This post is also available in: Français

(This is a 3 part article. Click to read: Part 2, Part 3)

When starting this articles project about feminism and genealogy, I first asked myself what I could have to say about it. I had developed a certain expertise in feminist theory through my studies and activism, but I only knew genealogy from afar. Therefore, I started by doing some research in the library of my university, the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM), and on the internet. I tried different keyword combinations with “genealogy”, both in English and in French: “women”, “feminism”, “patriarchy”, “sexism” …

The first thing I noticed was that women, in genealogical research as in many other fields, were often left aside.

Several specialists confirmed that Quebec wasn’t an exception: according to Francine Cousteau Serdongs, who was a lecturer at UQÀM in social work and a genealogy graduate and practitioner, very few genealogists know the name of their uterine pioneer (the woman at the origin of a women lineage, traced from mother to daughter) (Cousteau Serdongs, 2008: 131). She also stressed that the terms that are used in genealogical research seem to forget about women: for example, an ancestry is rarely called patrilineal because it is considered so by default. Another example would be the French word “fratrie”, which means a group of siblings and is directly derived from “frère” which means brother.

Quebec historian Mathieu Drouin pointed out that patrilineal genealogy is the “most known – and generally the easiest way – to rebuild one’s ancestry”[1] (Drouin, 2015) and that matrilineal genealogy is rather “counterintuitive”. Quebec historian, demographer and genealogist René Jetté made the same observation in his Traité de généalogie (Genealogy Treatise) in asserting that patrilineal genealogy is the “most ancient and most popular form” (Jetté, 1991: 110).

Finally, Pierre-Yves Dionne, genealogist and author of De mère en fille. Comment faire ressortir la lignée maternelle de votre arbre généalogique (From Mother to Daughter: How to bring out the maternal line of your family tree) (2004), insists on the fact that in Quebec as in most Western societies, women’s last names almost always come from a man (their husband or their father). He therefore uses genealogy to develop the basis of an eventual transmission of the name of a common female ancestor to subsequent generations of girls. That is exactly what Francine Cousteau Serdongs did: Cousteau is the last name of her uterine pioneer, the first woman in her matrilineage to set foot in New France (Cousteau Serdongs, 2008: 145).

Although the role played by women in history are increasingly emphasized (for example, see Yves Landry’s book on the King’s Daughters, 1992) and some concrete efforts are made to facilitate genealogical research about women (for example, the Drouin Genealogical Institute includes in its Great Collections the Féminine (or Women series), an alphabetical directory of marriages sorted by the bride’s name), I will show in this article that we are not done working on the women’s place in genealogy. Genealogy, like the rest of our society, is based on a patriarchal foundation that we can only deconstruct on the long term. With this first series of articles, I will look into the situation of women in genealogical research in Quebec. I will first explain why women are less present than men in genealogical research. I will then show, in the next articles, what are the consequences of this absence and what possible solutions we can put forward.

As mentioned earlier, our society, genealogical practices included, is a patriarchal society. As underlined by Geneviève Pagé, professor of political science at UQÀM, “patriarchy doesn’t mean that all women are submitted to all men, but that the men’s group, in general, is dominating the women’s group. Therefore, it is not because one woman has had a lot of power […] that we are no longer living in a patriarchal society” (Pagé, 2017: 354). Even though a lot of progress was made by women and feminists in history, in genealogy and in the rest of society, we are still living in a patriarchal system. In genealogy, the marginality of matrilineal lineages that many experts have put forward confirms it. In the rest of our society, it is well shown by the wage inequality, the underrepresentation of women in places of power (such as political institutions) and their overrepresentation in statistics of domestic violence and sexual assault (Pagé, 2017: 353-354).

Patriarchy has forged, through history, a sexist heritage that we didn’t actively construct but that we need to deal with. This heritage partially explains why women’s lineages are invisible in our research. Researchers can indeed have a hard time because of the way last names are passed on. First of all, the fact that women’s last names change every generation, while men pass on their last name to their progeny, makes matrilineal lineages less obvious.

