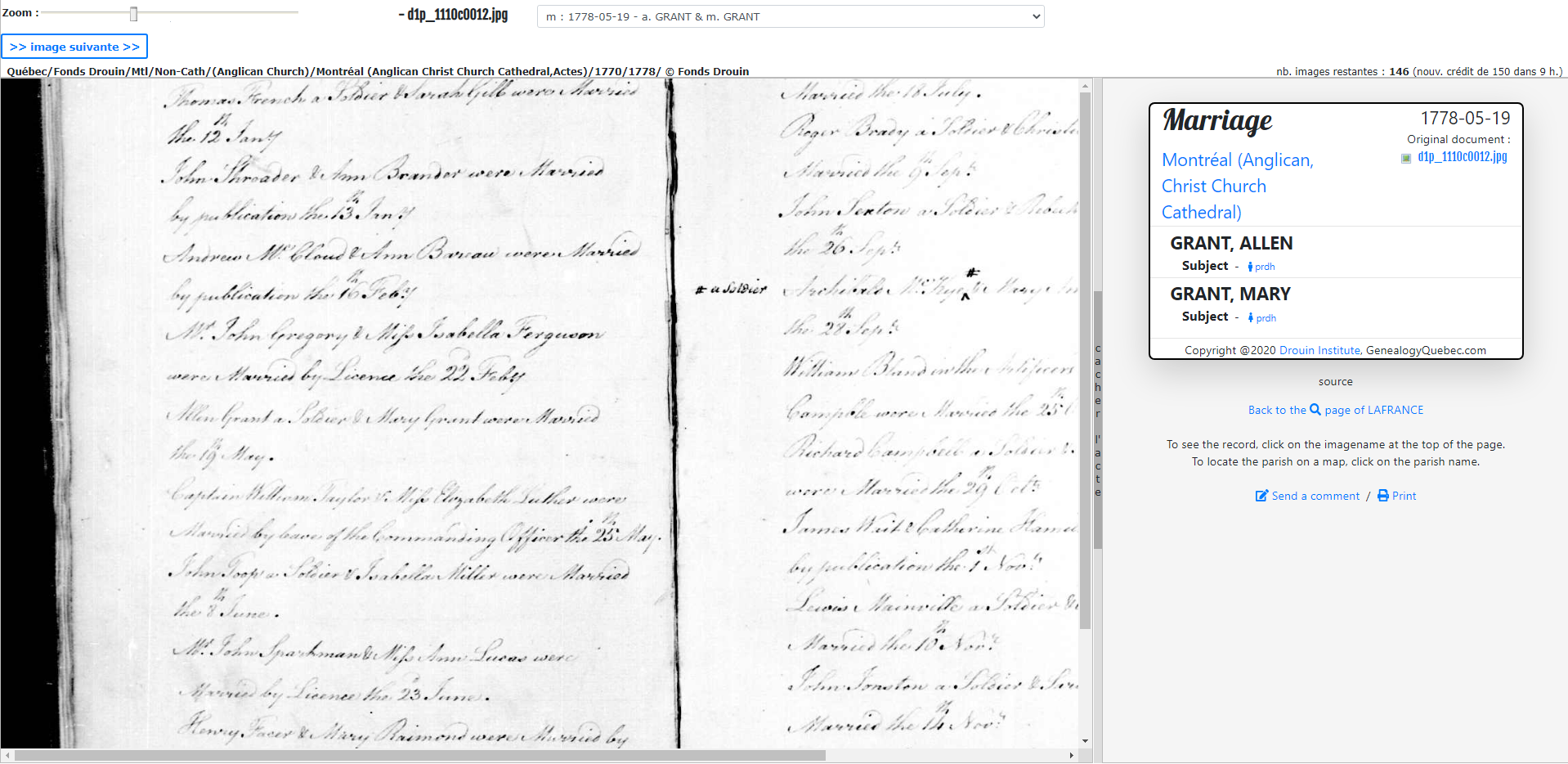

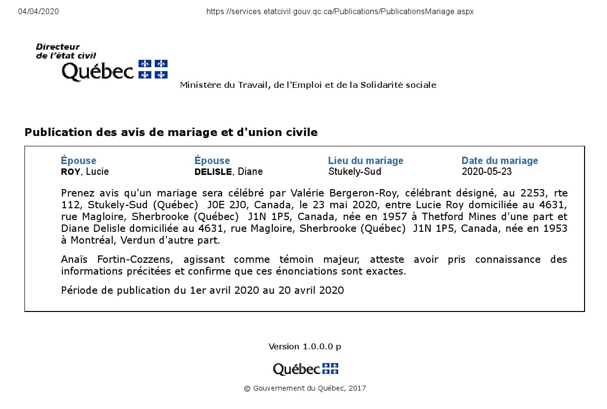

It is imperative that the various platforms used for building family trees include features that allow representation of unions between same-gender individuals, as well as individuals who do not identify with the gender assigned to them at birth5. Even today, this is not always the case – although it is on Genealogy Quebec in the section of marriages from the Directeur de l’état civil (DECQ)’s records and on other sites and software (see Koeven, 2018). Similarly, rules concerning photos that can be uploaded to these platforms should be inclusive: some sites have been criticized for prohibiting photos representing “cross-dressing” or “immodest” attire.

Let’s not forget that LGBTQ+ realities are not the only ones deviating from conventions and facing challenges in representation. It is crucial to adapt our genealogical tools to the realities of so-called “blended” families, where parents separate and then form new relationships, sometimes with individuals who already have children, families who adopt, families where there’s only one parent, by choice, as well as parents practicing ethical non-monogamy6. Again, a few sites and software allow this, but not all (see Waldemar, n.d.), and individuals sometimes have to resort to software not designed for genealogy to document these realities.

While it’s important to adapt our tools, it’s also crucial for laws governing unions and parenthood to continue evolving to recognize the entire diversity of family models! Many strides have been made in recognizing unions and children born out of wedlock, blended families, and the legalization of same-sex marriage (Magnan-St-Onge, 2020). However, the issue of polyamorous7 parents remains unresolved to this day. Lawyer and doctoral candidate Michaël Lessard documented that polyamorous individuals who fulfill a parental role may be excluded from decisions related to the custody, monitoring, and education of the child, regardless of the quality of their bond with them, and that privileges and economic and social assistance programs reserved for partners exclude polyamorous individuals, leaving them disadvantaged and therefore precarious (Magnan-St-Onge, 2020).

