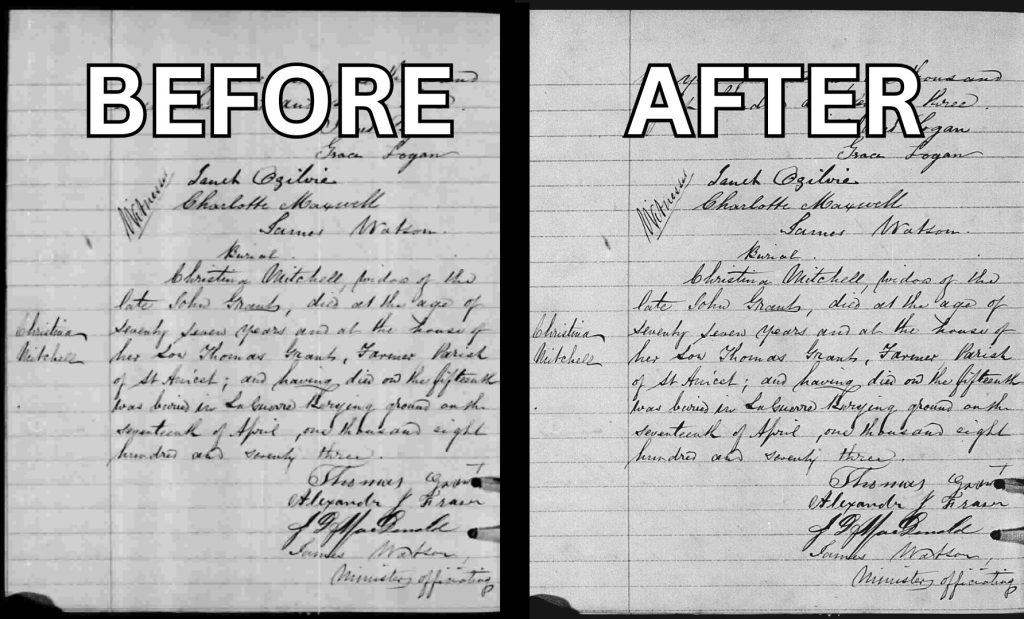

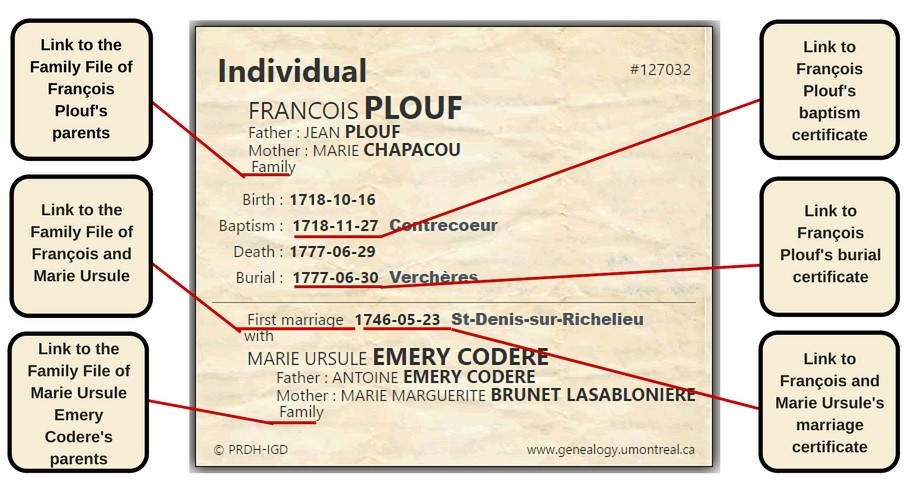

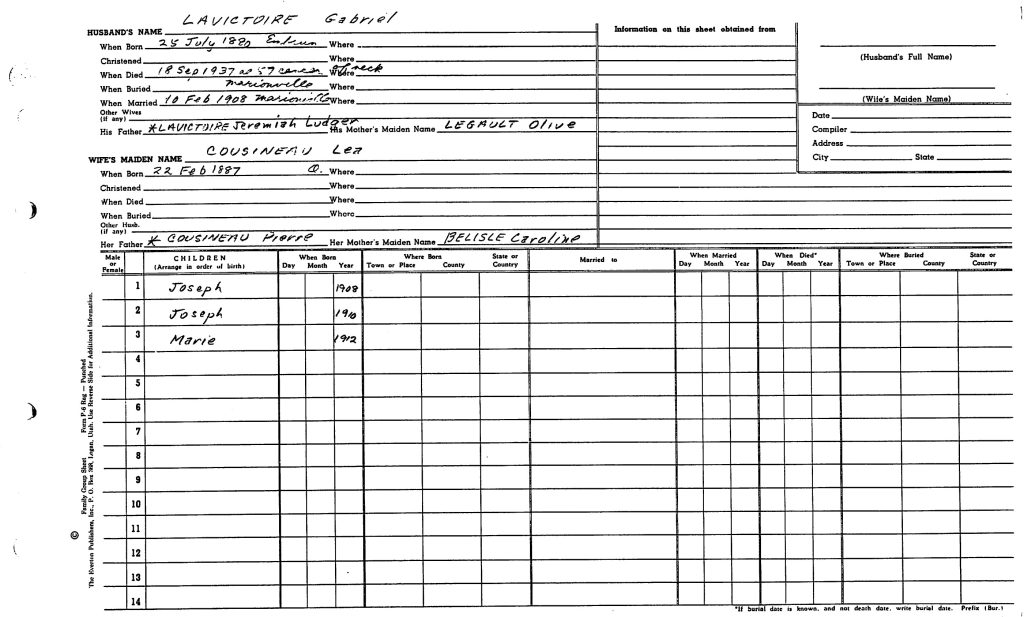

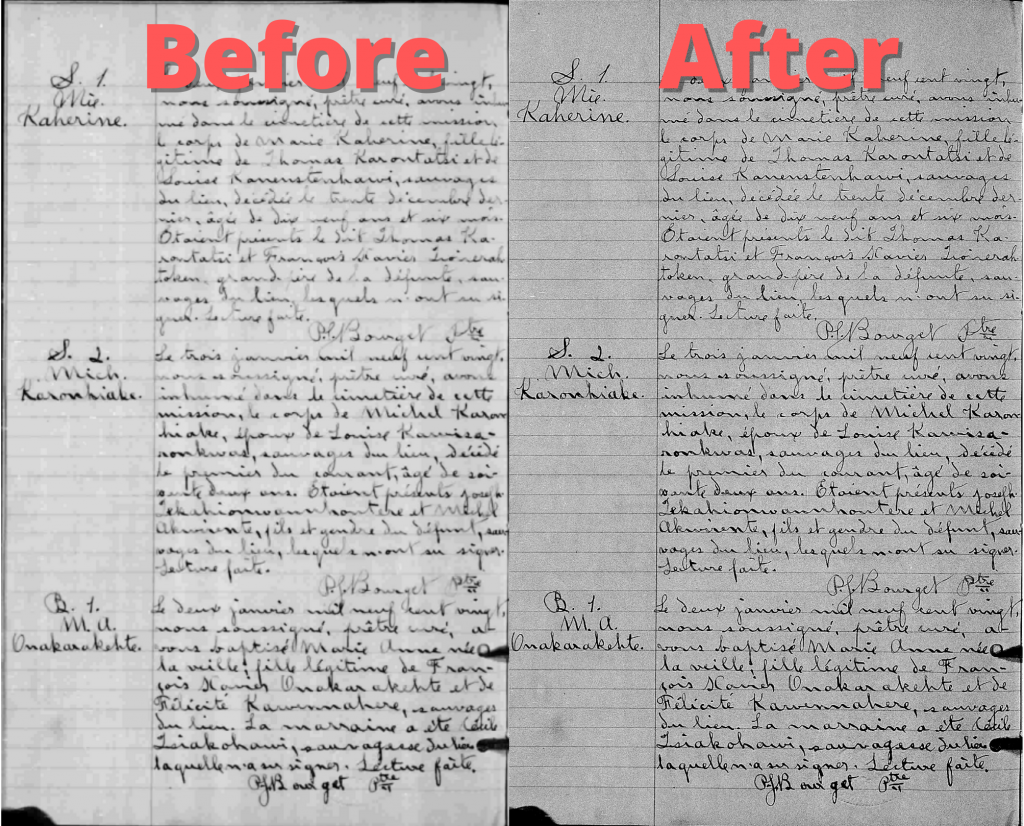

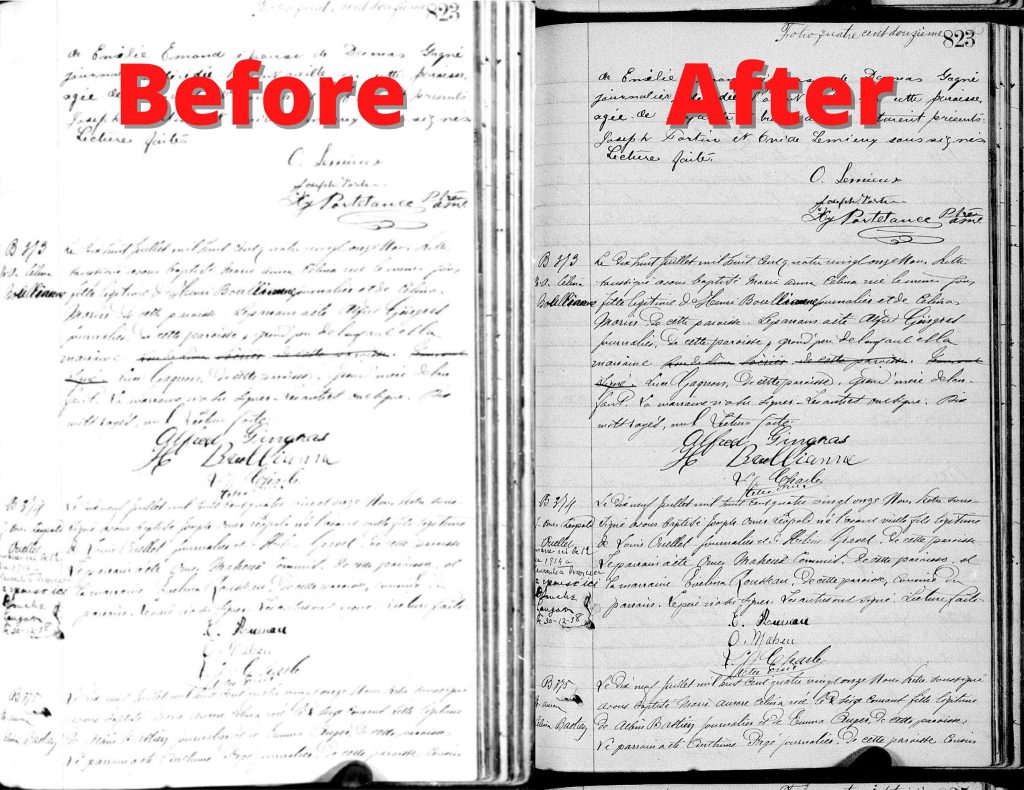

