(This article is a follow-up to Genealogy and care work)

As genealogists, we have access to little windows into the past. Our familial histories, the lives of our ancestors, all fit into the much larger context of the society in which they lived. If we pay enough attention, we can see traces of that in our research. These little pieces of the past can be very instructive, as they can help us better understand certain realities. In this sense, I believe genealogy can serve feminist emancipation : it can shed light on women’s history.

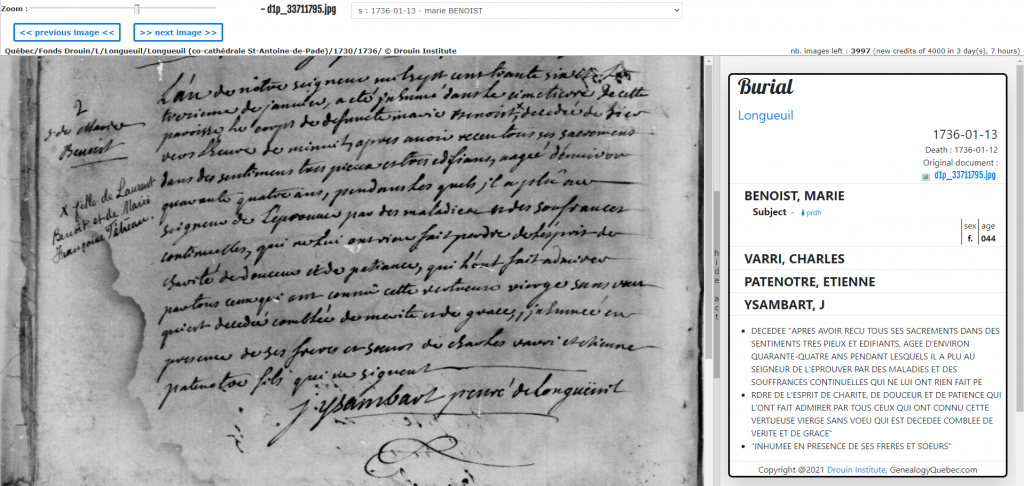

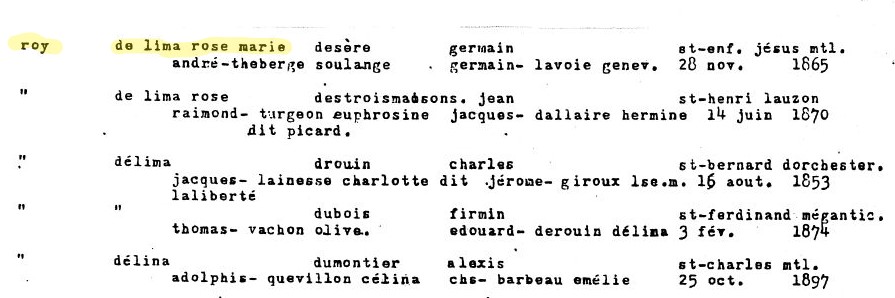

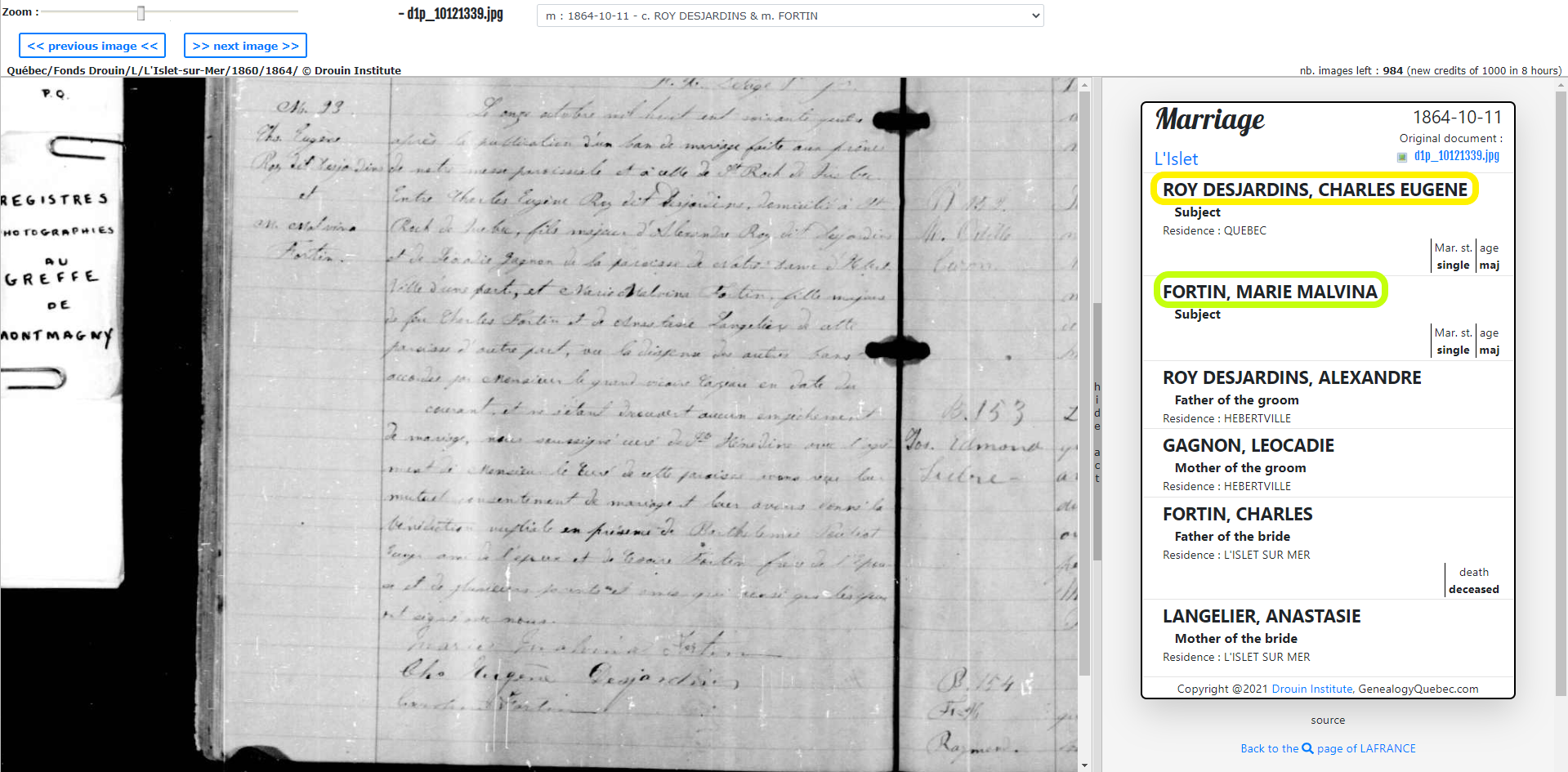

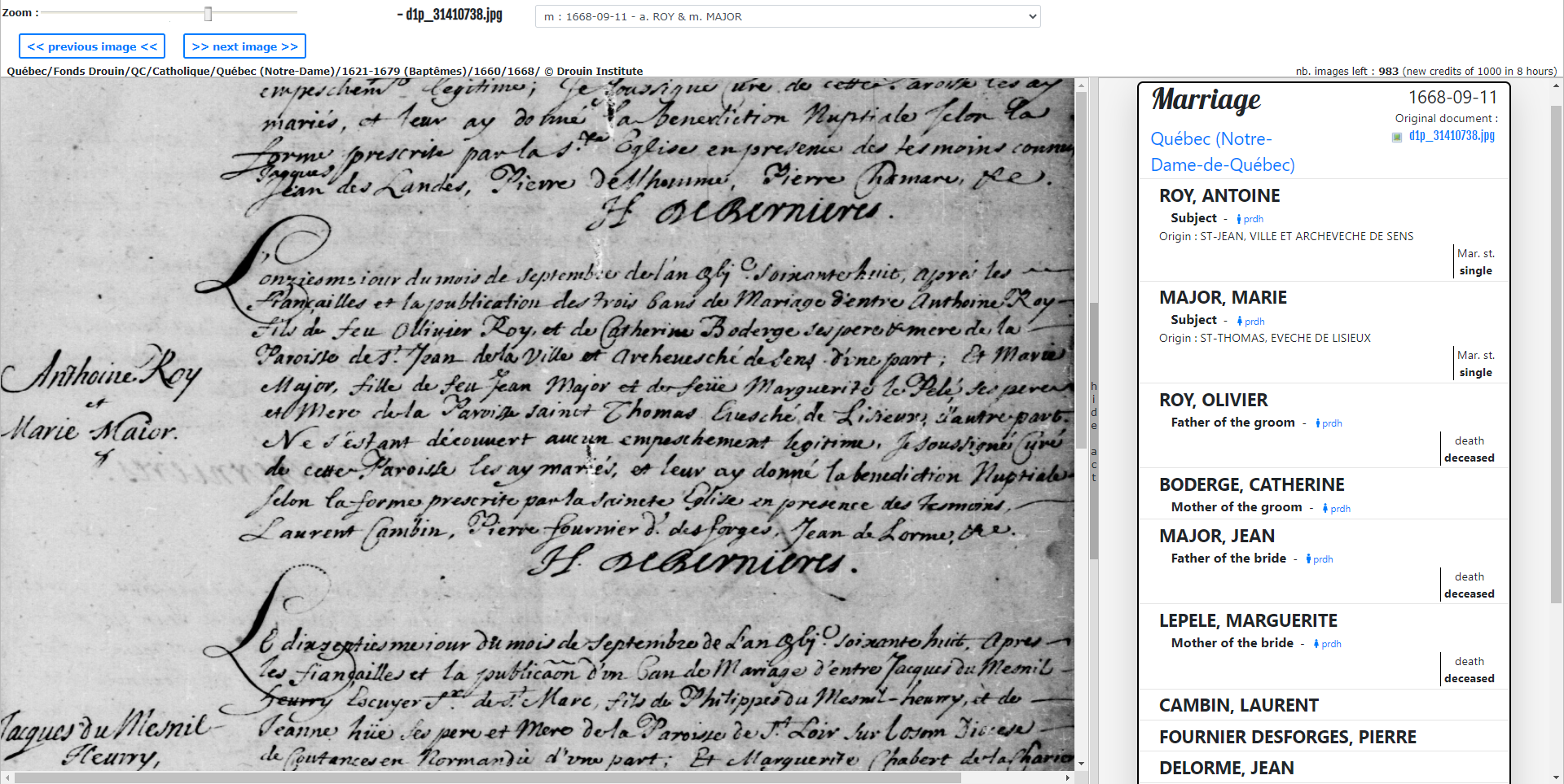

