21,083 new baptism, marriage and burial records are now available on the LAFRANCE, one of 15 tools available to Genealogy Quebec subscribers.

These new records come from 19 Acadian parishes and span from 1796 to 1862.

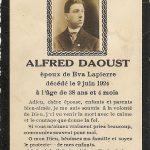

Source: Record 7992792, LAFRANCE, GenealogyQuebec.com

In addition to these new records, the LAFRANCE contains:

- ALL of Quebec’s Catholic marriages from 1621 to 1918

- ALL of Quebec’s Catholic baptisms from 1621 to 1861

- ALL of Quebec’s Catholic burials from 1621 to 1861

- ALL of Quebec’s Protestant marriages from 1760 to 1849

- 1,450,000 Quebec Catholic marriages from 1919 to today

- 80,000 Quebec civil marriages from 1969 to today

- 140,000 Ontario marriages from 1850 to today

- 38,000 marriages from the United States

- 3,000 Quebec Protestant marriages from 1850 to 1941

- 17,000 miscellaneous Quebec marriages from 2018 and 2019

- 68,000 miscellaneous baptisms and burials from 1862 to 2019

More information about the LAFRANCE can be found on the Drouin Institute’s blog.

Trace your ancestors and explore your family history with over 50 million historical images and documents by subscribing to Genealogy Quebec today!

Finally, here is a detailed overview of the added Acadian records by year and location:

| Parish / Location | Type | Start | End | Records |

| Acadie (St-Bernard de Neguac) | b | 1796 | 1799 | 82 |

| Acadie (St-Bernard de Neguac) | m | 1796 | 1798 | 11 |

| Acadie (St-Bernard de Neguac) | d | 1796 | 1799 | 8 |

| Barachois, Nouveau-Brunswick (St-Henri) | b | 1812 | 1862 | 2193 |

| Barachois, Nouveau-Brunswick (St-Henri) | m | 1820 | 1862 | 512 |

| Barachois, Nouveau-Brunswick (St-Henri) | d | 1812 | 1861 | 368 |

| Cap-Pelé (Ste-Thérèse) | b | 1859 | 1862 | 170 |

| Cap-Pelé (Ste-Thérèse) | m | 1860 | 1862 | 20 |

| Cap-Pelé (Ste-Thérèse) | d | 1860 | 1862 | 21 |

| Carleton (St-Joseph) | b | 1819 | 1819 | 42 |

| Carleton (St-Joseph) | m | 1819 | 1820 | 3 |

| Carleton (St-Joseph) | d | 1819 | 1819 | 11 |

| Central Kingsclear (Ste-Anne) | b | 1824 | 1859 | 314 |

| Central Kingsclear (Ste-Anne) | m | 1824 | 1856 | 23 |

| Central Kingsclear (Ste-Anne) | d | 1824 | 1855 | 51 |

| Charlo (St-François-Xavier) | b | 1853 | 1862 | 213 |

| Charlo (St-François-Xavier) | m | 1855 | 1861 | 15 |

| Dalhousie (La-Décollation-de-St-Jean-Baptiste) | b | 1843 | 1843 | 12 |

| Escuminac (Stella-Maris et Baie-Ste-Anne) | b | 1801 | 1861 | 648 |

| Escuminac (Stella-Maris et Baie-Ste-Anne) | m | 1801 | 1861 | 61 |

| Escuminac (Stella-Maris et Baie-Ste-Anne) | d | 1801 | 1855 | 67 |

| Frédéricton (St-Dunstan) | b | 1827 | 1866 | 5083 |

| Frédéricton (St-Dunstan) | m | 1827 | 1861 | 880 |

| Frédéricton (St-Dunstan) | d | 1827 | 1861 | 165 |

| Frédéricton (Ste-Anne) | b | 1806 | 1859 | 602 |

| Frédéricton (Ste-Anne) | m | 1809 | 1859 | 77 |

| Frédéricton (Ste-Anne) | d | 1809 | 1855 | 125 |

| Grande-Digue (Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation-de-Wellington) | b | 1800 | 1862 | 2185 |

| Grande-Digue (Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation-de-Wellington) | m | 1800 | 1862 | 469 |

| Grande-Digue (Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation-de-Wellington) | d | 1802 | 1862 | 512 |

| Johnville (St-Jean-Baptiste) | b | 1861 | 1861 | 2 |

| Lamèque (St-Urbain) | b | 1840 | 1862 | 353 |

| Lamèque (St-Urbain) | m | 1849 | 1860 | 26 |

| Lamèque (St-Urbain) | d | 1848 | 1853 | 14 |

| Milltown (St-Étienne) | b | 1838 | 1862 | 1594 |

| Milltown (St-Étienne) | m | 1838 | 1862 | 255 |

| Milltown (St-Étienne) | d | 1853 | 1861 | 49 |

| Scoudouc (St-Jacques) | b | 1850 | 1862 | 136 |

| Scoudouc (St-Jacques) | m | 1852 | 1861 | 10 |

| Scoudouc (St-Jacques) | d | 1855 | 1861 | 24 |

| Shippagan (St-Jérôme) | b | 1824 | 1862 | 1087 |

| Shippagan (St-Jérôme) | m | 1824 | 1862 | 116 |

| Shippagan (St-Jérôme) | d | 1824 | 1858 | 75 |

| St-François-Xavier (Madawaska) | b | 1859 | 1862 | 193 |

| St-François-Xavier (Madawaska) | m | 1859 | 1861 | 29 |

| St-François-Xavier (Madawaska) | d | 1859 | 1862 | 38 |

| St-Léonard (Madawaska) | b | 1854 | 1861 | 324 |

| St-Léonard (Madawaska) | m | 1854 | 1861 | 14 |

| St-Léonard (Madawaska) | d | 1860 | 1860 | 5 |

| St-Louis-des-Français (St-Louis) | b | 1800 | 1862 | 1411 |

| St-Louis-des-Français (St-Louis) | m | 1802 | 1862 | 252 |

| St-Louis-des-Français (St-Louis) | d | 1802 | 1862 | 213 |

Genealogically yours,

The Drouin team