In conclusion, it seems essential to reflect on the reasons that drive us to reveal the LGBTQ+ (confirmed or presumed) identity of our ancestors. Thomas MacEntee (n.d) reminds us that disclosing one’s LGBTQ+ identity is a highly personal issue, and even today, not all individuals belonging to sexual and gender diversity decide to reveal their identity to their surroundings, partly because they sometimes fear for their safety. MacEntee thus raises the question: what is the best way to honor the memory of our ancestors? It’s important to consider our particular situation. Sometimes, revealing the LGBTQ+ identity of our ancestors can be perceived as a betrayal, while other times, it’s a way to give them the voice and visibility they were denied during their lifetime (MacEntee, 2007). It is also possible to take note of this information but choose whom to reveal it to and protect it, for instance, with a password.

Nevertheless, bringing visibility to LGBTQ+ stories within our families allows us to have a more accurate and comprehensive portrait of our ancestors. Not to mention, some genealogists today are part of the LGBTQ+ community or practice polyamory (see Our Prairie Nest or Blandón Traiman, 2018a) and may want to document their realities. As mentioned in the introduction, this also allows us to show that LGBTQ+ realities are not new but are human experiences common to all places and times and thus contribute, on our scale, to the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights.

Audrey Pepin

1 To be cisgender means identifying with the gender assigned at birth. Conversely, transgender individuals identify with a gender different from the one assigned at birth and thus undergo a social, legal, and/or medical transition to live with a gender identity that aligns with their own.

2 The term “queer” serves as both an umbrella term used to refer to LGBTQ+ individuals and an identity embraced by those who refuse to define their sexuality and/or gender through labels.

3 This section of the article provides a summary of various recommendations found in the numerous blog articles consulted. Further details are available in the mentioned articles, all listed in the bibliography at the end of this article.