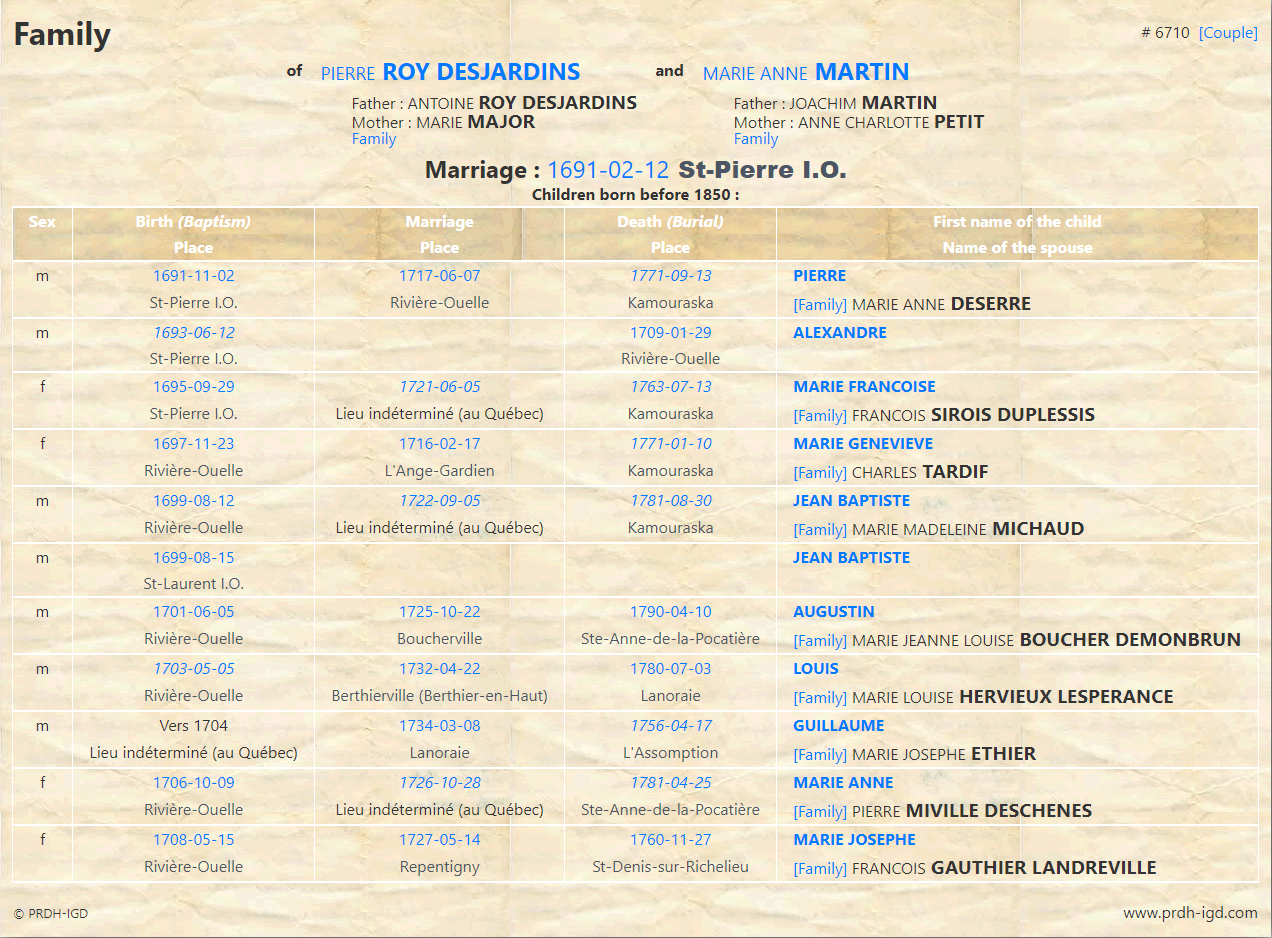

Genealogy can teach us a lot about the living conditions of women at different times. In our genealogical research, we can discover how many children our female ancestors had, at what interval, how many survived, how old they were when they got married and when they gave birth, if they became widows, how many times, at what age, etc. From these facts, we can rebuild their life stories, partially of course, since their lives cannot be summed up entirely to their familial context. However, because the social role of women has often been to take care of their families, these facts can teach us a lot about their daily lives, the major milestones of their lives and the challenges they faced.

