The Drouin Genealogical Institute, in collaboration with its partner Micromatt, offers a scanning service adapted to your needs and requirements which takes into account your budgetary constraints.

Since 1972, Micromatt has provided a wide range of products and services related to microfilm and electronic document management. Their reputation is built on a personalized approach that takes into account your needs and requirements, the possibilities offered by current technology and your budget realities. Micromatt cares about the success of your archival projects and takes the time to better target appropriate solutions.

In addition to common administrative documents scanning, Micromatt also has the equipment and expertise to digitize your plans and technical drawings, your books and bound documents, even old and fragile, as well as your microfilms on 16 and 35 mm reels, microfiche or aperture cards. Micromatt can even scan very large artworks at very high resolution.

For its part, the Drouin Genealogical Institute specializes in sharing and preserving the historical and genealogical heritage of Quebec. Today, this preservation involves the digitization of the hundreds of millions of documents which reside, often forgotten, in the many libraries, societies and other institutions of the province.

From there was born the Micromatt-IGD collaboration, which aims to offer you a high-quality digitization service accompanied by unique offers made possible by the commercialization of historical and genealogical archives performed by the Drouin Institute.

PLANS AND DRAWINGS

Your large documents, in black or in color, can be converted into digital files to keep, transport and view, even on your mobile platforms. Micromatt can scan your plans, technical drawings, maps and other large documents up to 48 inches wide, even using advanced image processing to improve readability.

DIGITIZATION OF ADMINISTRATIVE DOCUMENTS

Micromatt can take over the scanning of your day-to-day business documents such as contracts, invoices, human resources documents, event and research records, etc.

In addition to the obvious space saving they provide, digitized documents can be viewed and shared without travelling, and they can easily be stored and secured in multiple locations to control access.

While microfilm serves a long-term archival need, digitization can be used on records that you need to access every day.

MICROFORMS SCANNING

While the secure preservation of microfilm documents has now been replaced by digital scanning, there is still a very large quantity of legacy microfilm and microfiche, from which we can also extract indexed digital files to make them accessible and easier to read and share.

BOOK SCANNING

You can now ensure the longevity of your old and precious books, even fragile, entrusting us scanning your bound documents of all sizes. Using highly specialized scanners, ensuring the capture of pages without physical constraints or damaging lighting, our operators will be able to extract high quality images allowing even full text search. This allows you to give broad access to these rare documents more easily to more people.