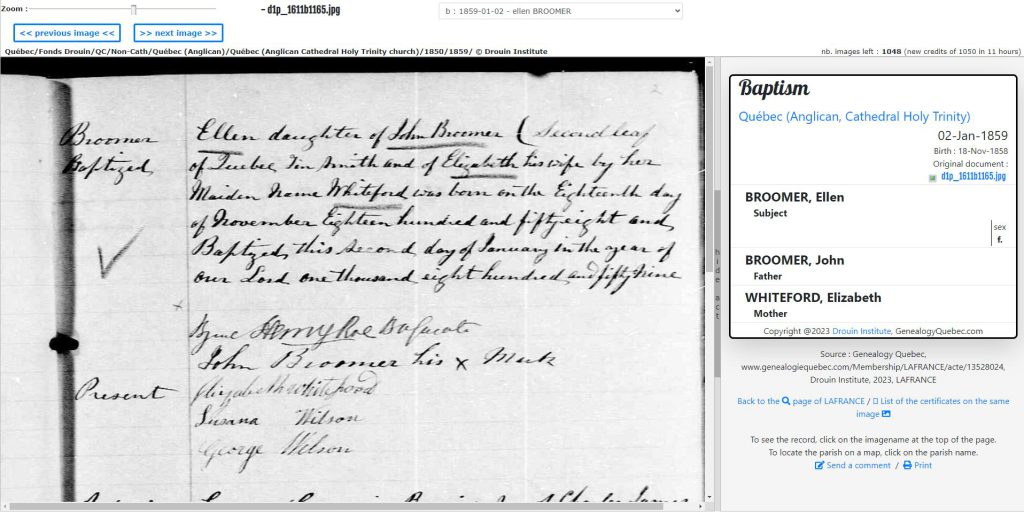

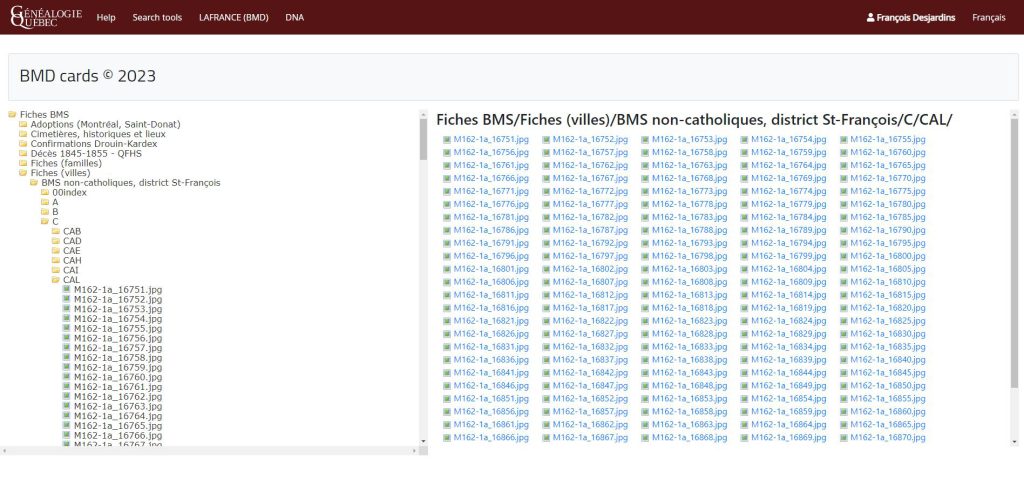

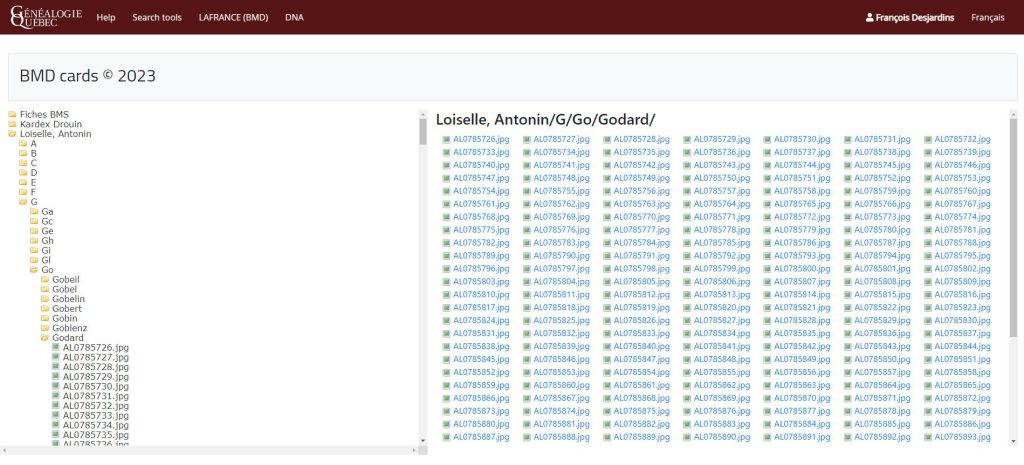

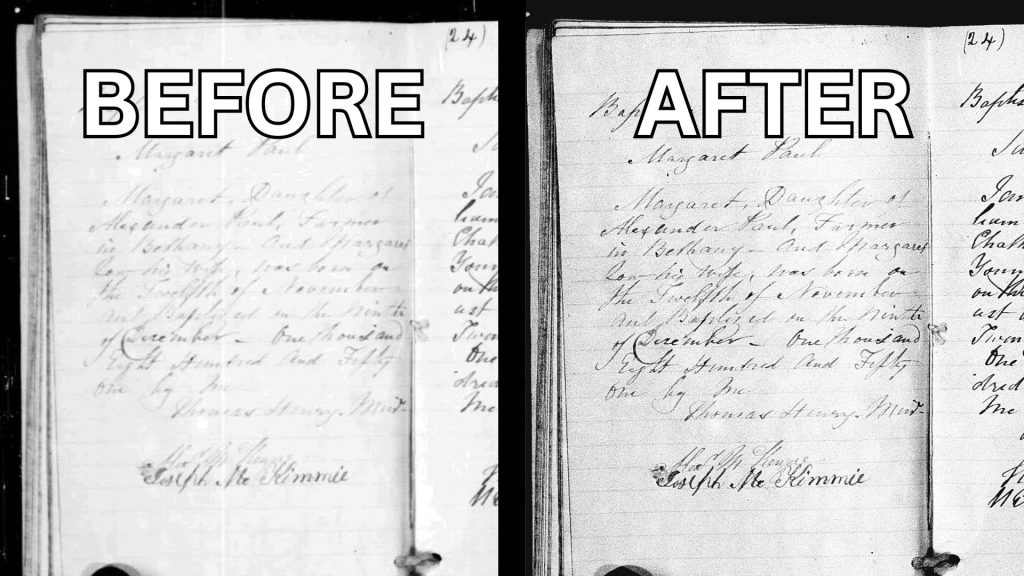

51,000 images from the registers of 227 Quebec parishes have been rescanned on Genealogy Quebec to improve their clarity.

To this day, over 1.35 million Drouin collection images have been rescanned and are available exclusively on Genealogy Quebec.