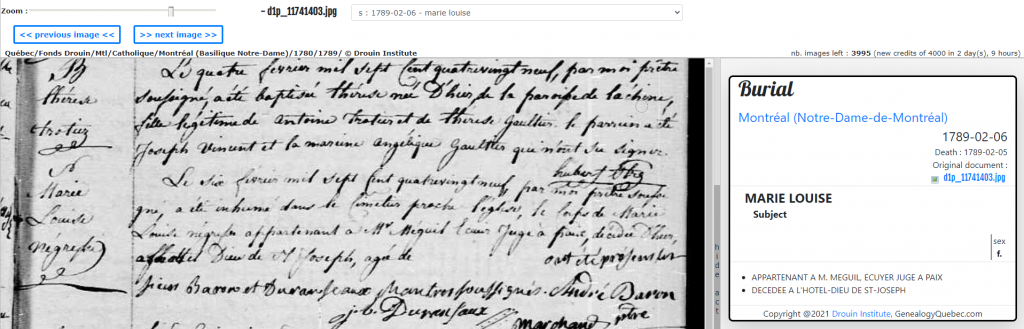

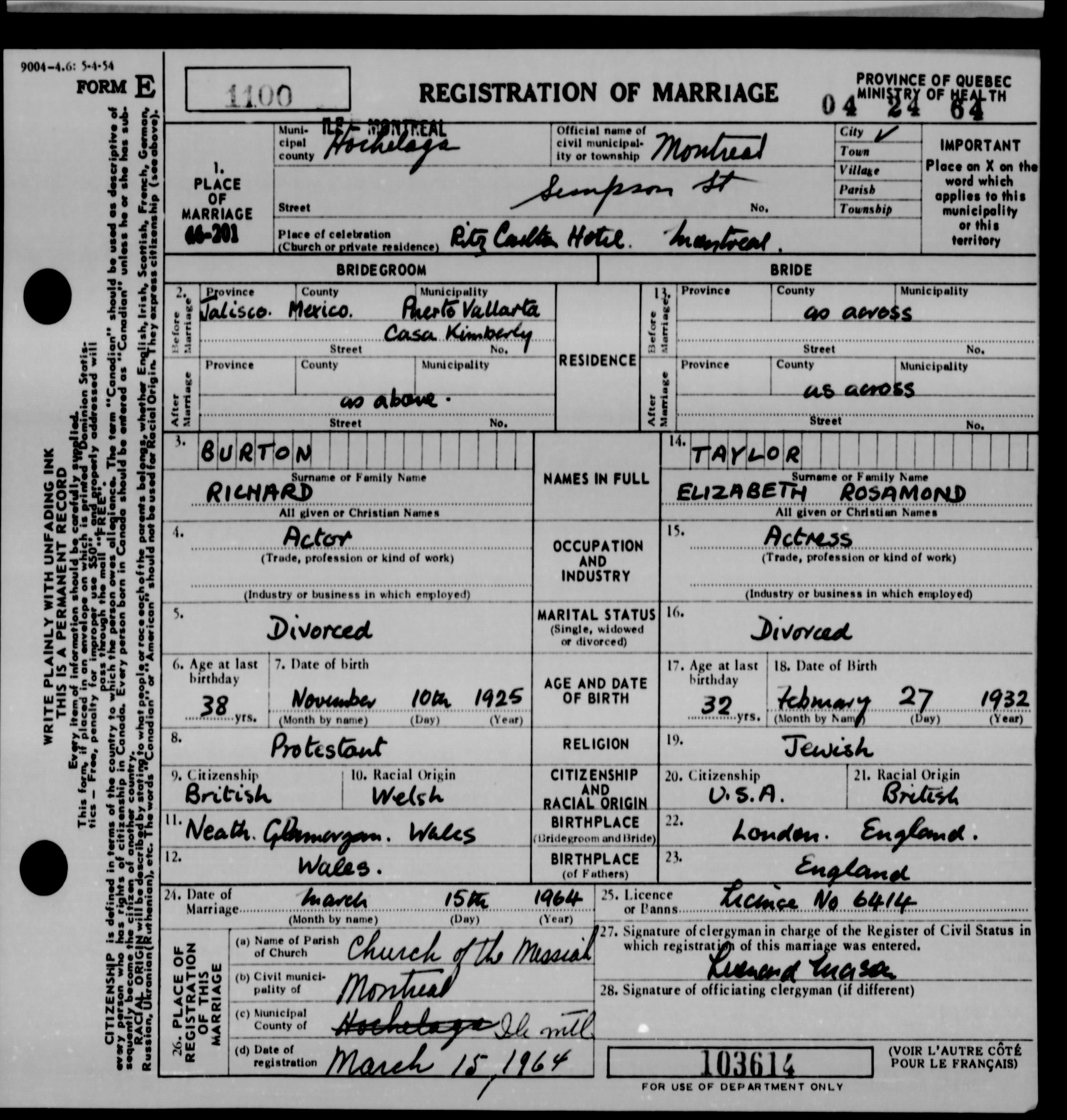

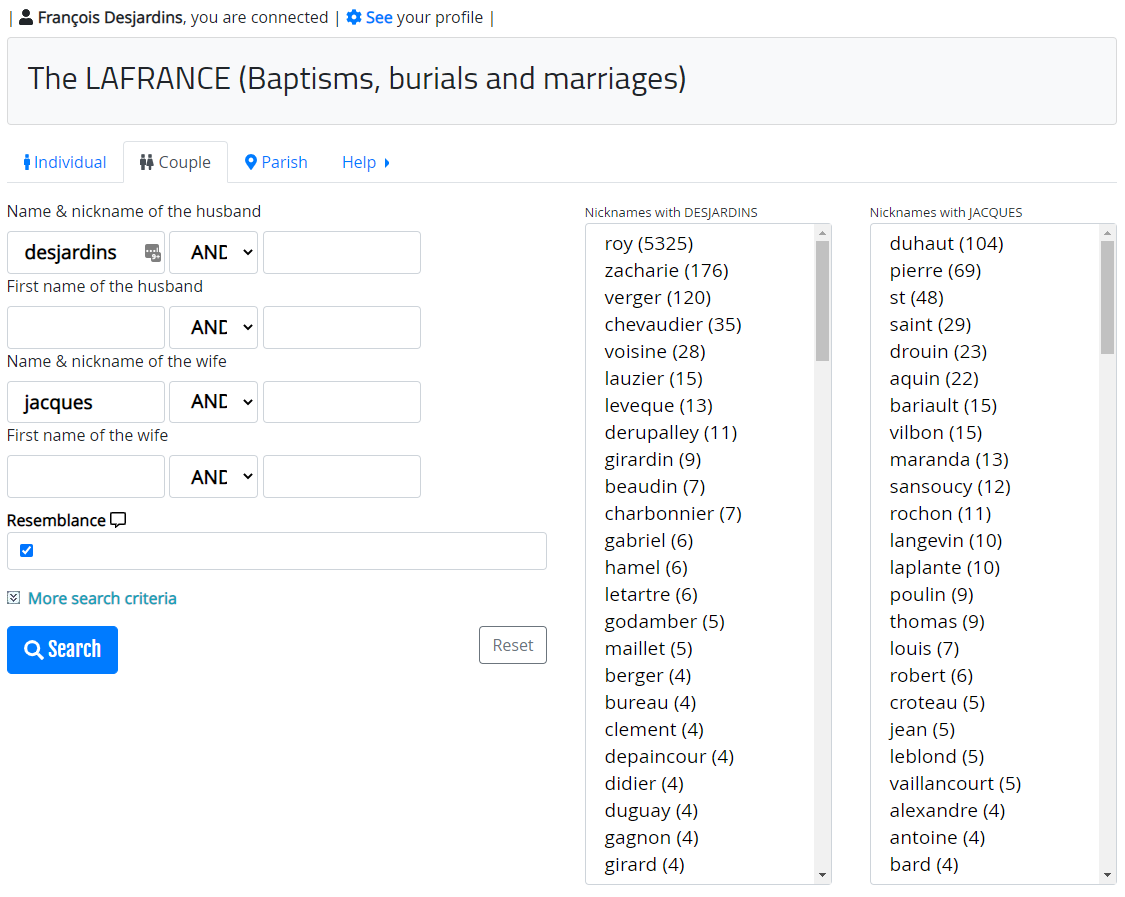

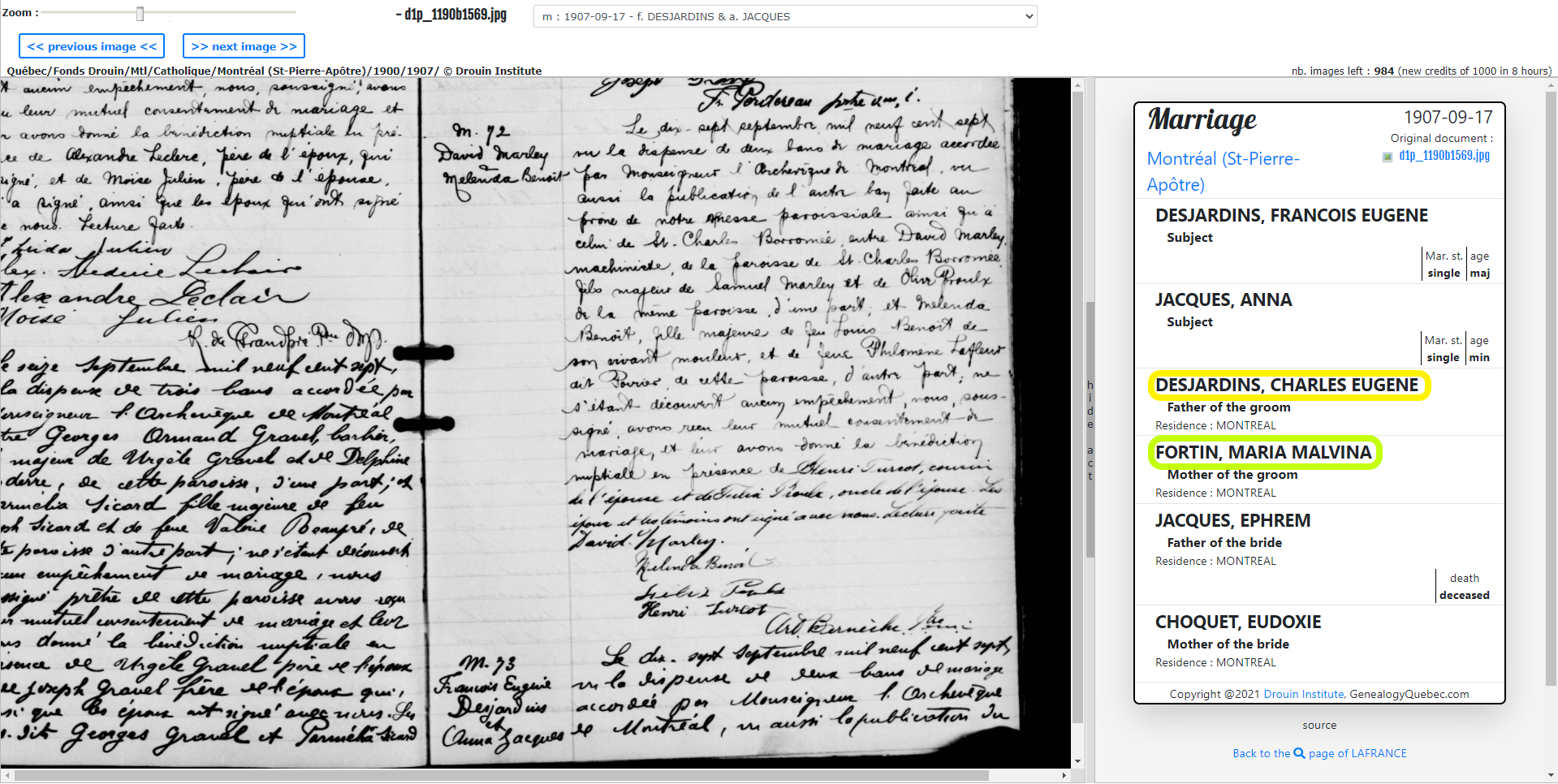

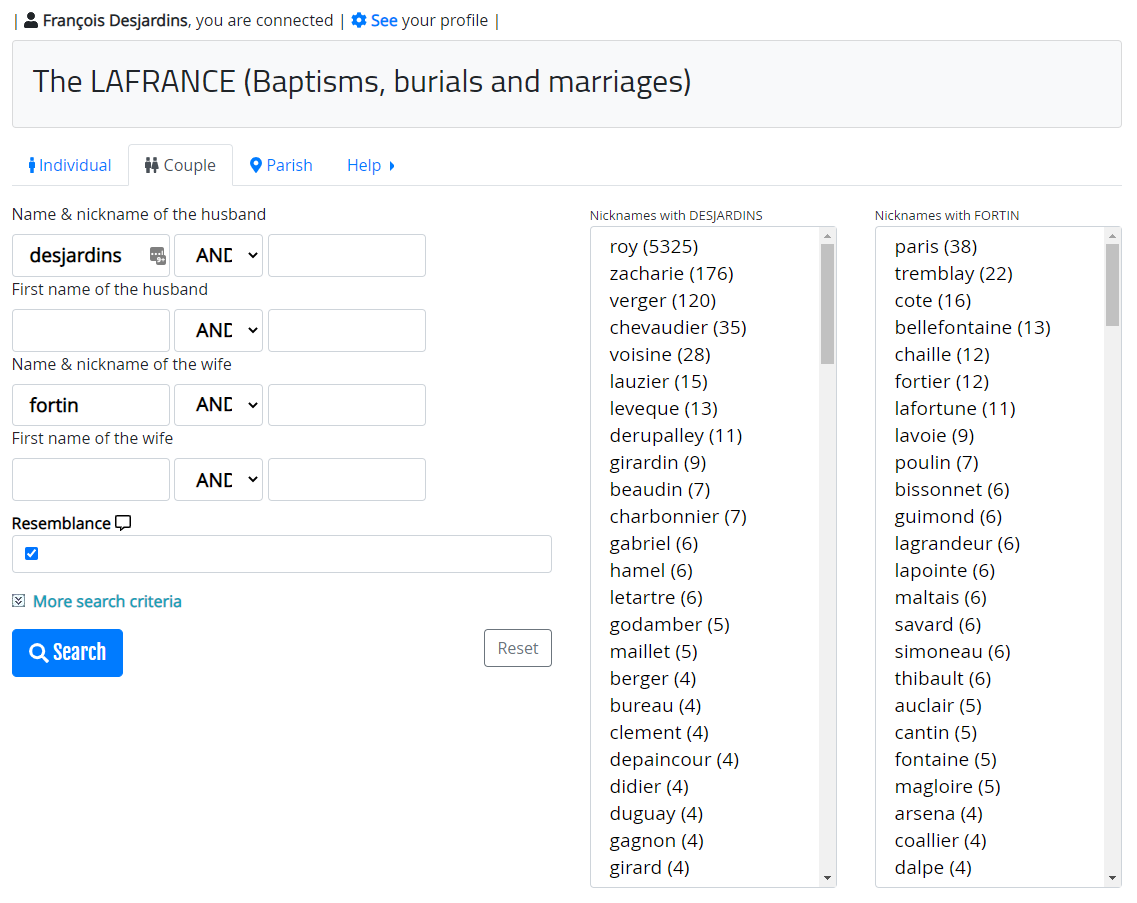

