This post is also available in: Français

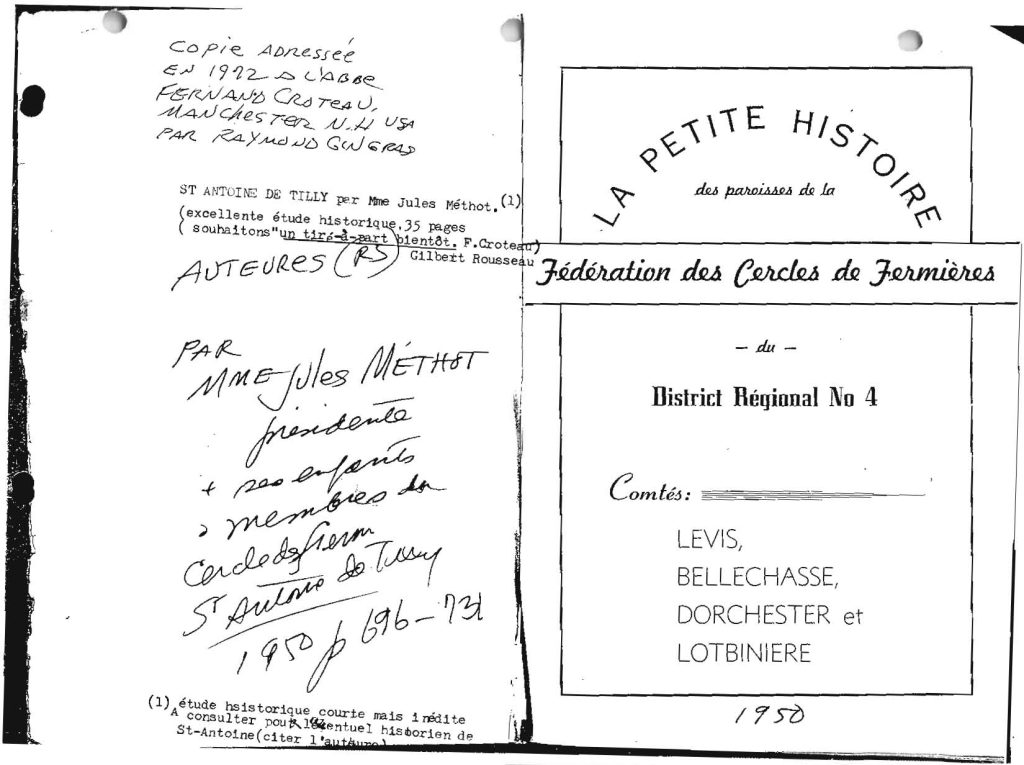

A couple of weeks ago, as I was going through Genealogy Quebec’s databases, I found a folder in the Raymond-Gingras fund named ”Cercle de Fermières” (Women Farmers’ Circle).

Inside, I found a series of photographs of a short text produced by a Women Farmers’ Circle, which tells the story of Saint-Antoine-de-Tilly, a small municipality located in Chaudière-Appalaches. I was curious. Women Farmers’ Circles… I remembered seeing this name somewhere. I knew it was a women’s association who did crafts. Not much more. Intrigued, I did more research.

What are Quebec Women Farmers’ Circles ?

In fact, Women Farmers’ Circles are not only a women’s association, but the first women’s association in Quebec ! They were founded in 1915 (a bit ironically) by a man, Alphonse Désilets, an agronomist who defended “the principle of rural associations to resolve the crisis of the modern world”1 (Cohen, 1990 : 28). The members of the association were, as its name indicates, farmers, and they came together in the Circles mainly to help each other in their various tasks and to better meet the needs of their families. They ran cooperative gardens, helped each other make clothes for the family, all sorts of things which helped improve their quality of life. The groups were then under the direction of the Ministry of Agriculture, in concert with the Church.

From 1940, the Circles progressively gained autonomy, until they no longer depended on the Church or the State. As Quebec urbanized, there were fewer and fewer farmers among the members, but the group chose to keep its name. Despite the evolution of society, we can observe a certain continuity in the activities of the Circles : members are still doing crafts, knitting, weaving and cooking. They consider themselves guardians of the craft and culinary heritage (Beaudoin et Joncas, 2021 : 46) and transmit their knowledge to younger members or the larger community. The Circles are also an important space of sociability for the women who participate and they help break isolation, among retired women for example. Women Farmers’ Circles finally have a political function, helping their members stay informed as citizens, trying to influence government policies, but also by maintaining links with various organizations (such as the Associated Country Women of the World, the Coalition for Gun Control, Canadian Breast Cancer Network, etc.) (Lagarde, 2015 : 5).