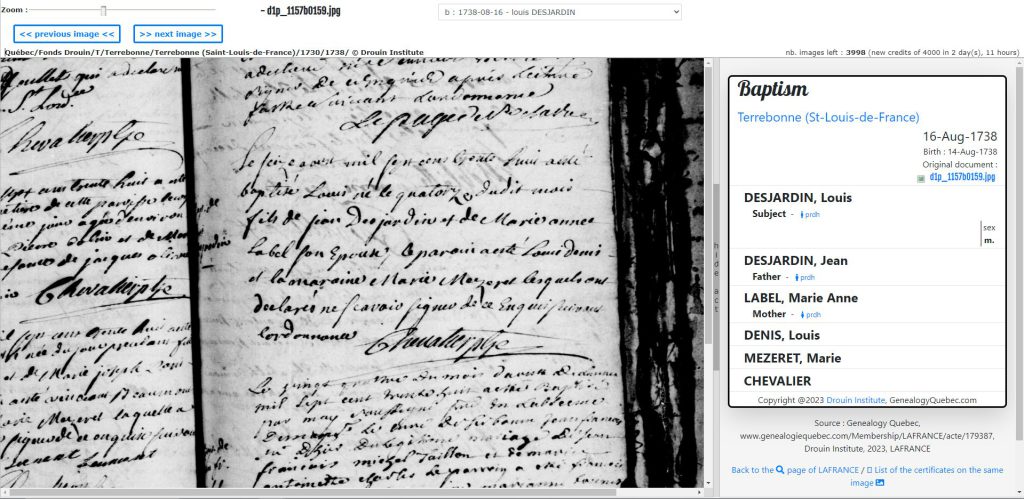

Source: Drouin Collection Records, GenealogyQuebec.com

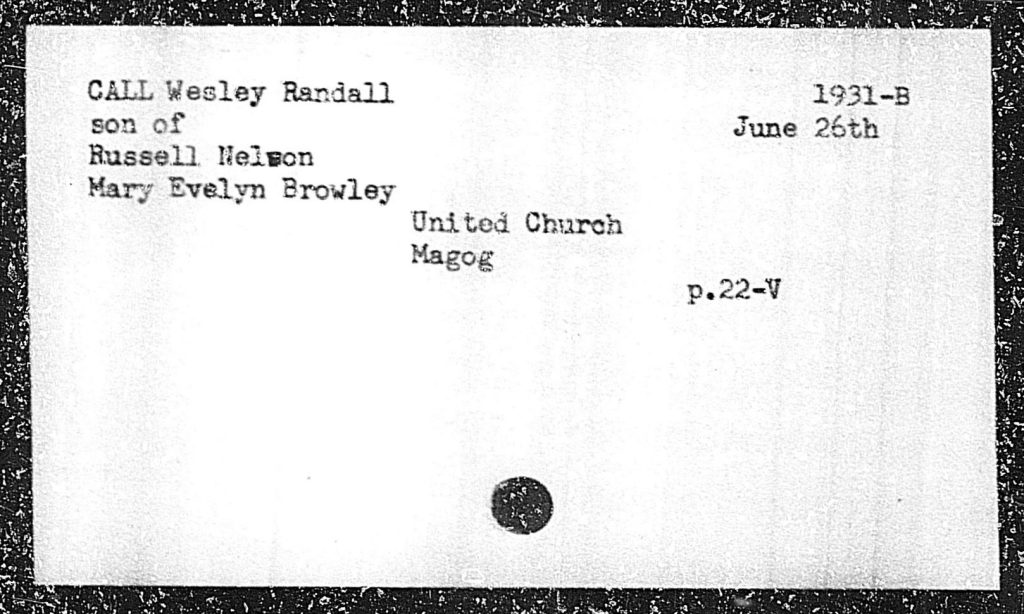

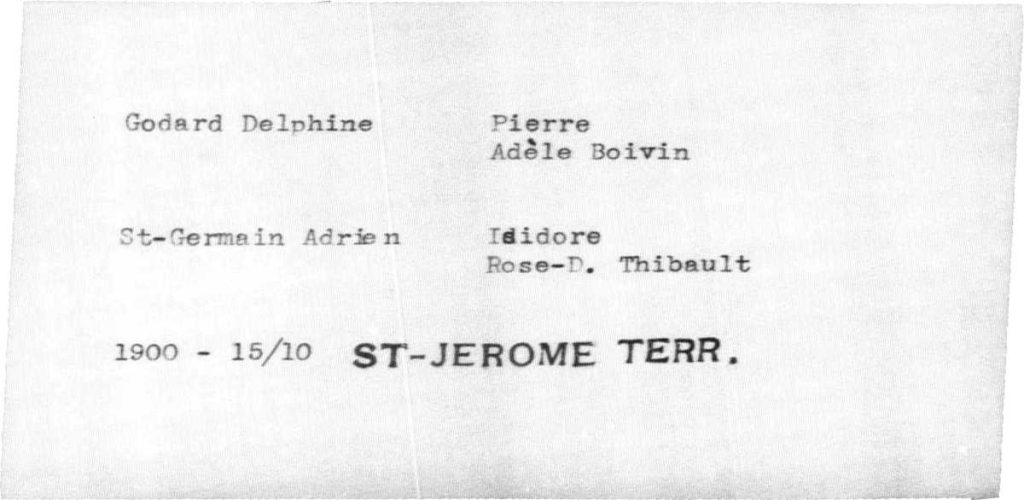

The resolution of these new images is two to three times higher than that of the previous copy, which ensures great legibility.

Browse all of Quebec’s parish registers as well as millions of historical documents by subscribing to Genealogy Quebec today.

Get 25% off the yearly subscription if you subscribe by June 24th!