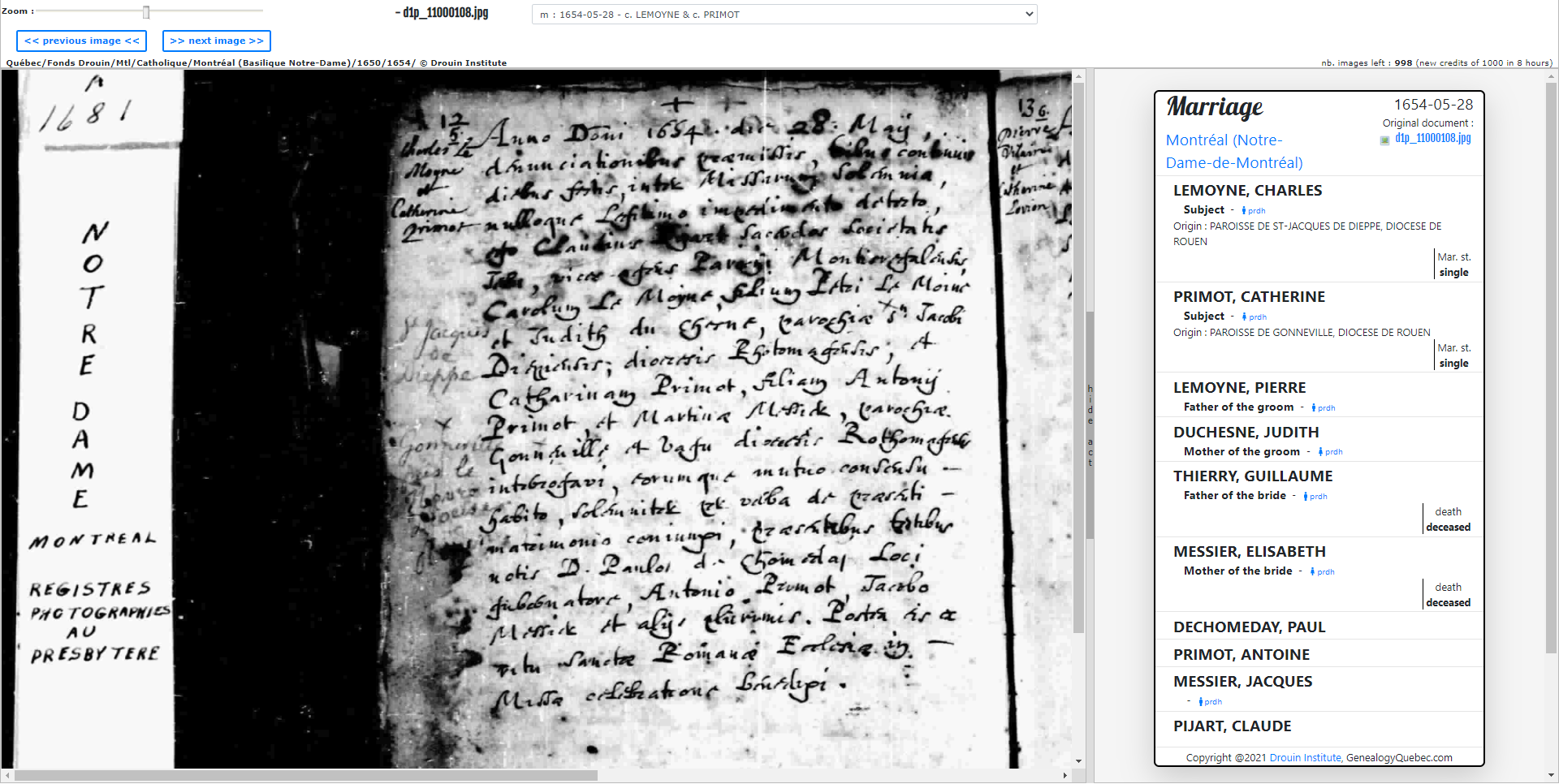

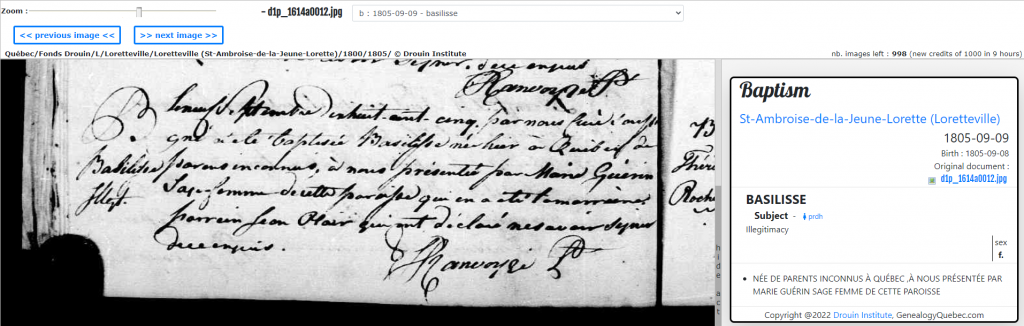

Marie Catherine Sicotte’s individual and family files from PRDH-IGD.com give us a relatively detailed overview of her life; her place and date of birth, marriage and death, the names of her parents as well as the list of her children including the place and date of their birth, marriage and death.