Women Farmers’ Circles and feminism

Even though they are a women’s association, now run by and for women, Quebec Women Farmers’ Circles do not impose themselves, at first glance, as feminist groups. Indeed, the Circles have spoken out against women’s right to vote and against the right to abortion. Their positions evolved over time, but the Circles are still promoting the roles traditionally attributed to women, such as caring for the family and domestic work. This posture further distances them from feminist demands, which often link emancipation and the possibility for women to break out of stereotypes and gender roles if they wish to do so.

Nevertheless, in my opinion, it would be disproportionate to completely exclude them from the history of feminism in Quebec. Indeed, the Circles worked hard to improve the living conditions of women and have been a driving force for promoting the activities typically practiced by women, in particular by promoting the culinary and artisanal achievements of their members. They are also a space in which the ethics of care2 can be lived and practiced. Indeed, the Women Farmers’ Circles were created at first to to promote mutual aid between members, but beyond this mission, the Circles also take care of their wider communities, for example through the organization of community meals, volunteering and partnerships with charities or their influence on public policy3. Above all, although the Circles promote the traditional roles that women occupy in the private sphere, they were, and in some respects may still be today, a public space that women can fully inhabit, where they can express themselves, do organizational work, and even do politics4, in short, where they can learn typical male work but do it in their own way.

Women Farmers’ Circles therefore occupy a very particular position in our history and are victims of a double erasing : we don’t talk about them much when we do the history of Quebec, because we don’t talk much about women in general; but we also speak little about them when we construct a history of women from a feminist perspective, since their positions deviated (and still deviate, in certain respects) from those taken by the feminist movement. It’s nevertheless impossible to deny the role the Circles played, both globally in the history of Quebec society and more specifically in the history of women in Quebec. They were one of the first drivers of women’s empowerment and affirmation, encouraging them to leave the private and family sphere (Cohen, 1990: 263). The Circles also participated fully in the development of the national project. Indeed, through their requests made to the State and their rejection of the influence of the clergy on their organization, they participated in the establishment of two central pillars to the development of Quebec: the development of a modern and protective State and the deconfessionalization of society (Cohen, 1990: 263).

Like any organization, it is of course best not to idealize the Women Farmers’ Circles and to underline their limits, particularly in terms of feminist positioning. However, it also seems essential to make their contribution to the history of women and Quebec society visible.

To learn more about Quebec Women Farmers’ Circles, I invite you to read Yolande Cohen’s book Femmes de Parole : l’histoire des Cercles de Fermières du Québec (1990) (although as far as I know, it’s only available in French) or to watch the documentary All That We Make, directed by Annie Saint-Pierre (2013).

1 This quote was translated from French by the author of this article.

2 Ethics of care are based in the maintenance of human relationships as well as in the interdependence of individuals. Care aims to ‘’maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web’’ (Fisher and Tronto, 1990 : 40). For more details, you can read my article about genealogy and care here. It’s also important to note that these ethics can be linked to the christian values of the organization.

3 They are notably at the origin of programs for the distribution of milk cartons in schools (Radio-Canada, 2015).

4 I’m thinking in particular of the women who are involved in the organization of the Circles and who are democratically elected as presidents, whether at regional or national level.

Bibliography

Beaudoin, Christiane and Joncas, Gisèle. « Le Cercle de Fermières de Gaspé : 50 ans par et pour les femmes ». Magazine Gaspésie, vol.57, no.3 (199), p.46-48.

Cohen, Yolande (1990). Femmes de parole : l’histoire des Cercles de Fermières du Québec 1915-1990. Montréal : Le Jour Éditeur, 315 pages.

Lagarde, Louise (2015). « Les Cercles de Fermières du Québec : 100 ans de savoir à partager ». Histoire Québec, vol.20, no.3, p.5-9.

Radio-Canada (2015). « Les Cercles de Fermières », segment of the show L’épicerie, 13:37 – 18:10. Consulted February 13th 2023 : https://curio.ca/fr/catalog/533431a2-2c93-4945-b476-f87009fc0158

Saint-Pierre, Annie (2013). All That We Make, documentary.

Fisher, Berenice and Tronto, Joan. (1990). ”Towards a Feminist Theory of Care”. In Circles of care, Abel, E. and Nelson, M. (ed.). New York : State University of New York Press, p.36-54.