A monthly subscription is also available at this address.

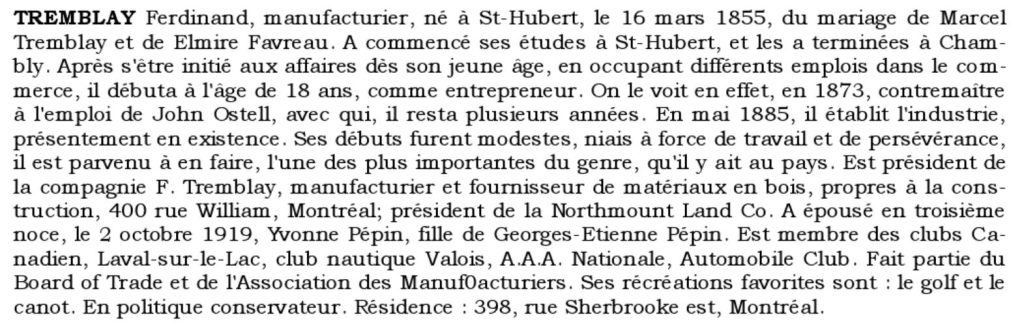

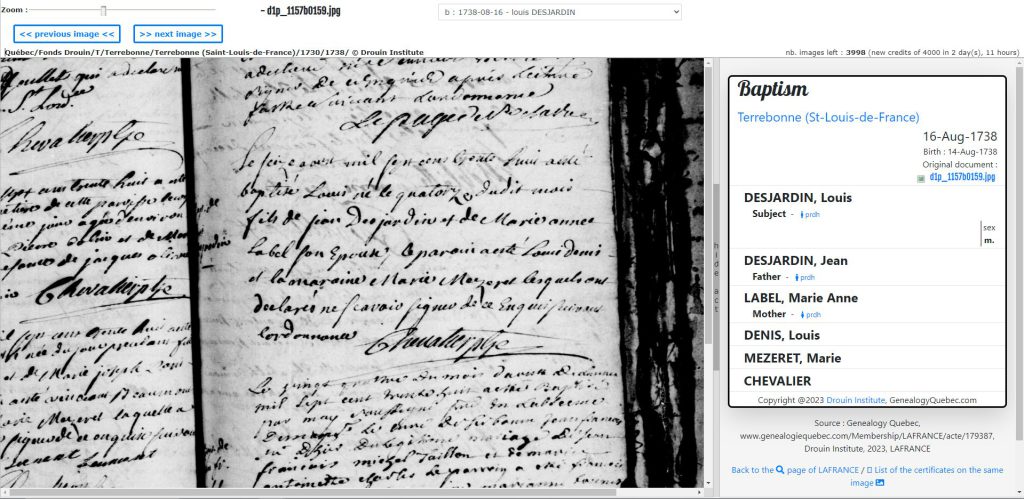

The Drouin Collection Records

The Drouin Collection Records are a collection of parish registers (baptisms, marriages and burials) covering all of Quebec and French Acadia as well as parts of Ontario, New Brunswick and the Northeastern United States, from the parish’s foundation up to the 1940s and sometimes 1960s.

You can browse the Drouin collection with a subscription to Genealogy Quebec at this address.