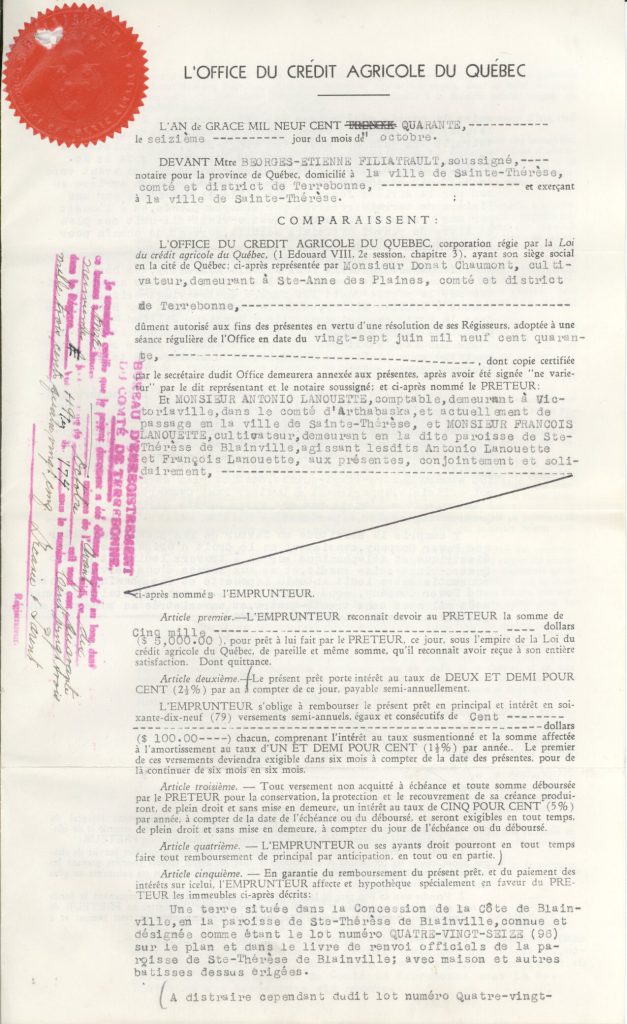

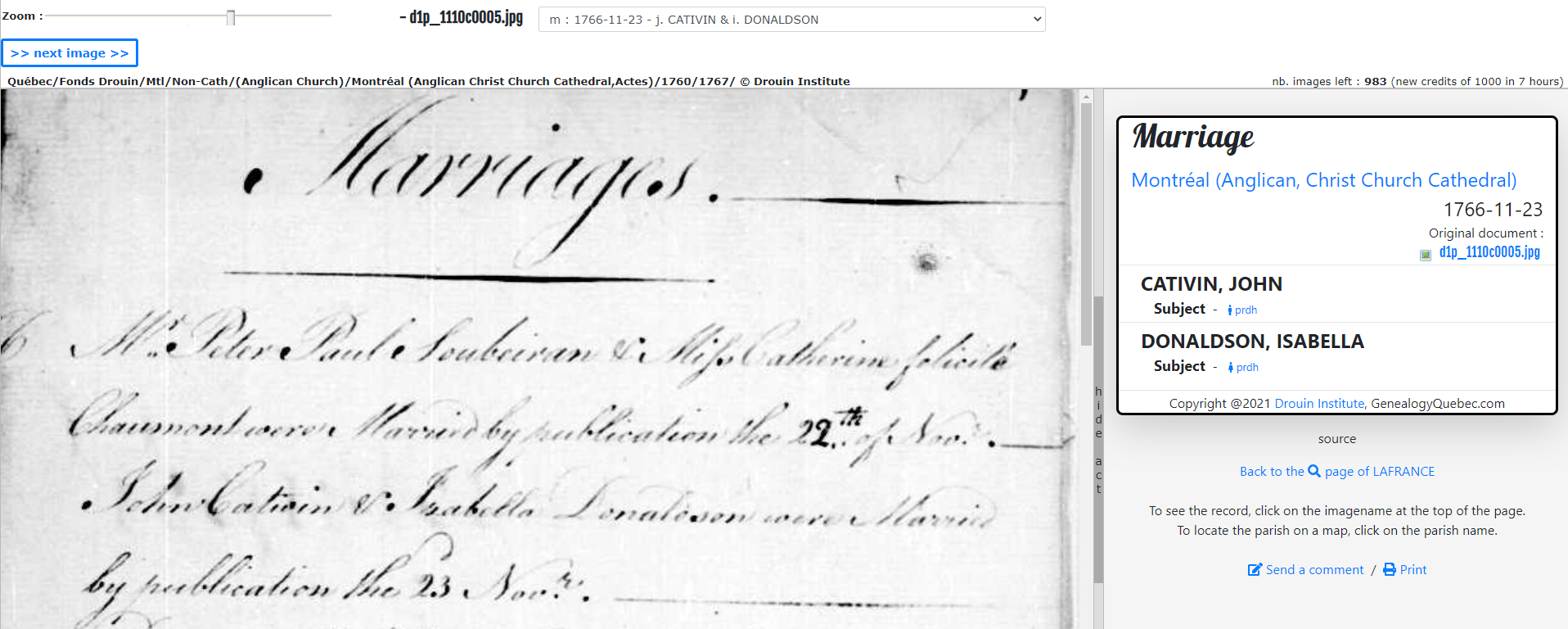

We can also certainly see in this information the different ways in which patriarchy influenced women’s lives. Subtle social norms and very concrete laws concerning the injunction to marriage and motherhood or access to contraception and abortion are directly reflected in our family trees and in our family histories. When we connect the life stories of several generations, we can see how these influences changed over the decades, or even centuries.