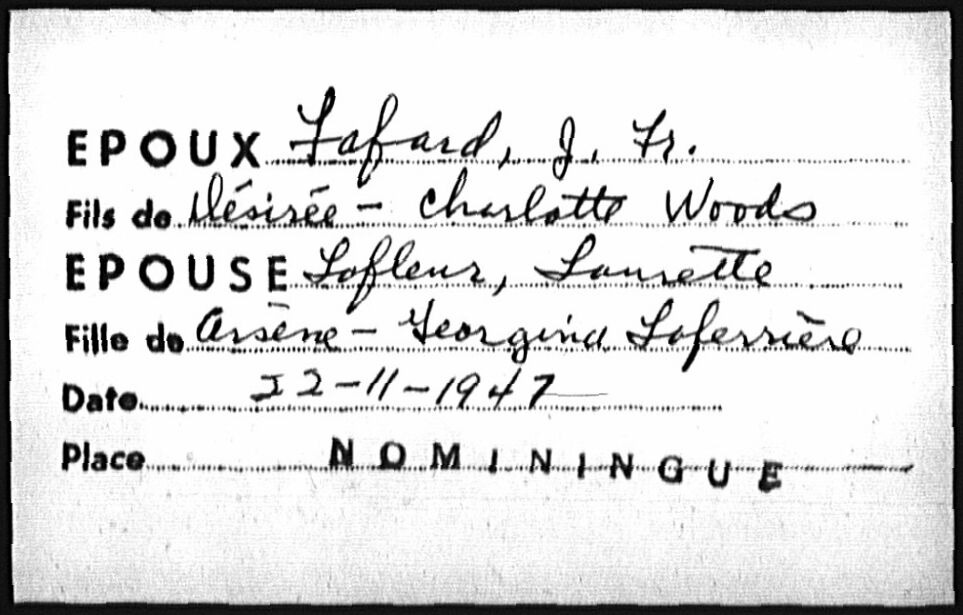

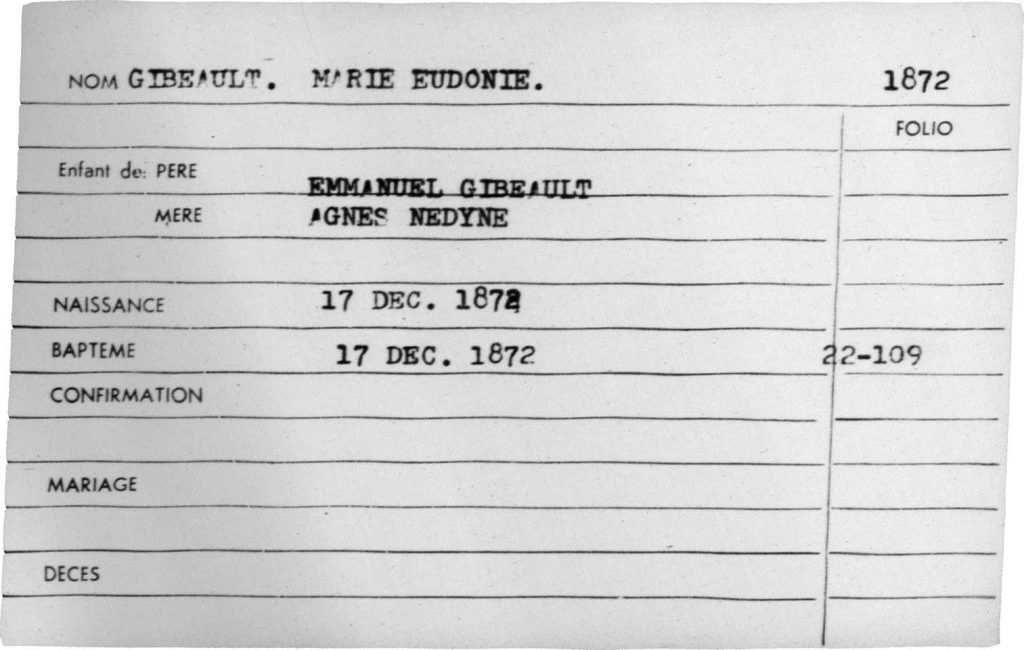

DIGITIZATION OF GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ARCHIVES

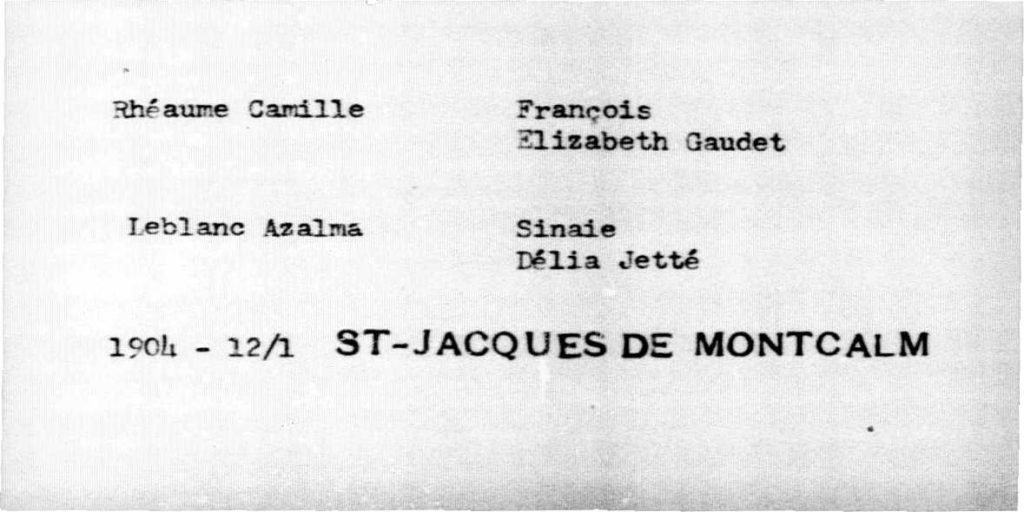

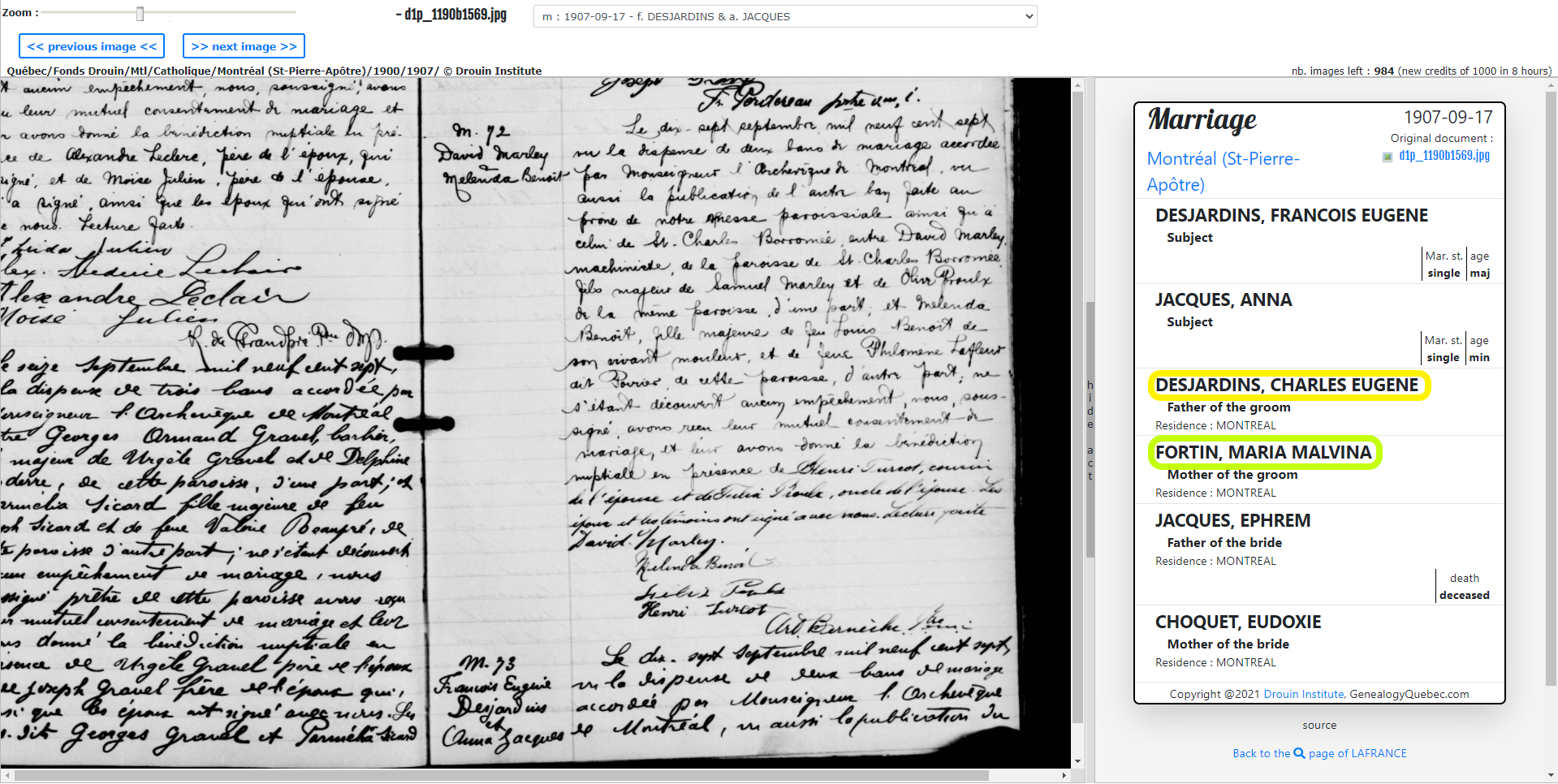