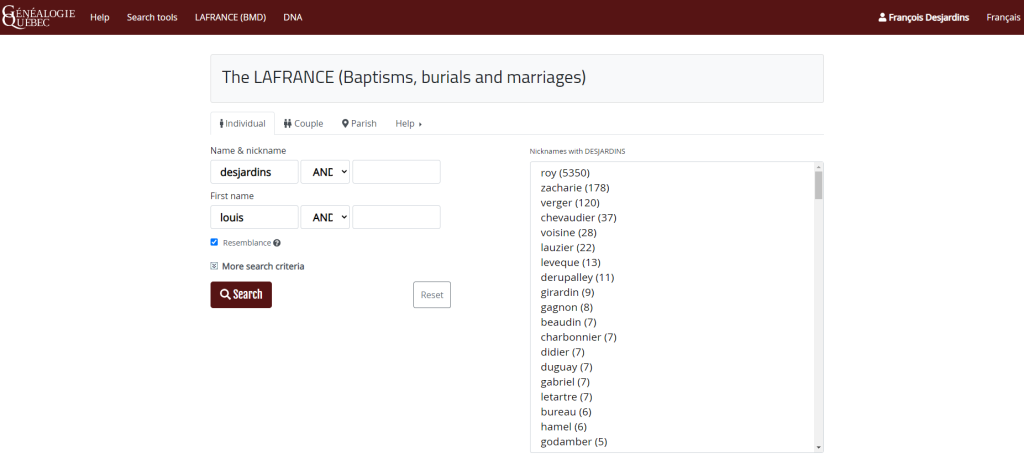

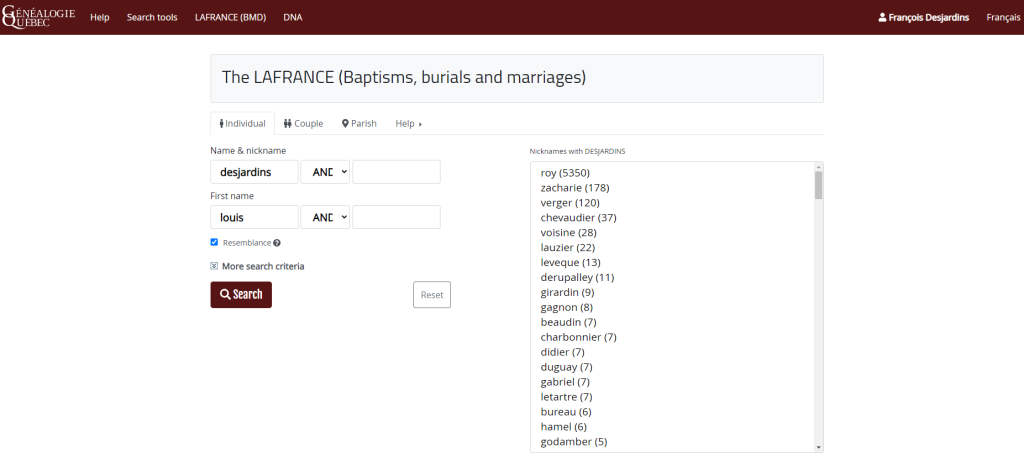

The LAFRANCE, also available to Genealogy Quebec subscribers, is a search engine allowing you to explore these parish registers by names.

You can browse the LAFRANCE at this address.

List of rescanned parishes

Here are the parishes that have been rescanned in this update.

| Parish | Year(s) |

|---|---|

| Abbott Corner (Baptist Church) | 1897-1911 |

| Arundel (Anglican Church) | 1902-1942 |

| Arundel (Church of England) | 1869-1915 |

| Arundel (Episcopal Church) | 1892 |

| Arundel (Holiness Movement) | 1898-1922 |

| Arundel (Methodist Church) | 1876-1923 |

| Arundel (Presbyterian Church) | 1875-1923 |

| Arundel (Protestants) | 1897 |

| Arundel (Standard Church) | 1936-1940 |

| Arundel (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Avoca (Baptist Church) | 1912-1942 |

| Avoca (Presbyterian Church) | 1895-1920 |

| Avoca (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Bedford (Anglican Church) | 1851-1864 |

| Belle-Rivière (Church of Scotland) | 1834 |

| Belle-Rivière (Église évangélique) | 1862-1887 |

| Belle-Rivière (Presbyterian Church) | 1888-1915 |

| Bolton (Anglican, Saint Andrew) | 1862 |

| Bolton (Baptist Church) | 1864-1941 |

| Bolton West (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1928-1942 |

| Brome (Baptist Church) | 1879-1884 |

| Brome (Congregational Church) | 1842-1854 |

| Brownsburg (Anglican Church) | 1923 |

| Brownsburg (Baptist Church) | 1936-1938 |

| Brownsburg (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Buckland (Notre-Dame-Auxiliatrice) | 1857-1862 |