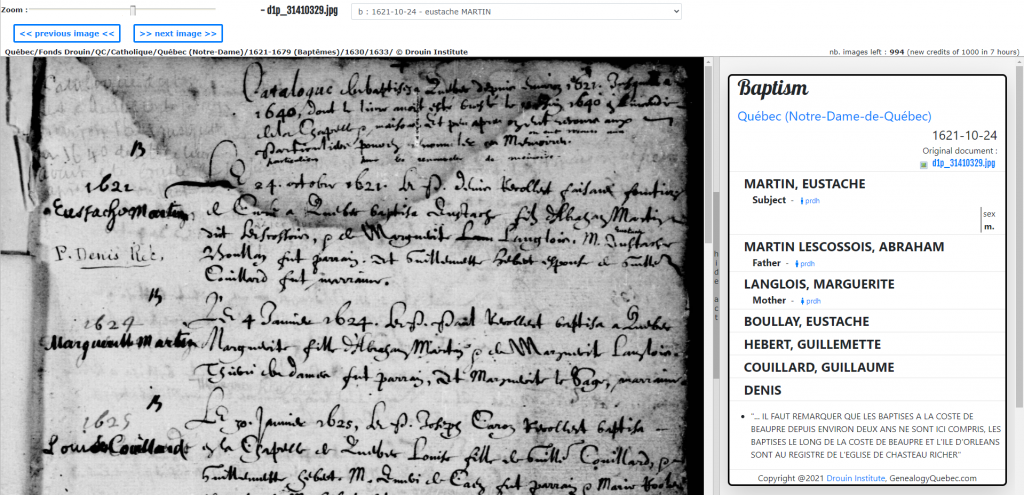

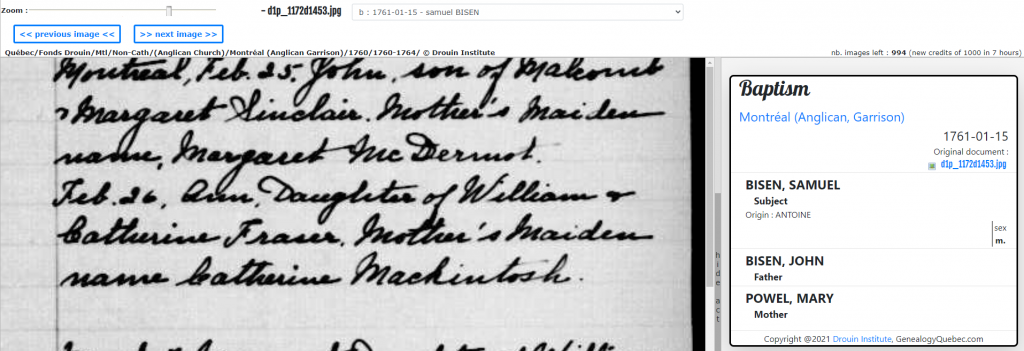

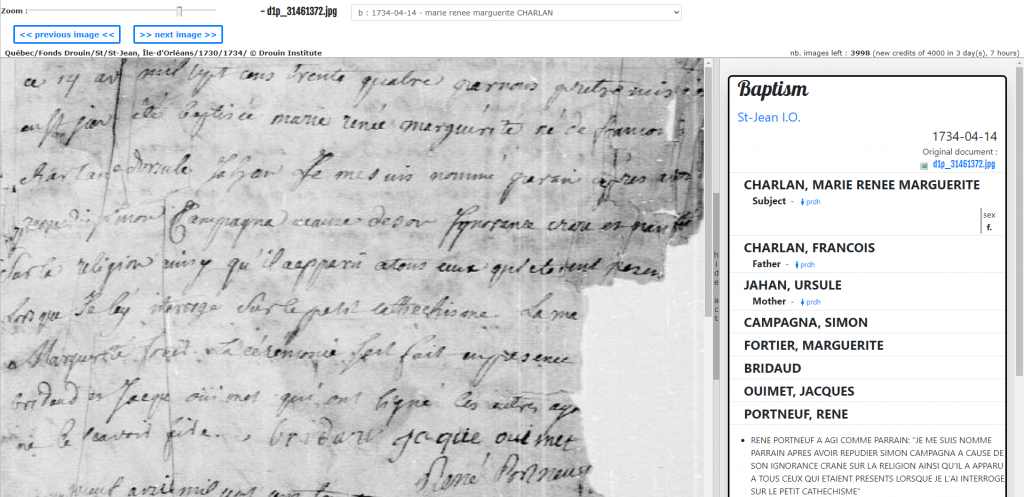

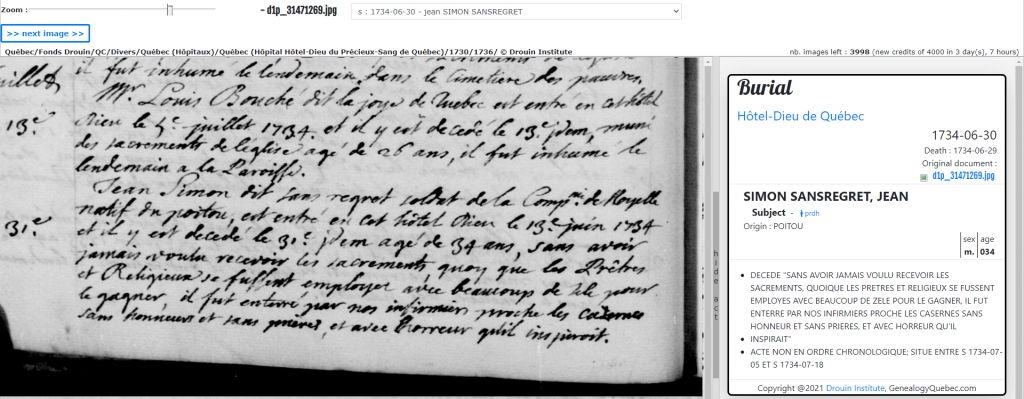

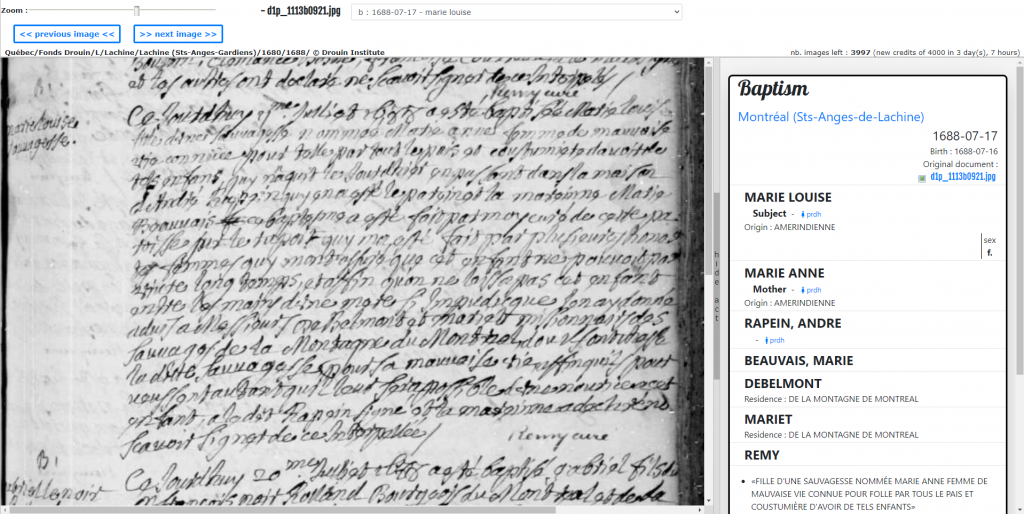

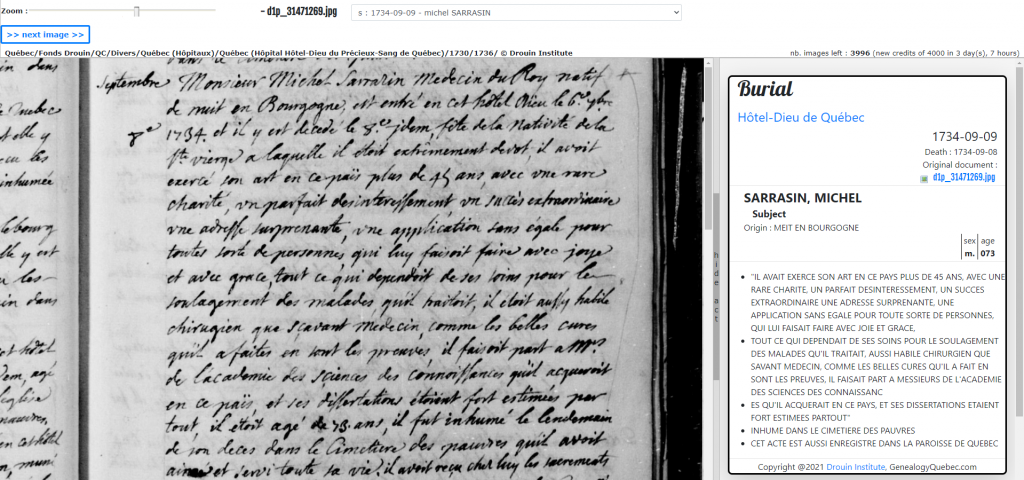

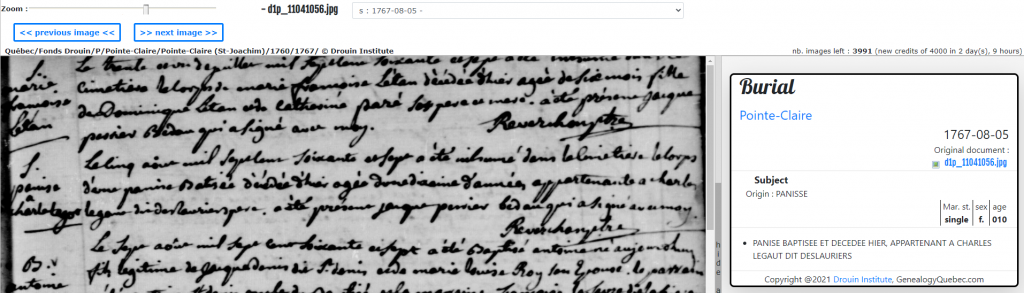

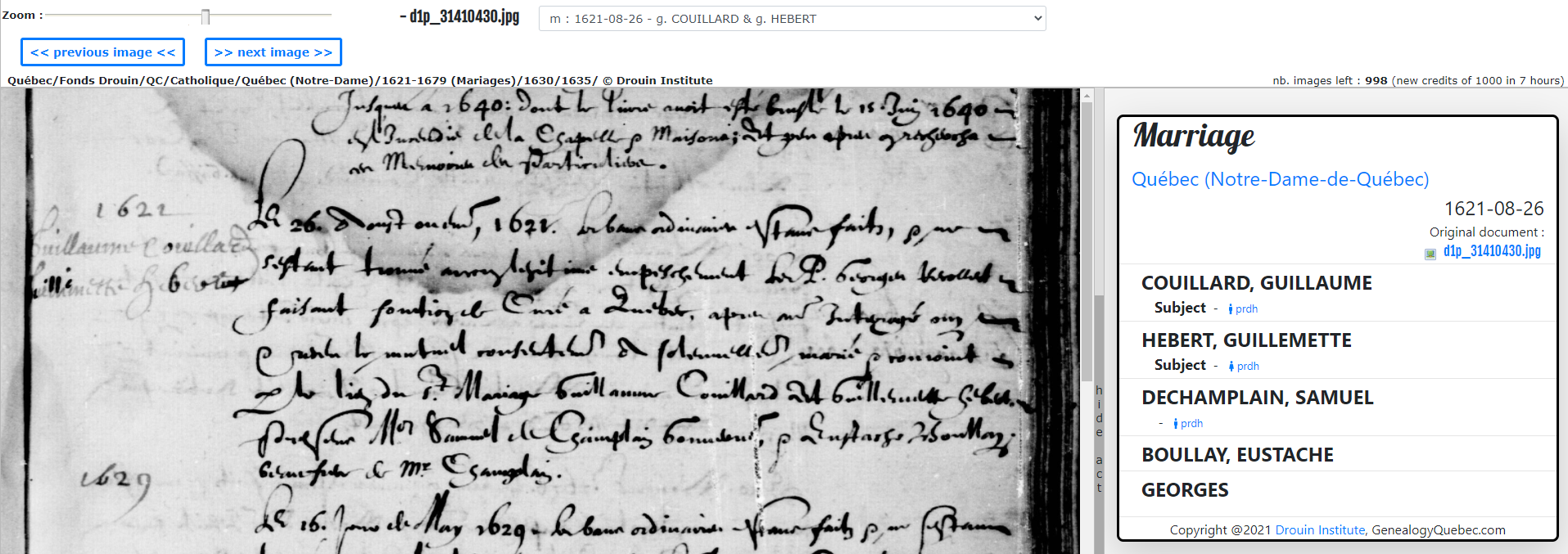

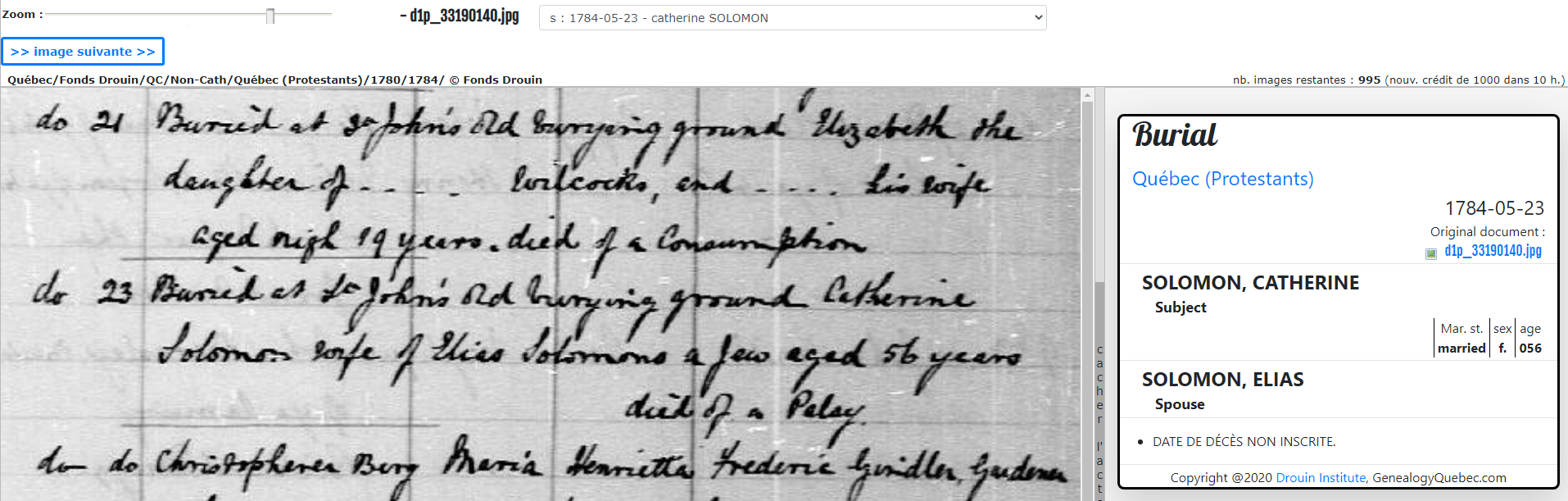

Genealogy can also help us understand what roles women played in society. The documents we use in a genealogical research often mention the men’s occupations, but it’s a lot more rare for women, who were taking care of the children or helping with the family business in the shadows of their husbands. However, there is an exception : the midwives! Midwives who assisted the birth of a child are sometimes mentioned on baptismal records.

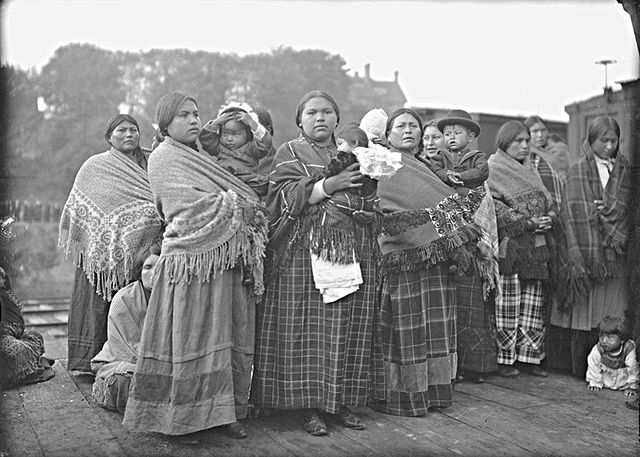

The roles women played in our societies were rarely recognized, let alone valued: and yet, they were crucial. Midwives often were essential local medical resources, especially in smaller or remote villages where access to a doctor was not always guaranteed (Laforce, 1983 :7 ; Bates et al, 2005 :18). House work and child rearing are also essential in any family, and it was often because women took care of it that men were able to devote themselves to more public and supposedly important activities (like politics, art, science, etc).

This devalorization continues to this day : women who choose to be stay-at-home-moms are often seen as ‘’not working’’ (we can think of the notorious play ‘’Môman travaille pas, a trop d’ouvrage’’ (mom doesn’t have a job, she has too much work) (Théâtre des cuisines, 1976)) and jobs typically done by women are significatively underpaid. Canadian Women’s Foundation underlines that ‘’jobs that conform to traditional gender roles tend to be undervalued because they parallel domestic work that women were expected to perform for free’’ (Canadian Women’s Foundation, 2021). By putting these roles forward in our genealogical research, we can participate in their revalorization, so that the contributions of women from the past and the present are more recognized.