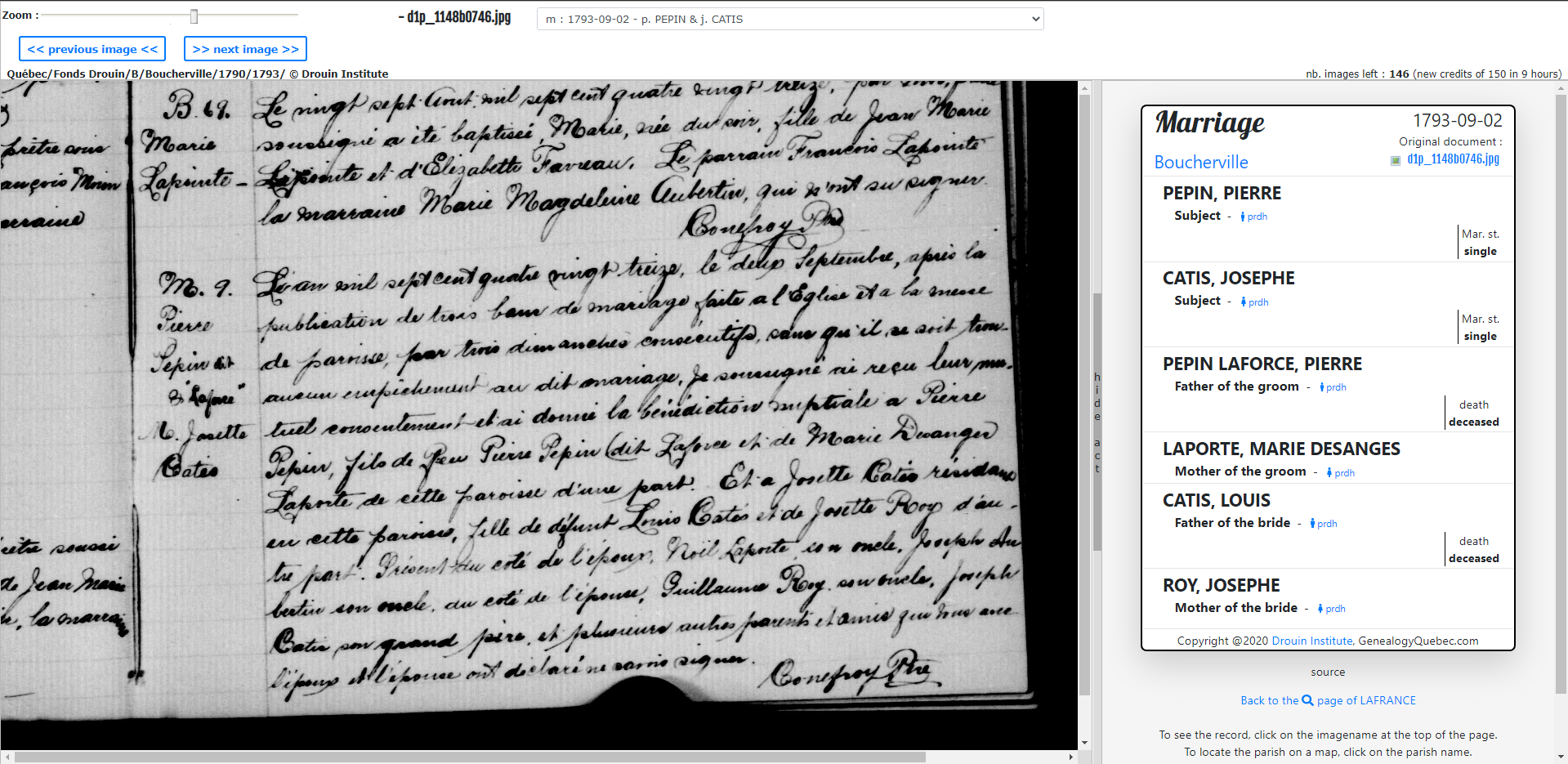

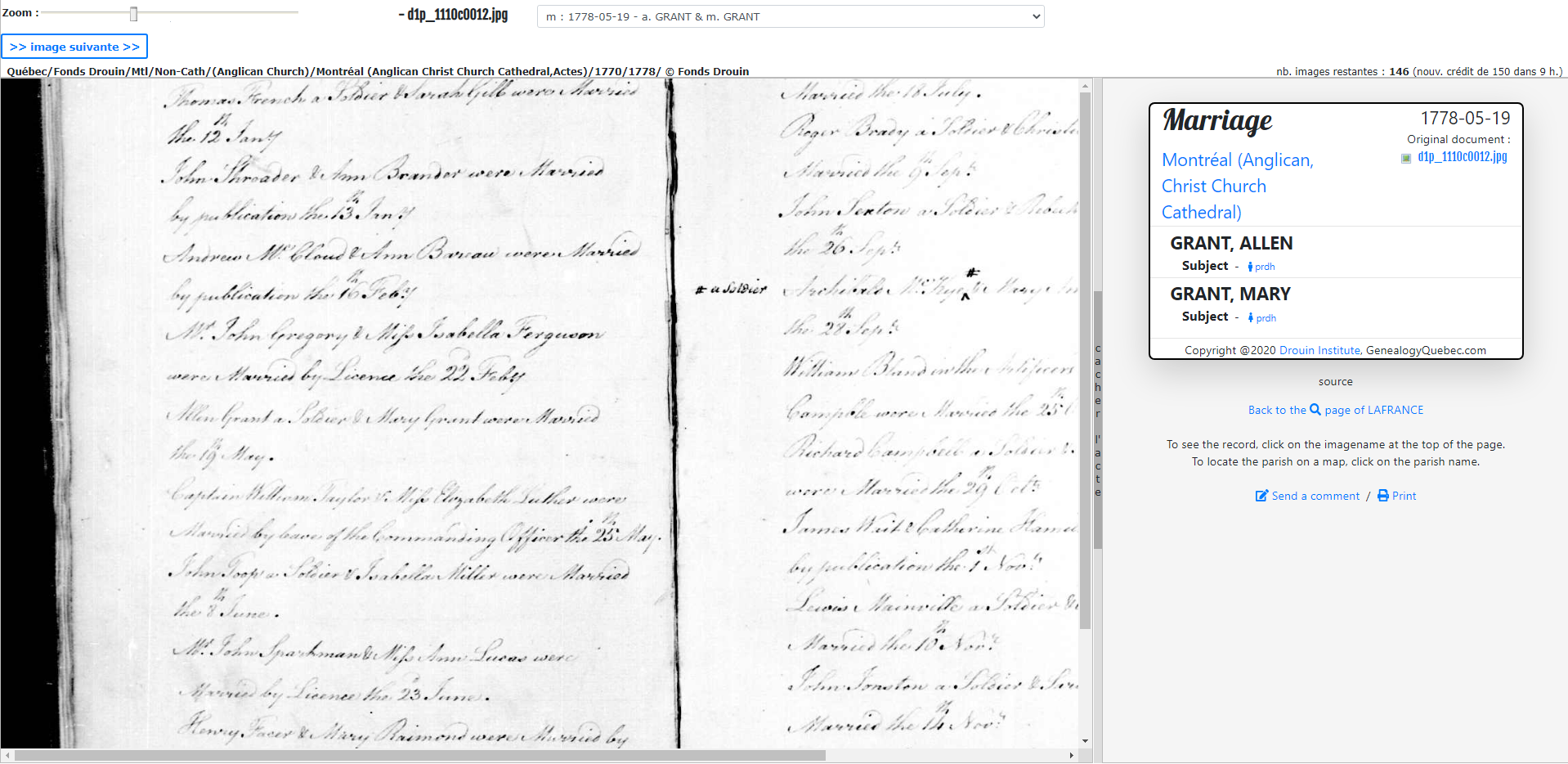

Second, marriage sometimes muddies the waters when it comes to researching women. In Catholic records, women would keep their maiden name in any event that concerned them directly (marriage(s) and death) and even in records that concerned their spouse (remarriage and death) or their children (births, marriages and deaths), but in Protestant registers and historical Canadian censuses until the beginning of the 20th century, women were generally only referred to by the last name of their husband as long as he was alive, and even after (Jetté, 1991 : 436).

Judy Russell, an American genealogist and law graduate, specifies that, in her country, other factors may make it difficult to retrace women in a genealogical research. The fact that they rarely received any inheritance, that they couldn’t take legal action in their name, own land or even open a bank account erased their names from many registers (Clyde, 2017). Those are additional sources: in general, we use marriages, deaths and births records to construct a family tree. Fortunately, Quebec archives are pretty exhaustive in that matter (Jetté, 1991 : 432), but there are always a couple of forgotten individuals and when those are women, they are more difficult to retrace.

Although we didn’t actively construct this patriarchal heritage, I believe it is the responsibility of each and every one of us to work toward a world where we are all equals. After all, these practices that put forward men’s lineages, we reproduce them day after day and we have the power to change them. Thus, Francine Cousteau Serdongs questions the way genealogy is organised as a science as well as how individuals themselves perpetuate these ideas in their own practice of genealogy (2008: 132). In the next two articles, I will detail the consequences of this erasure on the lives of women and I will explore some potential solutions.