| Calumet (Methodist Church) | 1888-1919 |

| Calumet (Pentecostal Church) | 1935-1940 |

| Calumet (Protestants) | 1937-1941 |

| Calumet (United Church) | 1938-1940 |

| Carillon (Methodist Church) | 1890 |

| Chapeau (St-Alphonse) | 1883-1929 |

| Clarenceville (Anglican Church) | 1852-1854 |

| Clarenceville (Baptist Church) | 1887-1942 |

| Cowansville (Anglican Church) | 1854-1864 |

| Cowansville (Congregational Church) | 1845 |

| Cowansville (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1925-1930 |

| Cushing (Presbyterian Church) | 1892-1921 |

| Cushing (United Church) | 1939-1942 |

| Dalesville (Baptist Church) | 1877-1942 |

| Drummondville (Anglican Church) | 1823-1942 |

| Dunham (Church of England) | 1848 |

| Dunham (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1930 |

| Dunkin (Baptist Church) | 1924 |

| Durham (Baptist Church) | 1859-1873 |

| Durham (Congregational Church) | 1842-1919 |

| Durham (Methodist Church) | 1854-1925 |

| Farnham (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1931-1935 |

| Farnham-East (Baptist Church) | 1864-1893 |

| Fort Beauharnois | 1732-1760 |

| Fort Chambly | 1759-1760 |

| Fort Châteauguay | 1751-1762 |

| Fort Presqu’Ile | 1757-1762 |

| Frelighsburg (Anglican Church) | 1852-1942 |

| Frost Village (Anglican Church) | 1857-1864 |

| Gore (Church of England) | 1854-1904 |

| Gore (Episcopal Church) | 1839-1844 |

| Gore (Protestants) | 1879-1895 |

| Granby (Congregational Church) | 1842-1854 |

| Grande-Entrée (Sacré-Cœur) | 1900-1948 |

| Grenville (Anglican Church) | 1914-1942 |

| Grenville (Baptist Church) | 1872-1942 |

| Grenville (Church of England) | 1837-1913 |

| Grenville (Church of Scotland) | 1867 |

| Grenville (Congregational Church) | 1878 |

| Grenville (Methodist Church) | 1860-1923 |

| Grenville (Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs) | 1879-1940 |

| Grenville (Presbyterian Church) | 1844-1914 |

| Grenville (Protestants) | 1937-1938 |

| Grenville (Scotch Presbyterian Church) | 1848-1866 |

| Grenville (United Church) | 1939-1941 |

| Grindstone Island (Protestants) | 1929-1949 |

| Grosse-Île (Protestants) | 1929-1949 |

| Harrington (Methodist Church) | 1889 |

| Harrington (Presbyterian Church) | 1862-1913 |

| Harrington (United Church) | 1935-1942 |

| Havre-Aubert (Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation) | 1793-1929 |

| Havre-Saint-Pierre (St-Pierre) | 1860-1905 |

| Huberdeau (Standard Church) | 1940 |

| Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Protestants) | 1858-1928 |

| Inverness (Anglican Church) | 1859-1925 |

| Inverness (Baptist Church) | 1871-1872 |

| Inverness (Holiness Movement) | 1902-1913 |

| Inverness (Methodist Church) | 1859-1925 |

| Inverness (Presbyterian Church) | 1858-1942 |

| Inverness (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1914-1940 |

| Inverness (Standard Church) | 1927-1928 |

| Inverness (United Church) | 1926-1942 |

| Ireland (Methodist Church) | 1860-1873 |

| Ireland and Maplegrove (Anglican Church) | 1858-1942 |

| Kilkenny (Church of England) | 1874-1905 |

| Kilmar (United Church) | 1935-1942 |

| Kinnear’s Mills (United Church) | 1927-1942 |

| Knowlton (Anglican Church) | 1856 |

| Knowlton (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1901-1911 |

| Lac-Beauport (St-Dunstan) | 1834 |

| Lachute (Anglican Church) | 1912-1942 |

| Lachute (Baptist Church) | 1884-1942 |

| Lachute (Church of England) | 1869-1911 |

| Lachute (Episcopal Church) | 1879-1893 |

| Lachute (Free Church) | 1859-1862 |

| Lachute (Methodist Church) | 1852-1923 |

| Lachute (Presbyterian Church) | 1842-1942 |

| Lachute (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Lake View (Presbyterian Church) | 1897-1905 |