4 It is important to note that men were more targeted in police operations aimed at homosexual individuals; therefore, this tool may be more useful for your research on male ancestors. Although women may have benefited from this targeting at the time, it’s also another way in which their history is currently rendered invisible.

5 The genealogist Stewart Blandón Traiman has extensively reflected on this topic, and if you’re interested, I highly recommend visiting his blog (Blandón Traiman, 2018b).

6 By ethical non-monogamy, I refer to relationship models where partners can have sexual and/or romantic relationships with more than one person. For non-monogamy to be ethical, the individuals involved must be aware of the agreement and have given their enthusiastic, free, and informed consent

7 Polyamory is defined as a practice, an identity, or a relational orientation that involves a consensual, transparent, and honest romantic relationship with multiple partners simultaneously. It is thus a form of ethical non-monogamy

Bibliography :

Beaulieu-Kratchanov, Léa (2023). ” ‘C’est déshumanisant’ : l’impact de la haine anti-trans sur les jeunes”. Pivot Québec. Accessed on November 20th 2023 https://pivot.quebec/2023/09/26/cest-deshumanisant-limpact-de-la-haine-anti-trans-sur-les-jeunes/

Blandón Traiman, Stewart (2018a). LGBT Genealogy – The Six Generations (blog). https://sixgen.org/category/lgbtq-genealogy/

Blandón Traiman, Stewart (2018b). LGBT Genealogy and Softwares – The Six Generations (blog). https://sixgen.org/category/lgbtq-genealogy/lgbtq-genealogy-software/

Collins, Rosemary (2022). ”How to Trace LGBT Ancestors” Who do you Think you Are (online magazine). Accessed on November 17th 2023 https://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/feature/how-to-trace-lgbt-ancestors

Kobel, Becks (2017). ”Genealogy in the Works: Being Gay in Genealogy” The Hipster Historian (blog). Accessed on November 20th 2023 https://thehipsterhistorian.com/2017/02/06/genealogy-in-the-works-being-gay-in-genealogy/

Koeven, Mary (2018). ”Non-traditional Family Trees: Homosexual Relationships”. The Handwritten Past : Professional Genealogists (blog). Accessed on November 20th 2023 https://thehandwrittenpast.com/2018/07/28/recording-homosexual-relationships-in-your-genealogy-database/

Leclerc, Michael J. (2023). ”5 Tips for Finding Your LGBTQIA+ Ancestors”. Ancestry (blog). Accessed on November 16th 2023 https://blogs.ancestry.com/cm/5-tips-for-finding-your-lgbtq-ancestors/

MacEntee, Thomas (s.d). ”Finding Your LGBT Ancestors”. My Heritage (blog). Accessed on Novemebr 16th 2023. https://education.myheritage.com/article/finding-your-lgbt-ancestors/

MacEntee, Thomas (2007). ”The Hidden – LGBT Family Members and Genealogy”. Destination : Austin Family (blog). Accessed on November 20th 2023 https://destinationaustinfamily.blogspot.com/2007/10/hidden-lgbt-family-members-and.html

Magnan-St-Onge, Carolanne (2020). ”Droit de la famille : le polyamour au banc des accusés” Observatoire des réalités familiales du Québec (online publication). Accessed on November 20th 2023. https://www.orfq.inrs.ca/droit-de-la-famille-le-polyamour-au-banc-des-accuses/

Massoud, Rania (2023). ”Identité de genre : après la rue, une offensive dans les écoles en vue”. Radio-Canada. Accessed on November 20th 2023. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/2012019/identite-genre-ecoles-kamel-cheikh

McKee, Mary (2022). ”How to Trace LGBT Ancestors”. Find my Past (blog). Accessed on November 16th 2023. https://www.findmypast.com/blog/help/lgbt-ancestors

Neaves, Jessica (2020). ”How to Search for Your LGBTQ Ancestors”. Heritage Discovered (blog). Accessed on November 17th 2023 https://www.heritagediscovered.com/blog/how-to-search-for-your-lgbtq-ancestors

Waldemar, Heather (s.d). ”How to Create a Family Tree with Flying Logic”. Flying Logic (Website). Accessed on November 20th 2023. https://flyinglogic.com/1498/how-to-create-a-family-tree-with-flying-logic/