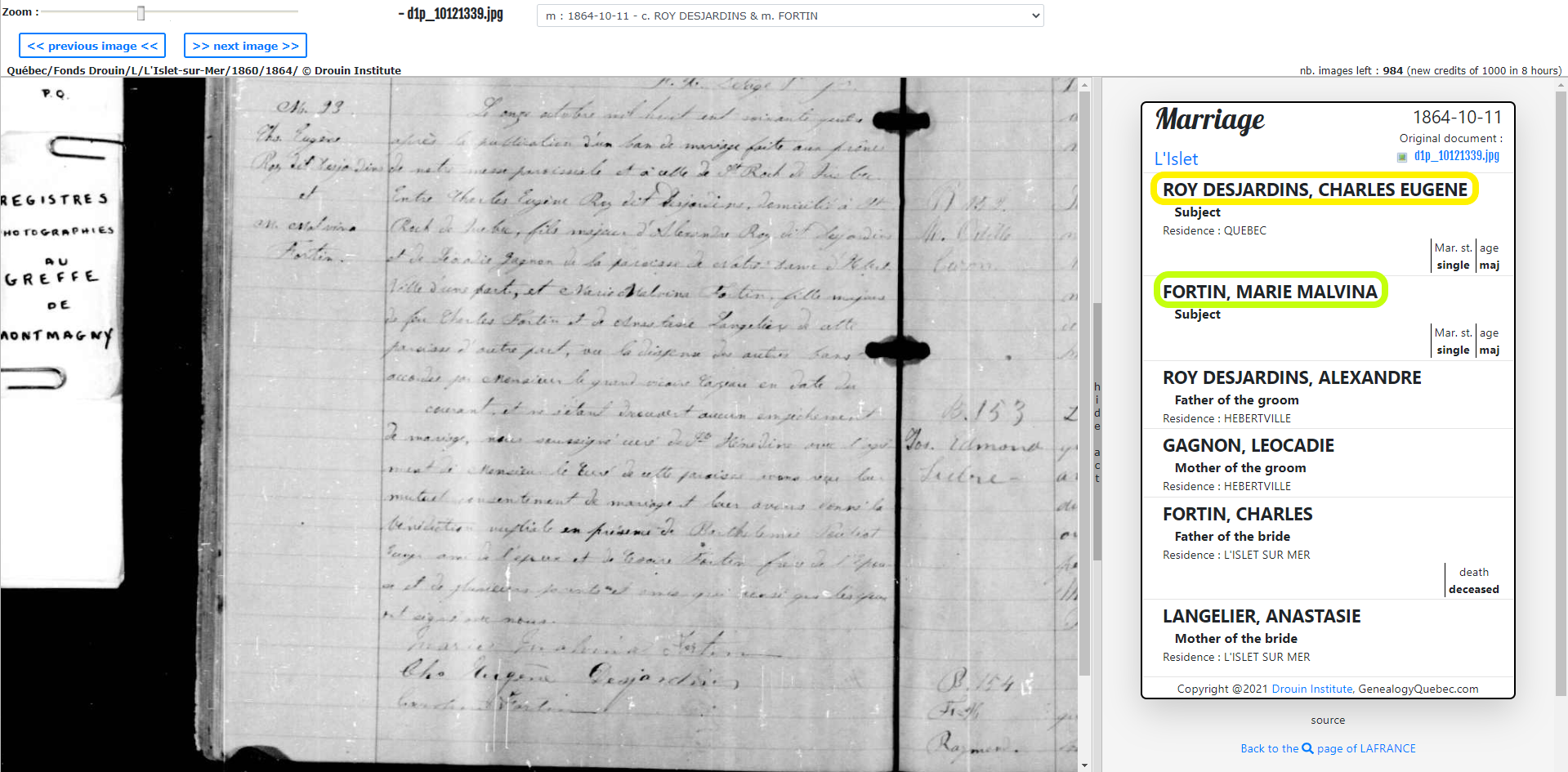

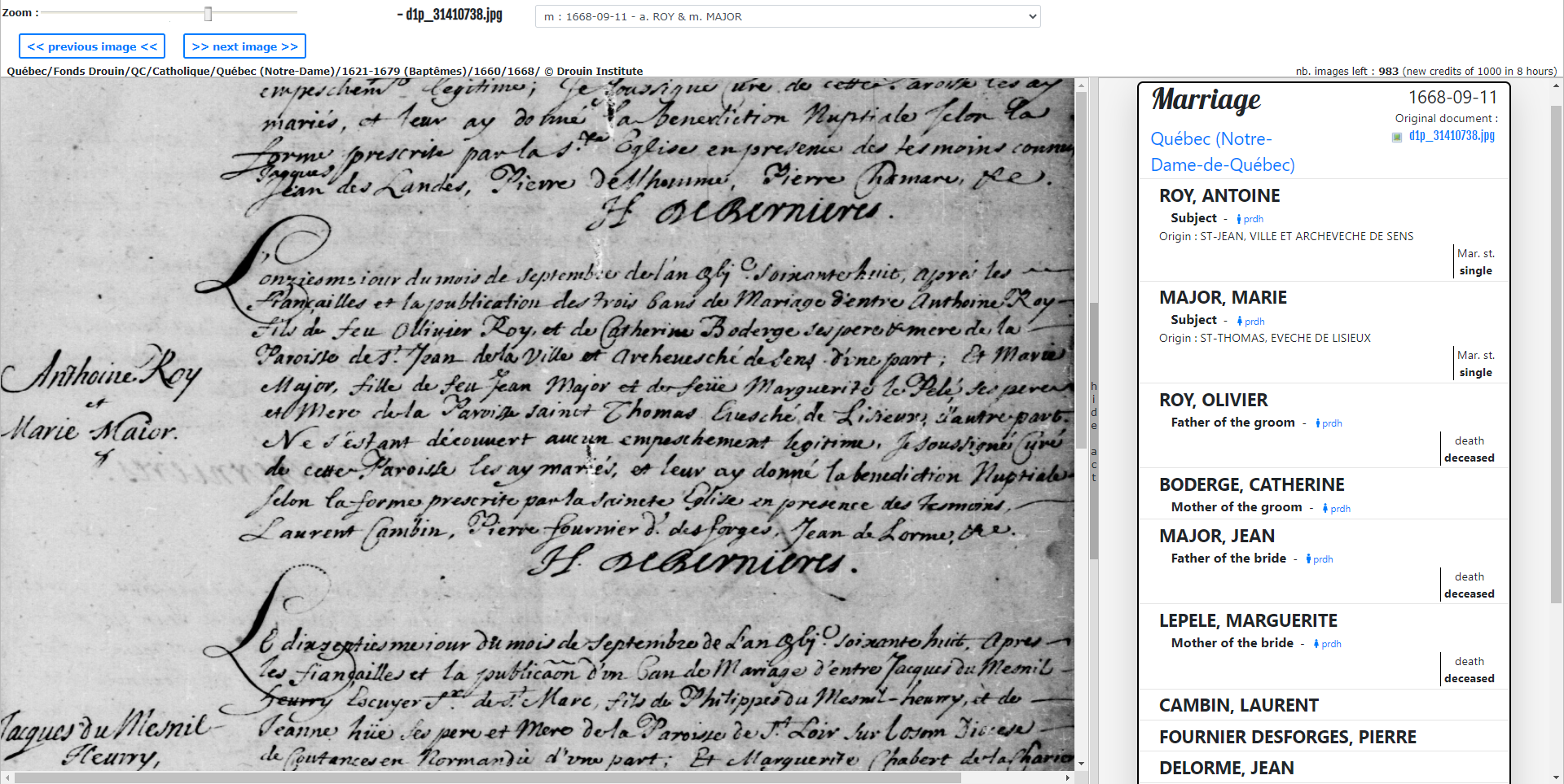

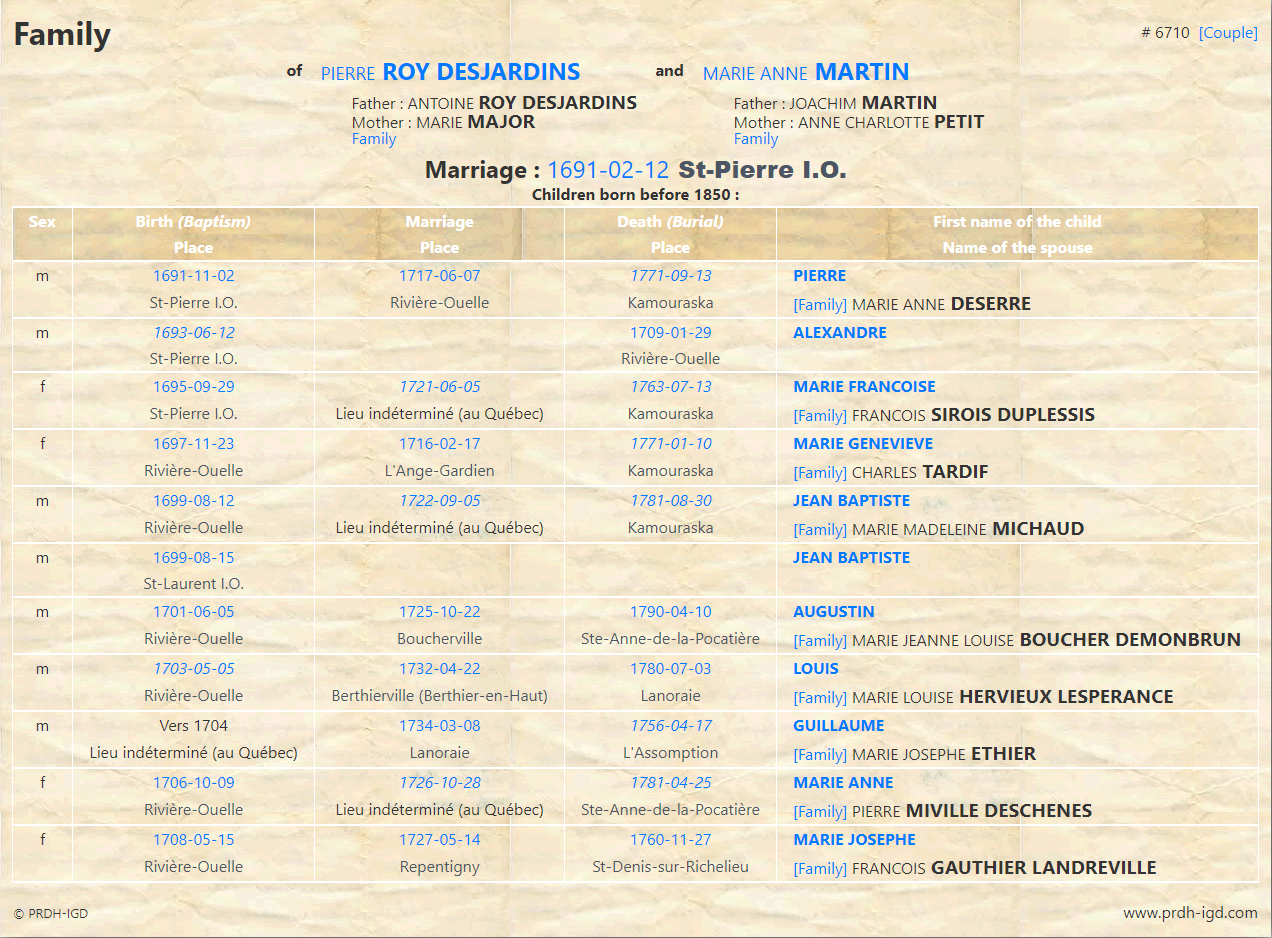

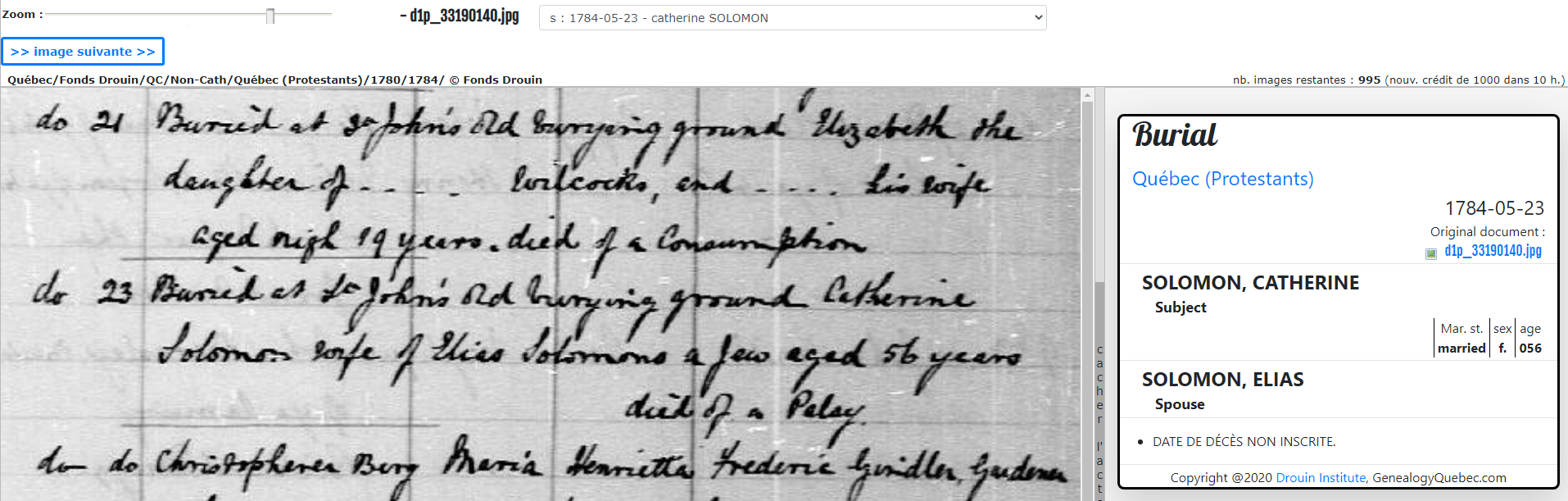

Over the past 20 years, Micromatt has digitized more than 20 million historical records for the Drouin Genealogical Institute, and has developed unparalleled expertise in digitizing historical records of all formats and types.

In addition, Micromatt offers a free optical character recognition (OCR) service, producing a detailed index of scanned documents for you to search.

Digitize twice as many of your historical documents while keeping the same budget!

Thanks to a collaboration with the Drouin Genealogical Institute, you now have the opportunity to double your digitization capacity while keeping the same budget!