| Lakefield (Anglican Church) | 1901-1942 |

| Lakefield (Church of England) | 1890-1910 |

| Lakefield (Episcopal Church) | 1892-1896 |

| Lakefield (Methodist Church) | 1881-1909 |

| Lakefield (Protestants) | 1936-1938 |

| Lakefield (Trinity Church) | 1939 |

| L’Ancienne-Lorette (Notre-Dame-de-l’Annonciation) | 1777-1800 |

| Leeds (Anglican Church) | 1855-1942 |

| Leeds (Methodist Church) | 1858-1909 |

| Leeds (Presbyterian Church) | 1858-1939 |

| L’Étang-du-Nord (St-Pierre) | 1863-1868 |

| Lost River (Presbyterian Church) | 1896-1923 |

| Mabel (Baptist Church) | 1923 |

| Mansonville (Baptist Church) | 1909-1942 |

| Mascouche (Methodist Church) | 1880 |

| Mille-Isles (Anglican Church) | 1908-1942 |

| Mille-Isles (Christ Church) | 1941 |

| Mille-Isles (Church of England) | 1862-1912 |

| Mille-Isles (Presbyterian Church) | 1864-1940 |

| Mille-Isles (Protestants) | 1920-1922 |

| Morin (Church of England) | 1862-1888 |

| Morin (Protestants) | 1920 |

| Morin Flats (Holiness Movement) | 1906-1910 |

| Morin Heights (Anglican Church) | 1909-1942 |

| Morin Heights (Christ Church) | 1941 |

| Morin Heights (Methodist Church) | 1915-1916 |

| Morin Heights (Protestants) | 1942 |

| Morin Heights (Trinity Church) | 1936-1940 |

| Morin Heights (United Church) | 1938-1942 |

| New Glasgow (Anglican Church) | 1910-1942 |

| New Glasgow (Church of England) | 1870-1915 |

| New Glasgow (Methodist Church) | 1875-1915 |

| New Glasgow (Presbyterian Church) | 1875-1940 |

| New Glasgow (United Church) | 1941-1942 |

| North Gore (Church of England) | 1852-1869 |

| North Gore (Methodist Church) | 1867-1875 |

| Notaire André Bouchard dit Lavallée | 1834-1874 |

| Notaire Augustin Mackay | 1827-1872 |

| Notaire Blotters | 1852-1858 |

| Notaire Jean-Moïse Lefebvre | 1863-1881 |

| Notaire Joseph Ledoux | 1868-1872 |

| Notaire Joseph Lesiège dit Lafontaine | 1856-1886 |

| Notaire Joseph Turgeon | 1783-1808 |

| Notaire Joseph-Paul Filiatrault | 1832-1852 |

| Notaire Louis-Adélard-A. Brien | 1886-1919 |

| Notaire Louis-Hector J. Bellerose | 1875-1900 |

| Notaire Paul Filiatrault | 1838-1852 |

| Notaire Pierre-Rémi Gagnier | 1784-1817 |

| Notaire Stephan Mackay | 1821-1859 |

| Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix (Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix) | 1909 |

| Noyan & Foucault (Anglican Church) | 1858-1864 |

| Oka (Methodist Church) | 1870-1909 |

| Oka (Pentecostal Church) | 1935-1942 |

| Oka (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Ottawa (Ste-Brigide) | 1890-1907 |

| Philipsburg (Anglican Church) | 1809-1942 |

| Philipsburg (Congregational Church) | 1845-1853 |

| Ponsonby (Methodist Church) | 1896-1900 |

| Potton (Anglican Church) | 1856-1864 |

| Potton (Baptist Church) | 1911-1915 |

| Potton (Methodist Church) | 1846 |

| Registre des Notaires de Detroit | 1778-1796 |

| Repentigny (La Purification-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie) | 1679-1810 |

| Rivington (Baptist Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Roussillon (Baptist Church) | 1921-1923 |

| Roxton Pond (Baptist Church) | 1876-1942 |

| Salaberry (Presbyterian Church) | 1875-1910 |

| Shawbridge (Methodist Church) | 1866-1922 |

| Shawbridge (Protestants) | 1942 |

| Shawbridge (United Church) | 1936-1941 |

| Shefford (Anglican Church) | 1852-1854 |

| Shefford (Baptist Church) | 1939-1942 |

| Shrewsbury (Anglican Church) | 1941 |

| South Ely (Baptist Church) | 1878-1932 |

| St-André-Est (Anglican Church) | 1926-1942 |

| St-André-Est (Christ Church) | 1937-1938 |

| St-André-Est (Methodist Church) | 1855 |

| St-André-Est (Presbyterian Church) | 1897-1942 |

| St-André-Est (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| St-Armand-Est (Baptist Church) | 1864-1915 |

| St-Armand-Est (Church of England) | 1856 |

| Ste-Agathe-des-Monts (Trinity Church) | 1936-1942 |

| Ste-Foy (Notre-Dame-de-Foy) | 1827-1829 |

| Ste-Sophie (État civil) | 1938-1940 |

| Ste-Sophie (Presbyterian Church) | 1866 |

| Ste-Thérèse (Church of Scotland) | 1834 |

| Ste-Thérèse (Presbyterian Church) | 1845-1887 |

| Ste-Thérèse (United Church) | 1888 |

| Ste-Thérèse (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| St-Eustache (Church of Scotland) | 1834-1837 |

| St-Eustache (Presbyterian Church) | 1846-1856 |

| St-Eustache (United Church) | 1936-1942 |

| St-Faustin (Methodist Church) | 1891-1916 |

| St-Faustin (St-Faustin) | 1934 |

| St-Hippolyte-de-Kilkenny (St-Hippolyte) | 1866-1869 |

| St-Jovite (Methodist Church) | 1897-1916 |

| St-Mungo (United Church) | 1848 |

| Stonefield (Baptist Church) | 1896-1921 |

| St-Philippe-d’Argenteuil (Baptist Church) | 1842-1922 |

| St-Philippe-d’Argenteuil (Church of England) | 1837-1860 |

| St-Philippe-d’Argenteuil (Church of Scotland) | 1833-1867 |

| St-Philippe-d’Argenteuil (Methodist Church) | 1861-1907 |

| St-Philippe-D’Argenteuil (Presbyterian Church) | 1844-1899 |

| St-Sauveur-des-Monts (Methodist Church) | 1892 |

| Stukely (Anglican Church) | 1851-1863 |

| St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques) | 1713-1786 |

| Sutton (Baptist Church) | 1864-1942 |

| Sutton (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1931-1937 |

| Sutton, Glen Sutton and West Sutton (Anglican Church) | 1891-1942 |

| Terrebonne (Church of England) | 1872-1918 |

| Thetford Mines (Anglican Church) | 1907-1942 |

| Thetford Mines (Methodist Church) | 1910-1927 |

| Thetford Mines (Secrétaire-trésorier) | 1924-1926 |

| Thetford Mines (United Church) | 1926-1943 |

| Ulverton (United Church) | 1926-1942 |

| Valcourt (Baptist Church) | 1918-1936 |

| Victoriaville (Greffe) | 1929-1942 |

| Ville-Marie (Notre-Dame-du-Rosaire) | 1873-1933 |

| Waterloo (Anglican Church) | 1855-1863 |

| Wentworth (Anglican Church) | 1941 |

| Wentworth (Church of England) | 1869-1881 |

| West Shefford (Anglican Church) | 1855-1863 |

Genealogically yours,

The Drouin team