Audrey Pepin

[1] Quotes which were originally in French have been translated by the author of this article

Bibliography

Clyde, Linda. (2017a, 26 avril). Ever Wonder Why It’s So Hard to Trace Your Female Ancestry? Family Search [Blog]. https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/ever-wonder-why-its-so-hard-to-trace-your-female-ancestry

Cousteau Serdongs, Francine. (2008). Le Québec, paradis de la généalogie et « re-père » du patriarcat : où sont les féministes? De l’importance d’aborder la généalogie avec les outils de la réflexion féministe. Recherches féministes vol. 21, no. 1, p.131-147. https://doi.org/10.7202/018313ar

Dionne, Pierre-Yves. (2004). De mère en fille : comment faire ressortir la lignée maternelle de votre arbre généalogique. Sainte-Foy : MultiMondes Editions ; Montreal : Remue-Ménage Editions, 79 p.

Drouin, Mathieu. (2015). Patrilinéaire, mitochondriale et agnatique : trois façons de faire votre généalogie! Histoire Canada.

Jetté, René. (1991). Traité de Généalogie. Montreal : Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 716 p.

Landry, Yves. (1992). Orphelines en France, pionnières au Canada. Les Filles du roi au XVIIe siècle suivi d’un répertoire biographique des Filles du roi. Montreal : Bibliothèque Québécoise Editions, 280 p.

Pagé, Geneviève. (2017). La démocratie et les femmes au Québec et au Canada in La politique québécoise et canadienne, Gagnon et Sanschagrin (dir.), 2nd Edition. Quebec : Presses de l’Université du Québec, p.353 à 374.

Reny, Paule and des Rivières, Marie-José. (2005). Compte-rendu de Pierre-Yves Dionne De mère en fille. Comment faire ressortir la lignée maternelle de votre arbre généalogique. Montréal, Les Éditions Multimondes et les éditions du remue-ménage, 2004, 79 p. Recherches féministes, vol. 18, no. 1, p.153-154. https://doi.org/10.7202/012550ar