When one is interested in one’s ancestry and reconstructs a lineage through genealogical research, one also sees the history of the transmission of family name(s). This may seem insignificant to us, because for a long time this history was obvious: the question of the transmission of the family name did not really arise, since the family name of the father was systematically given to the children. There was no need to think about it.

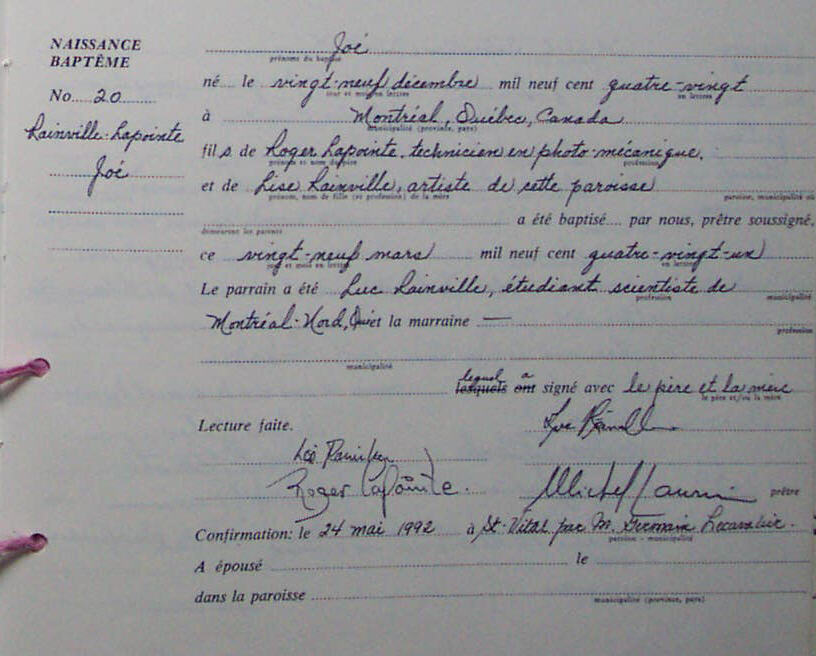

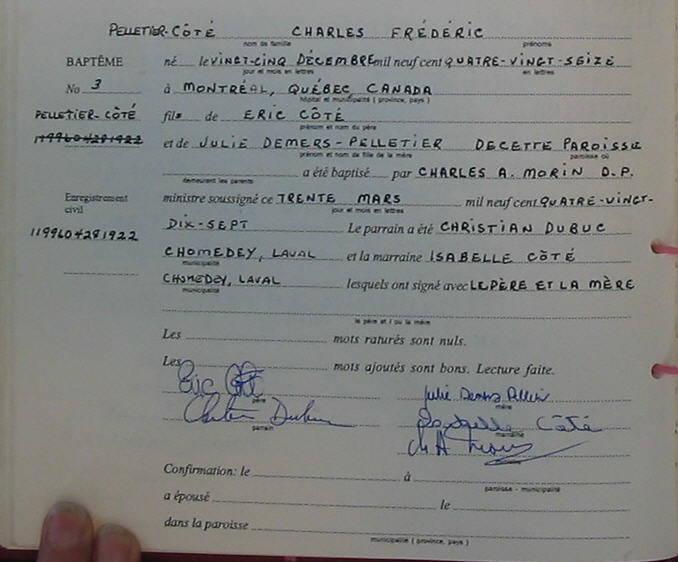

But in 1981, the reform of the civil code, and more precisely of family law, allowed Quebec women to give their family name to their children. Suddenly, the choice of which family name to pass on became an issue: one could give a family name, that of the father or the mother, or choose to pass on both. In this context, it becomes particularly interesting to observe the ways in which surnames are passed from one generation to the next. Forty years later, what has been the impact of the 1981 reform? What relationship do Quebec women have with their family name, and why do they choose (or not) to pass it on?

Marie-Hélène Frenette-Assad decided to explore these questions by producing the podcast Le nom de ma mère (Frenette-Assad, 2020) available for free on Radio-Canada’s Ohdio platform.1

Marie-Hélène Frenette-Assad is a podcast producer, musician, consultant and trainer in digital audio. She also has, as you may have noticed, two last names, her father’s and her mother’s. However, she finds that her friends, the women of her generation, don’t often pass on their names to their children, nor is it a topic of discussion they often bring up. And this is not just an anecdotal observation – statistics also indicate a decrease in the transmission of the double family name in Quebec (Frenette-Assad, 2020: episode 5).

In Le nom de ma mère (The name of my mother), Marie-Hélène discusses with her own mother why she gave her a double surname and explores, throughout the podcast, her relationship to her surname. But she also brings in women who participated in the 1981 reform, experts who study the issue, and a variety of women from her generation who have a different relationship to their surnames and who decide to give it to their children, or not, for different reasons. Often, these are women who themselves have a double surname, and who should potentially split it to give only one to their children.