This type of genealogical research can also bridge the gap between familial histories, personal to each genealogist, and the much more global history of a society. Genealogy can therefore link the public and private spheres even if they are presented as fundamentally opposed by the patriarchy (Bereni and Revillard, 2009). This opposition is directly linked to women’s oppression : because these spheres are seen as completely different, even incompatible, women’s assignment to the private sphere necessarily excludes them from the public sphere.

Feminists worked towards the deconstruction of this opposition : this idea is notoriously carried in the famous slogan of radical feminists ‘’the personal is political’’. We can therefore consider that particular genealogical practices which link these two spheres and blur the line that divide them participate to this deconstruction and to the feminist emancipation project.

Audrey Pepin

Bibliography

Bates, Christina, Dodd, Diane and Rousseau, Nicole (2005). Sans Frontières : quatre siècles de soins infirmiers canadiens. Ottawa : Les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa. 248 p.

Bereni, Laure and Revillard Anne. (2009). « La dichotomie “Public-Privé’’ à l’épreuve des critiques féministes: de la théorie à l’action publique ». In Genre et action publique : la frontière public-privé en questions, Muller, P. et Sénac-Slawinski, R (dir.). Paris : L’Harmattan. p. 27-55.

Canadian Women’s Foundation (2021). The Facts about the Gender Pay Gap in Canada [Online]. https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/the-gender-pay-gap/

Laforce, Hélène (1983). L’évolution du rôle de la sage-femme dans la région de Québec de 1620 à 1840. (Master’s thesis). Québec : Université Laval, 368 p. https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/28994 Théâtre des cuisines. (1976). Môman travaille pas, a trop d’ouvrage. Montréal : Les Éditions du Remue-Ménage, 78 p.