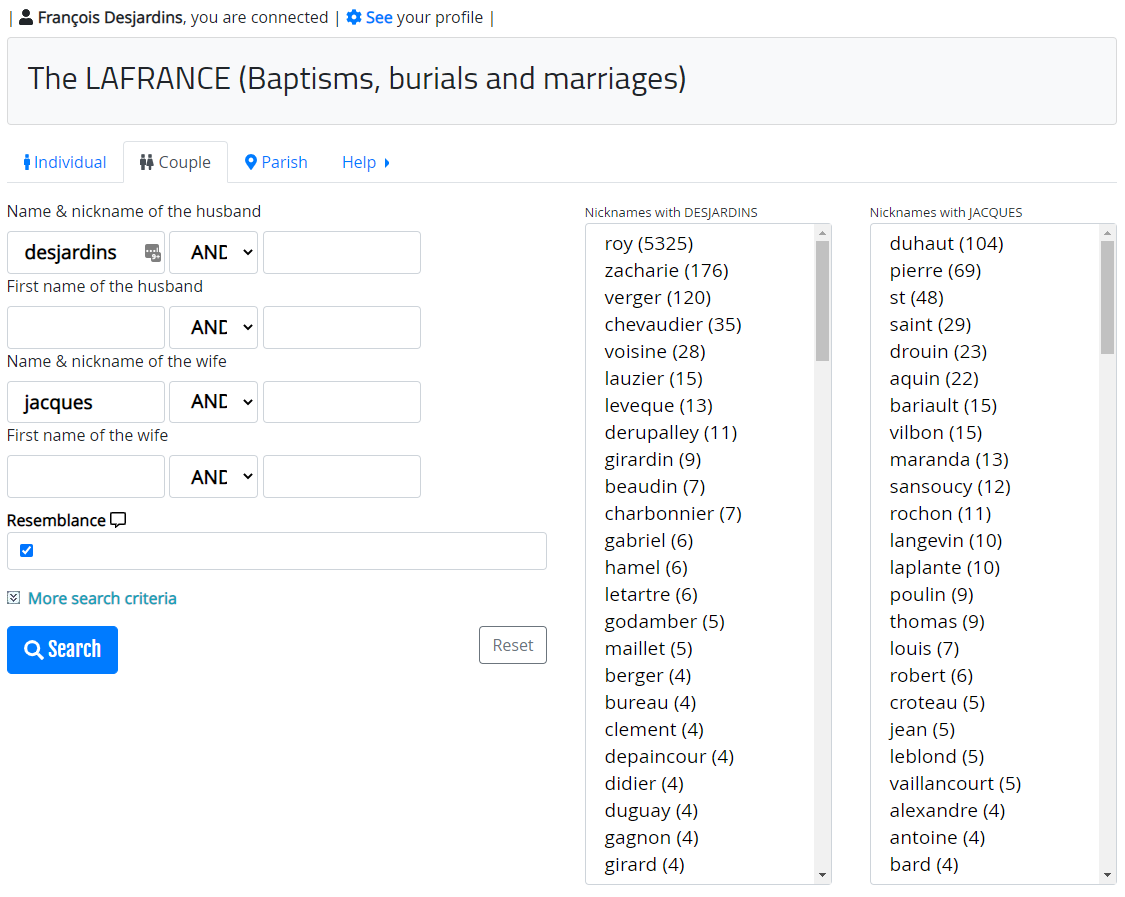

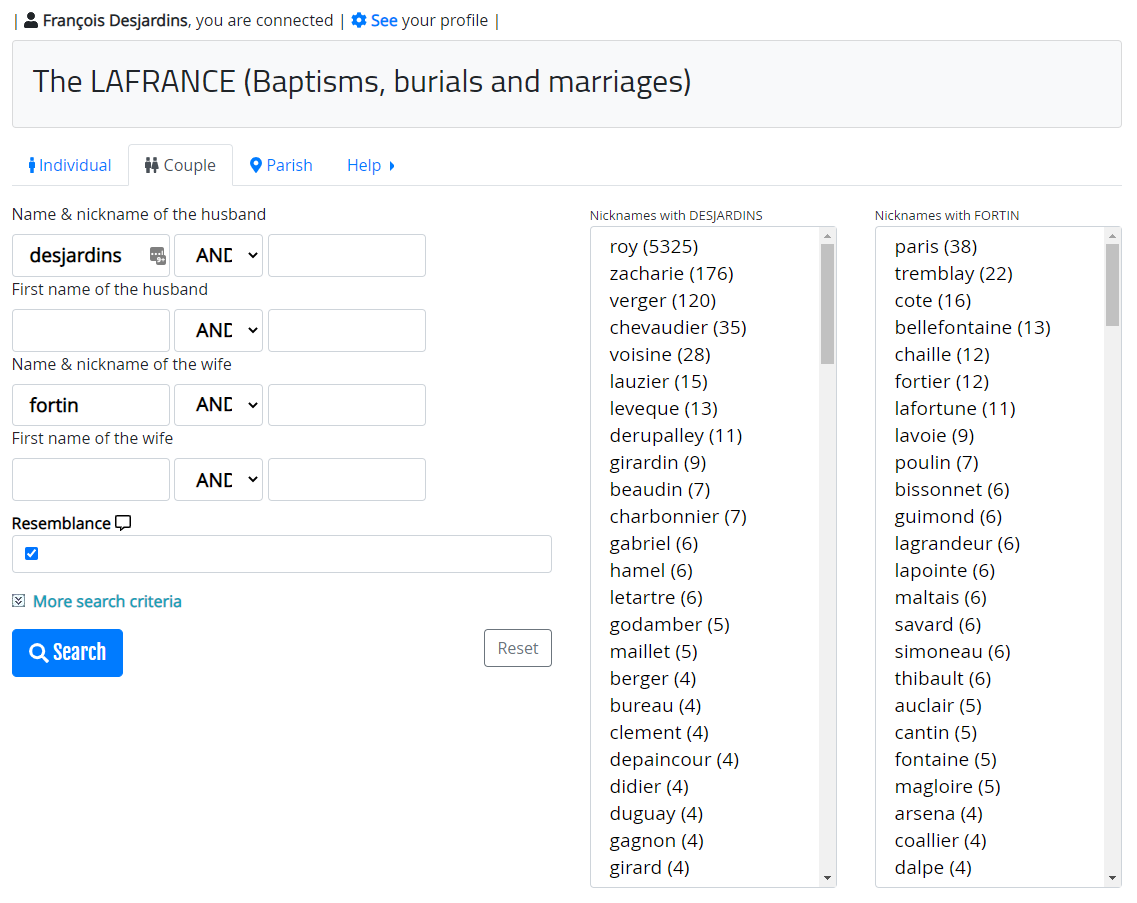

The concept is simple: the Drouin Institute subsidizes 50% of the costs incurred by the digitization of your archives and gives a second life to these documents by making them available on its website GenealogyQuebec.com. The documents digitized on Genealogy Quebec will be used by its members to discover and trace the history of their families in the province.

We are mainly interested in the following types of archives:

- List of electors

- Censuses

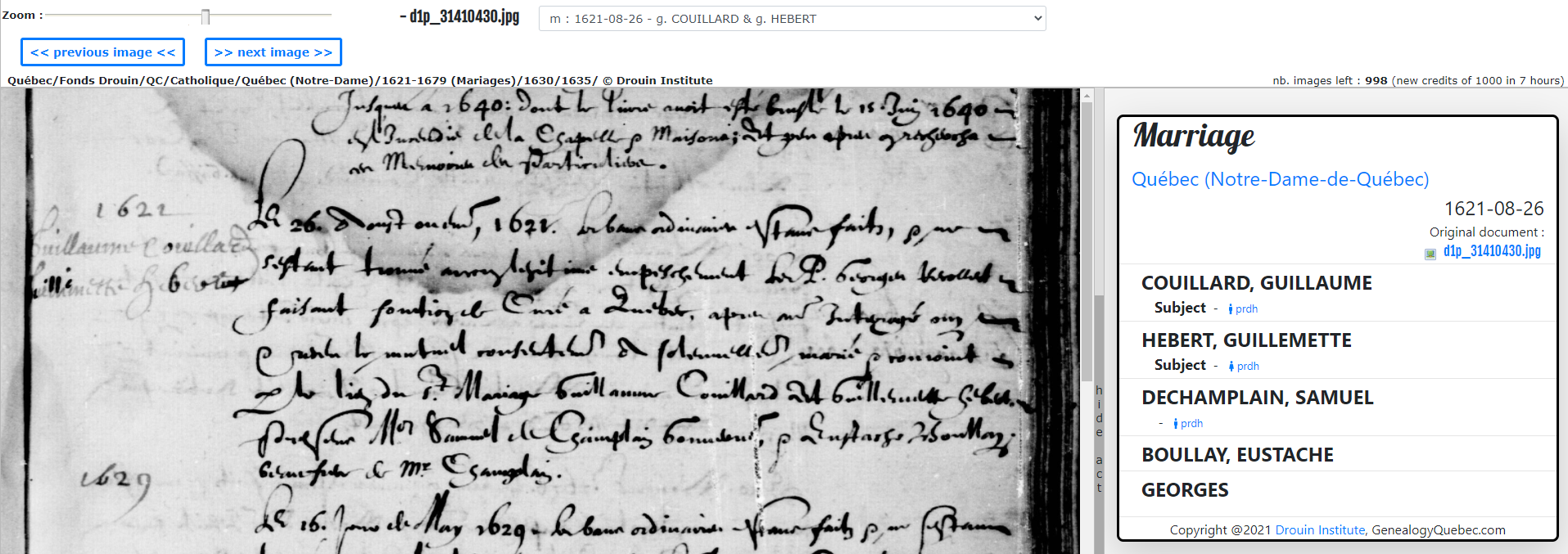

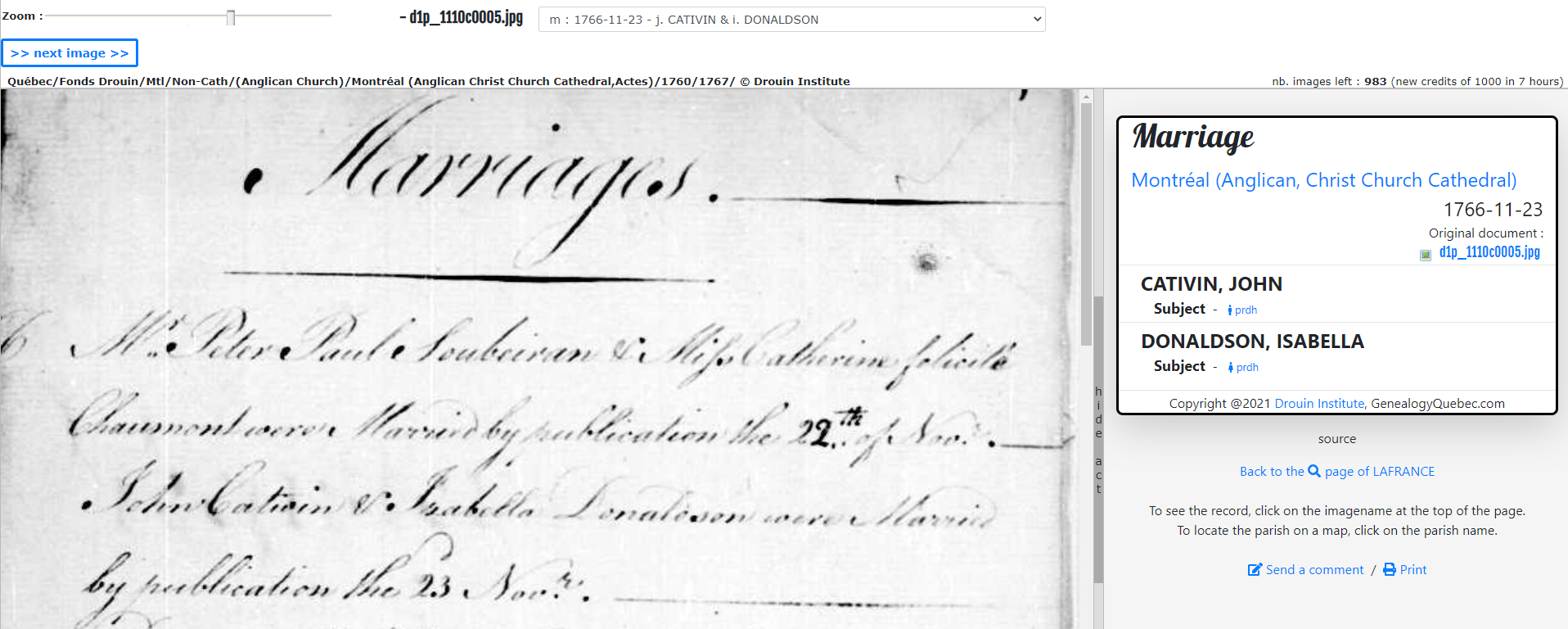

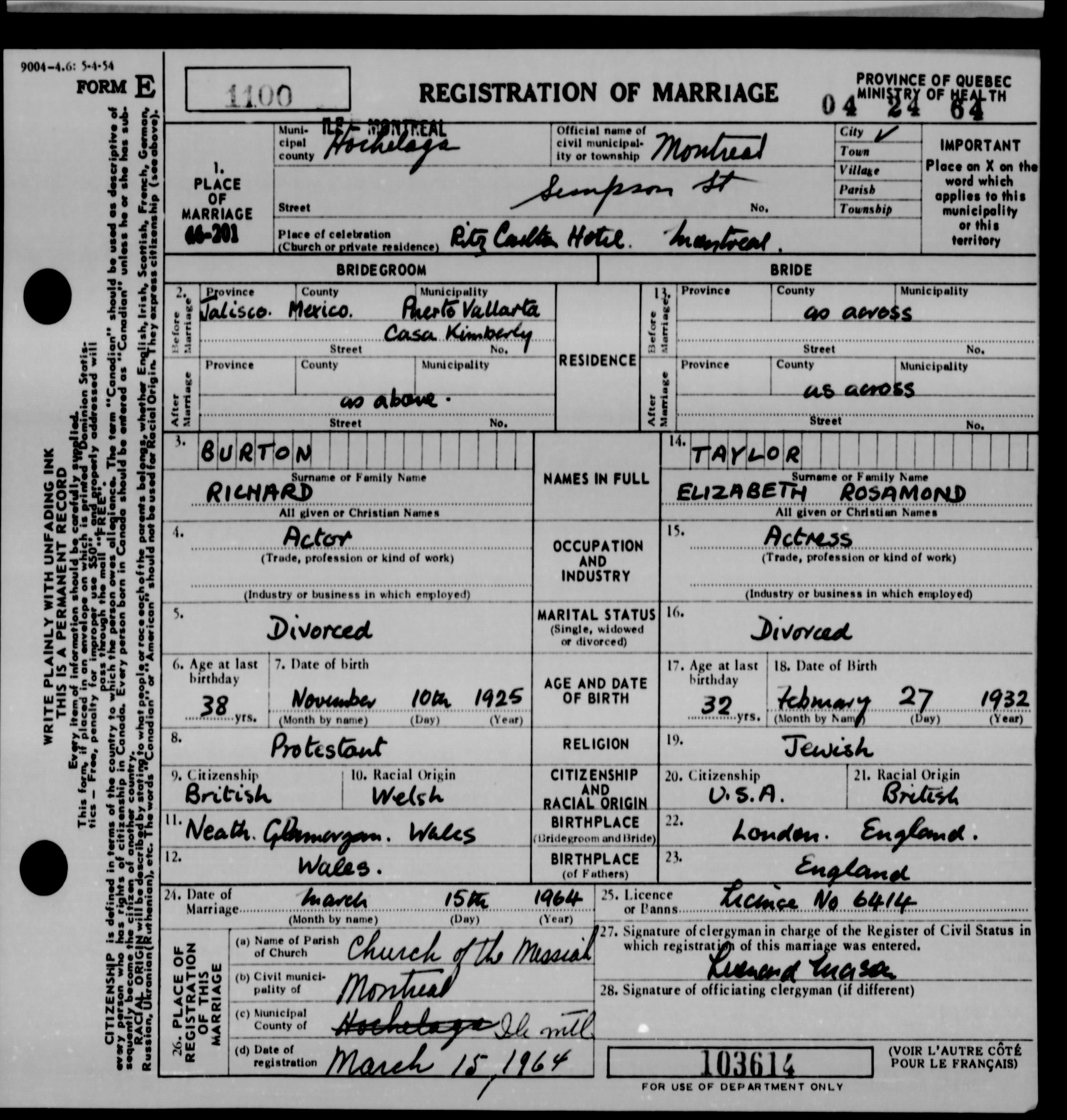

- Birth, marriage and death registers

- Obituaries

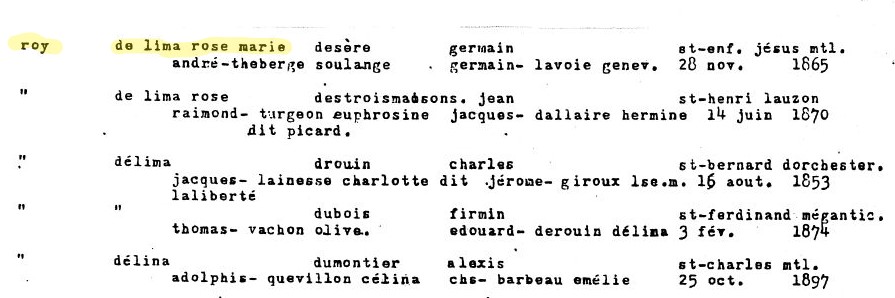

- Baptism, marriage and burial directories

- Headstone pictures

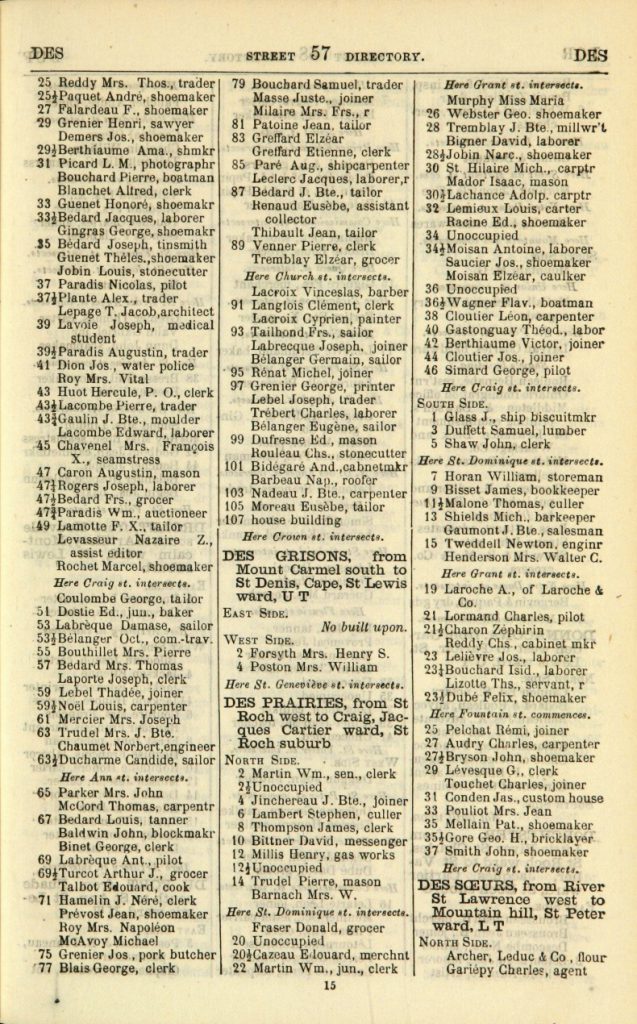

- City directories

- Property assessment rolls (List of land owners)

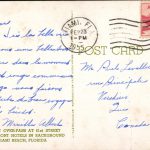

- Memorial cards

- Wedding photos (with names)