Because yes, a generation after the 1981 reform, situations arise where both members of a couple have two surnames.. It would obviously become quickly unmanageable if both parents transmitted their two surnames and we ended up with quadruple surnames, then octuple, and so on! If a couple both have a double surname and want to pass it on to their child, they will have to make a choice. In the podcast, we learn that the instigators of the reform had originally thought that mothers could pass on their mother’s surname, and fathers, their father’s surname. The idea is similar to the proposal of Pierre-Yves Dionne (2004), which I have discussed in previous articles2 – he suggested that future generations of women should be given the name of a common ancestor (the uterine pioneer), so that women’s surnames would no longer always come from a man.

However, in practice, this is not always the case. There are many factors other than gender that come into play when making a decision about passing on a name. Some women, for example, choose to pass on the name associated with the extended family to which they feel closest, regardless of the gender of the parent. Some also consider the presence or absence, in their family, of other people with the same name who have passed it on or could pass it on to their children. For example, they mention wanting to pass on one of their names that would otherwise go extinct.

Other women do not see themselves choosing between their two names, either because they see their name as indivisible, or because they do not want to hurt the parent whose name would be “rejected”. Since this is not an option for them, they prefer not to give their name at all!

Others are thinking about the effect that the name will have on their children’s lives: sometimes the double name is experienced as an obstacle, whether in certain professional environments where self-branding is important, or in everyday life because we become annoyed that people forget our full name or because one of the names is difficult to pronounce. But the double name is also sometimes perceived as a strength, something that allows one to stand out and whose uniqueness makes it beautiful, even poetic (as is the case for columnist Rose-Aimée Automne T. Morin).

However, despite all this reasoning that moves away from gender concerns, the issue remains clearly political and feminist. Some women claim that they “have given themselves the chance to exist in their children’s names”3 (Frenette-Assad, 2020: episodes 2 and 3). They see it as a way of recognizing the role of women in filiation and the passing on of the heritage. Others mention the importance of honoring past feminist struggles by exercising their right to pass on their names to their children. For my part, as I listened to the podcast and repeatedly heard women question whether their names are “too long,” I couldn’t help but think of the many ways in which women are constantly asked to make themselves smaller. In particular, many feminist researchers and theorists have documented how various social norms (and the attitudes of some men) push women to wear restrictive clothing (from corsets to high heels), not to speak too loudly or too long, not to take up too much space with their bodies, etc. (Young, 2005; Yaguello, 2002). In particular, manspreading has made a lot of noise in recent years (Morin, 2017). Could we add having a “not too long” last name to the list?

It is very interesting to note that the issue also has an intersectional component: it is indeed posed differently, for example, for adopted people, who often have a different relationship with their surname because it does not reflect their genetic heritage; or for people with an immigrant background, whose surname is sometimes a bearer of prejudice, but also represents an important link with the country of origin. On a more personal note, I grew up with a single mother who gave me her family name – and only her family name. I wear it proudly: it represents for me the strength of women who find themselves, by spite or by choice, to be the only parental figure.

The reality of homosexual couples, and in particular lesbian couples, is also particular and occupies an entire episode of the podcast (Frenette-Assad, 2020: episode 4). Indeed, in their case, the passing on of the family name cannot be “taken for granted”: when both parents are women, one cannot avoid a real reflection by invoking tradition since there is no male parent who could pass on his name “by default”. Of course, most of the issues we have already discussed apply in the case of lesbian couples as well, but since very often the child carries the genetic baggage of only one of their two mothers, a concern is added: that of a symbolic transmission of a legacy that is not biological, through the transmission of the name.

If you are interested in the issue of double surnames, I highly recommend listening to the podcast Le nom de ma mère, available free of charge on the Ohdio platform of Radio-Canada.

Audrey Pepin

1 A special thanks to documentarian Fanny Germain who, during a discussion on matrilineality, introduced me to this very interesting podcast!

2 See the series of articles ” The omission of women in family trees “.

3 Quote freely translated by the author of this article

Bibliography :

Frenette-Assad, Marie-Hélène (2020). Le nom de ma mère. Podcast available online: https://ici.radio-canada.ca/ohdio/balados/7434/nom-famille-mere-femme-enfant

Dionne, Pierre-Yves (2004). De mère en fille : comment faire ressortir la lignée maternelle de votre arbre généalogique. Sainte-Foy: Éditions MultiMondes; Montréal: Éditions du Remue-Ménage, 79 p.

Morin, Violaine (2017). “Comment le ‘’manspreading’’ est devenu un objet de lutte féministe” Le Monde [Online]:

Yaguello, Marina (2002 [1978]). Les mots et les femmes. Paris : Éditions Payot. 257 p.

Young, Iris Marion (2005). On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays. Oxford University Press: 192 p.