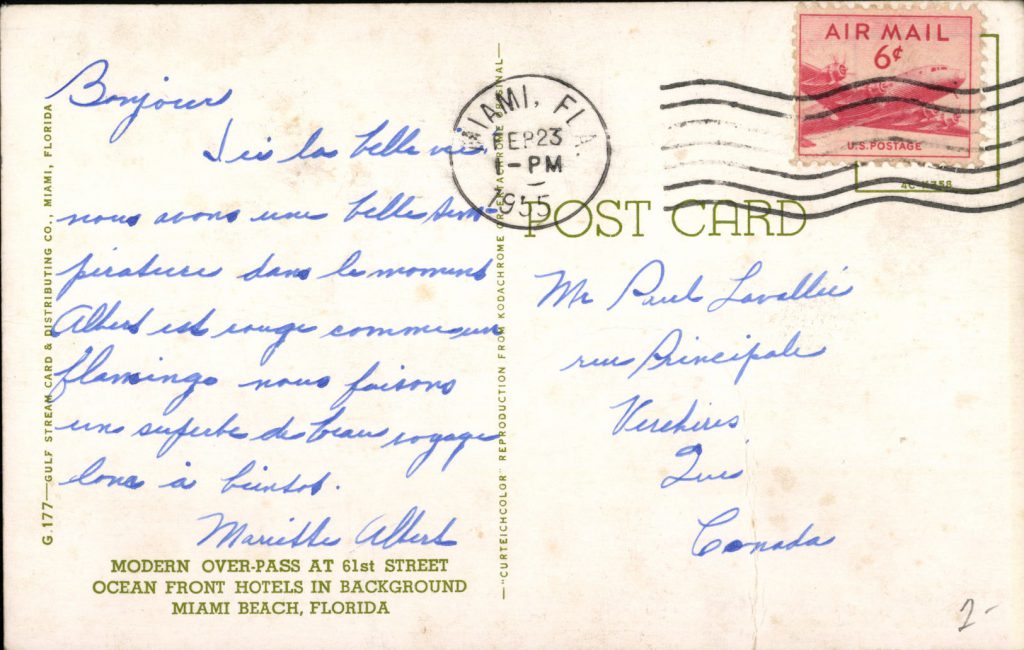

- Postcards

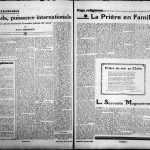

- Newspapers

- School yearbooks

- Boarding school registers (Adoption, nurseries, hospices, orphanages, schools, convents)

- Other historical documents with a high density of names

Contact us to submit your project!

Ready to launch your digitization project or have a question about our services?

Contact us right now!

Phone: (514) 931-7508

Email: micromatt@institutdrouin.com

Address: 1170, rue Beaulac , Saint-Laurent, QC H4R 1R7